Roberts J, McNabb K, Bergman A, Taskin T, Mualem B, Ogungbe O. Discontinuation of hormonal contraception: A systemic review and metanalysis. HPHR. 2023;76. https://doi.org/10.54111/0001/XXX2

Around the globe, unintended pregnancy rates remain high, especially among women in low and middle-income countries. A major contributor is contraceptive discontinuation. This study aims to synthesize the rates of early hormonal contraceptive discontinuation (i.e., discontinuation prior to 12 months of use) and the impact of side effects on discontinuation.

A systematic review of seven databases covered articles published between 2011 and 2021. Observational studies that assessed choices about hormonal contraceptive use were included in the final review. As reported in each article reviewed, the pooled proportions of early contraceptive discontinuation rates were calculated using a random effects model. Qualitative and quantitative data about the influence of side effects on discontinuation of hormonal contraception were synthesized using a narrative approach.

Fifty studies met the inclusion criteria. The pooled overall early discontinuation rate was 26% (95% CI: 21–32%). The pooled early discontinuation rates for short-acting hormonal methods like oral contraceptives and injectables were 42% (95% CI: 20–67%) and 21% (95% CI: 7–40%), respectively. Meanwhile, the pooled discontinuation rates for long-acting hormonal methods like implants and intrauterine devices were 22% (95% CI: 16–28%) and 17% (95% CI: 11–24%), respectively. The side effects mentioned most frequently as contributing to hormonal contraceptive discontinuation were abnormal bleeding, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, cramping, headaches, mood changes, and sexual and genitourinary side effects.

High rates of early contraceptive discontinuation persist with varying levels of discontinuation based on contraceptive type. Side effects play a major role in hormonal contraceptive discontinuation. However, there is a dearth of evidence on managing side effects, making this an important area for future research.

Despite the increasing usage of contraceptives among women of reproductive age worldwide, the rate of unintended pregnancies remains high. Between 2015 and 2019, 121 million unintended pregnancies occurred annually, with women in poorer countries accounting for most.1 According to a World Health Organization (WHO) study from 25 countries, method-related concerns, including side effects, are the most common reasons for contraceptive discontinuation.2-4 In fact, about one-third of unintended pregnancies in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) are attributed to contraceptive discontinuation.5

Researchers have identified many reasons for hormonal contraceptive discontinuation based on side effects, including irregular bleeding, amenorrhea, weight gain, pain, and changes to sexual experience.6 There are variations in contraceptive discontinuation by country and method, with shorter-acting methods of birth control (such as oral contraceptive pills and injectables) having higher reported rates of early discontinuation compared to long-acting methods.5,7,8

As the use of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) has gained ground within the past decade,9 it is vital to synthesize existing evidence on specific side effects concerning early discontinuation rates to address the issue of unintended pregnancies. This integrative review of quantitative and qualitative studies is a first step in identifying a baseline framework for analyzing early hormonal contraception discontinuation rates in light of the prevalence of specific side effects.

A systematic literature search was performed in seven databases between January 2011 and August 2021 using keywords and MeSH terms. This search was restricted to the past decade to account for changes in LARC uptake among women after the contraceptive CHOICE project.9 Comprehensive search strategies are in the electronic supplementary material (Appendix A).

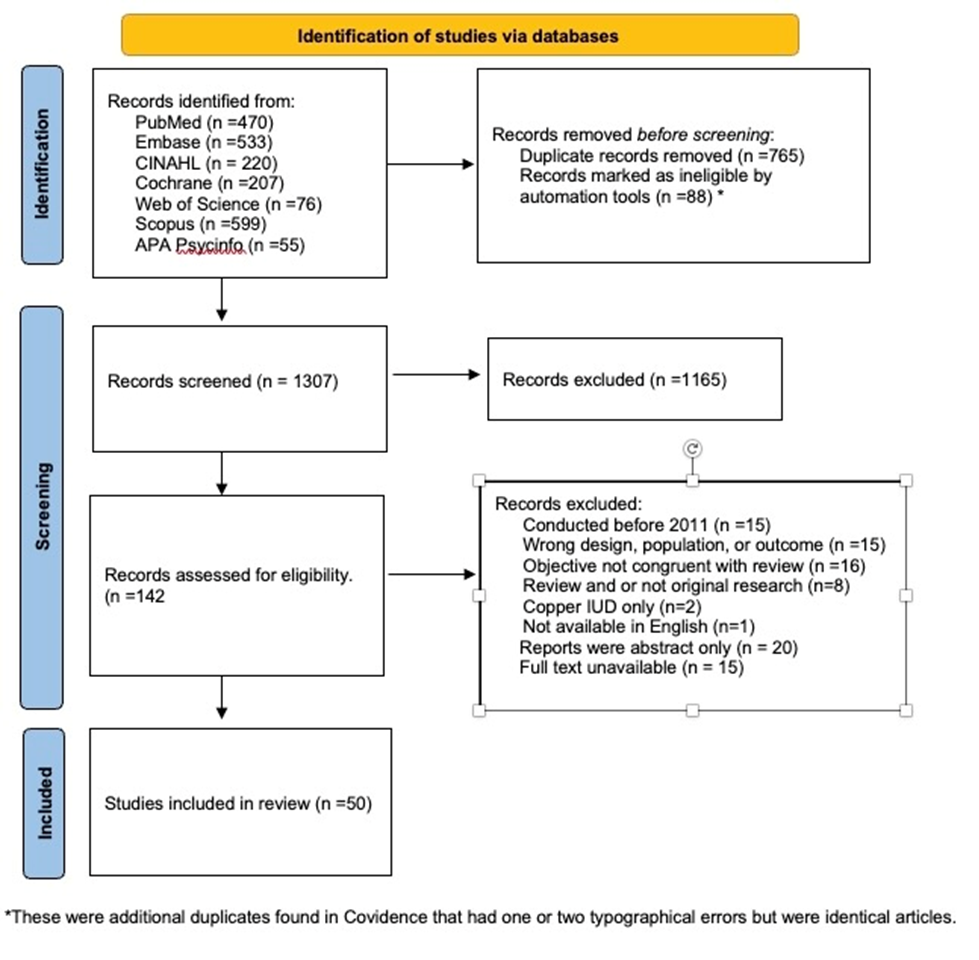

Eligible papers from the seven different electronic database searches were first identified based on the titles of articles that discussed contraceptives, side effects, and/or discontinuation. This yielded 2160 results, of which 853 were duplicates, providing 1307 unique articles. At least two independent reviewers then screened the title and abstract. Studies were eligible if they were peer-reviewed, written in English, and focused on non-randomized observational studies that assessed the choice of hormonal contraceptive use in navigating the competing concerns of side effects and protection. This resulted in another 1165 articles being excluded.

Two reviewers completed an independent full-text review of the remaining 142 articles. During the full-text review, an additional 92 studies were excluded for reasons ranging from being outside the specified time frame to lack of a full-text manuscript or availability in English. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through discussions or the help of an independent third reviewer. Ultimately, 50 full texts were included for review. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA consort diagram.

Figure 1. PRISMA consort diagram.

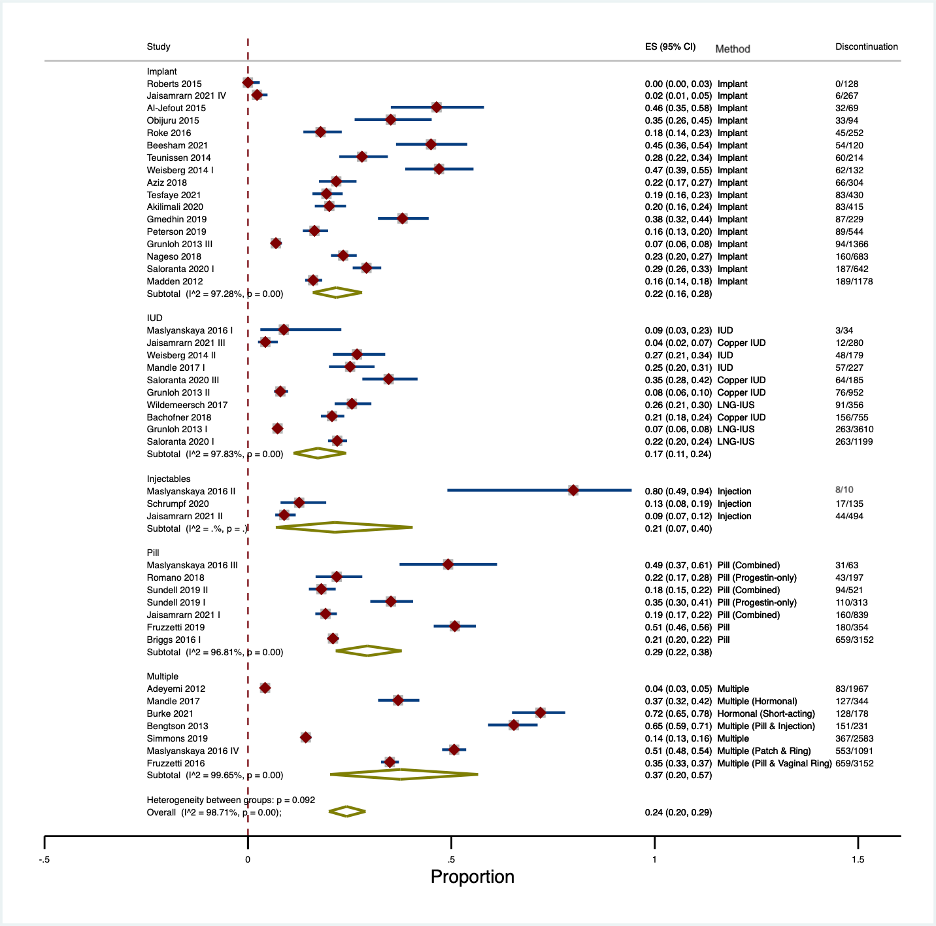

For each eligible article, data extracted included the author and publication year, country, study setting, sample size, disease, population, setting, age of participants, type of contraception, and outcomes reported. Using the “metaprop” package in Stata/IC 16.1, we pooled the proportions of contraceptive discontinuation rates reported in each article using a random effects model.10 We conducted a subgroup analysis by hormonal contraceptive method to generate the pooled estimates. The calculated pooled estimates and exact 95% confidence intervals are displayed in forest plots in Figure 2. Due to the lack of adequate primary quantitative data, data on contraceptive side effects was synthesized using a narrative approach.

Figure 2. Early Discontinuation Rates by Contraceptive Type

The final sample comprised 50 studies. Thirty-seven utilized quantitative research designs, 11 studies employed qualitative designs, and two studies adopted mixed- or multi-method research designs. The quantitative studies encompassed 50,855 women and spanned 22 cohort studies, 14 cross-sectional studies, and one case-control study. Sample sizes in these quantitative studies ranged from 116 to 9,256. Data was collected through questionnaires, structured interviews, and chart reviews. The qualitative studies offered the perspectives of 362 women and gathered data through 286 in-depth interviews and 19 focus groups. Finally, the mixed methods studies collected quantitative data from 281 surveys and qualitative data from 48 in-depth interviews. Most of the data in the included studies were collected between 2006 and 2019. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies, while Appendix D details the aims and themes of the qualitative studies included.

Table 1: Characteristics of Included Studies

First Author & Year | Country | Study Design | Birth Control Methods | Mean Age (SD) | Sample Size | Length of Follow-up (Months) | Parous2 | |||||||

Oral | Implant | Vaginal Ring | Patch | Injection | Hormonal IUD | Copper IUD | Other | |||||||

Romano 2018 | United States | Case-Control | • | 17 (2) | 394 | Varied | Mixed | |||||||

Akilimali 2020 | DRC | Cohort | • | 17.9 (6.3) | 415 | 24 | Mixed | |||||||

Bachofner 2018 | Switzerland | Cohort | • | • | • | 33.4 (6.8) | 755 | 60 | Mixed | |||||

Bengtson 2013 | Uganda & Zimbabwe | Cohort | • | • | NR | 231 | 96 | NR | ||||||

Briggs 2016 | Multi-Site | Cohort | • | NR | 3258 | 12 | NR | |||||||

Burke 2021 | United States | Cohort | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | NR | 1700 | 24 | Yes | |

Diedrich 2015 | United States | Cohort | • | • | • | 25.6 (6.0) | 9256 | 6 | Mixed | |||||

Ferreira 2014 | Brazil | Cohort | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | 35 (0.23) | 1167 | 12 | Mixed |

Fruzzetti 2019 | Italy | Cohort | • | NR (Range:14 – 54) | 354 | 48 | Mixed | |||||||

Grunloh 2013 | United States | Cohort | • | • | • | NR | 6167 | 6 | Mixed | |||||

Jaisamrarn 2021 | Thailand | Cohort | • | • | • | • | NR | 1880 | 12 | Mixed | ||||

Madden 2012 | United States | Cohort | • | • | • | 23.1 (5.6) | 1178 | 36 | Mixed | |||||

Maslyanskaya 2016 | United States | Cohort | • | • | • | • | • | • | 17.7 (1.8) | 145 | 6 | Mixed | ||

Obijuru 2015 | United States | Cohort | • | • | 17 (1.8) | 116 | 36 | Mixed | ||||||

Peterson 2019 | United States | Cohort | • | 23.7 (5.8) | 544 | 12 | Mixed | |||||||

Roke 2016 | New Zealand | Cohort | • | 24.5 (Range:13 – 50) | 252 | 12 | NR | |||||||

Saloranta 2020 | Finland | Cohort | • | • | • | 28.6 (IQR: 23.1 – 33.4) | 2026 | 24 | Mixed | |||||

Simmons 2019 | United States | Cohort | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | NR | 3688 | 24 | Mixed | |

Sundell 2019 | Sweden | Cohort | • | • | 29 (Range:18 – 40) | 1115 | 60 | NR | ||||||

Teunissen 2014 | Netherlands | Cohort | • | 26.9 (7.6) | 214 | 36 | Mixed | |||||||

Vickery 2013 | United States | Cohort | • | • | • | NR | 427 | 12 | Mixed | |||||

Weisberg 2014 | Australia | Cohort | • | • | NR | 311 | 36 | Mixed | ||||||

Wildemeersch 2017 | Belgium | Cohort | • | • | 35.1 (8.8) | 356 | 120 | Mixed | ||||||

Adeyemi 2012 | Nigeria | Cross-Sectional | • | 34.04 (5.68) | 433 | n/a | Yes | |||||||

Al-Jefout 2015 | Jordan | Cross-Sectional | • | 30.9 (4.9) | 69 | n/a | Yes | |||||||

Beesham 2021 | South Africa | Cross-Sectional | • | 27 (IQR: 24 – 32) | 120 | n/a | NR | |||||||

Fruzzetti 2016 | Italy | Cross-Sectional | • | • | • | NR (Range:14 – 42) | 1809 | n/a | Mixed | |||||

Gmedhin 2019 | Ethiopia | Cross-Sectional | • | 261 (Range:16 – 51) | 229 | n/a | Yes | |||||||

Hirth 2021 | United States | Cross-Sectional | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | NR | 2632 | n/a | Mixed |

Hladky 2011 | United States | Cross-Sectional | • | • | 31.9 (0.3) | 1,665 | n/a | Mixed | ||||||

Johnson 2013 | Multi-Site | Cross-Sectional | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | 35 | 2544 | n/a | NR |

Madden 2015 | United States | Cross-Sectional | • | • | • | • | • | • | 25.6 (5.9) | 2590 | n/a | Mixed | ||

Mandle 2017 | Multi-Site | Cross-Sectional | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | NR | 1144 | n/a | NR |

Martin 2018 | NR | Cross-Sectional | • | • | • | • | • | • | 24.2 (4.4) | 430 | n/a | NR | ||

Nageso 2018 | Ethiopia | Cross-Sectional | • | 24.5 (4.8) | 683 | n/a | Mixed | |||||||

Roberts 2015 | Nigeria | Cross-Sectional | • | 33.6 (2.4) | 128 | n/a | Mixed | |||||||

Tesfaye 2021 | Ethiopia | Cross-Sectional | • | 25.7 (5.1) | 430 | n/a | Yes | |||||||

Dasari 2016 | United States | Mixed Methods | • | • | • | • | • | 21 | 15 | n/a | Mixed | |||

Schrumpf 2020 | Ghana | Mixed Methods | • | • | • | • | 29.4 (7.8) | 135 | n/a | Mixed | ||||

Alspaugh 2021 | United States | Qualitative | 45.1 (Range: 40 – 55) | 20 | n/a | NR | ||||||||

Austad 2020 | Guatemala | Qualitative | • | • | • | • | • | 29.8 (Range: 21 – 42) | 24 | n/a | Yes | |||

Berndt 2021 | United States | Qualitative | 30 (Range: 16 – 44) | 86 | n/a | Mixed | ||||||||

Dolan 2021 | Australia | Qualitative | • | • | NR | 22 | n/a | Mixed | ||||||

Flore 2016 | Australia | Qualitative | • | 24.5 (Range: 18 – 39) | 18 | n /a | Mixed | |||||||

Higgins 2015 | United States | Qualitative | • | • | • | NR | 52 | n/a | NR | |||||

Hoggart 2013a | United Kingdom | Qualitative | • | NR (Range: 16 – 22) | 20 | n/a | NR | |||||||

Hoggart 2013b | United Kingdom | Qualitative | • | NR (Range: 16 – 22) | 20 | n/a | NR | |||||||

Kelly 2019 | United States | Qualitative | • | • | • | 17 (Range: 15 – 19) | 21 | n/a | NR | |||||

Sarfraz 2021 | Pakistan | Qualitative | • | • | • | NR (Range: 20 – 33) | 27 | n/a | Yes | |||||

Schmidt 2015 | United States | Qualitative | • | • | 18 (1.4) | 43 | n/a | Mixed | ||||||

The largest proportion of studies was conducted in the WHO’s Region of the Americas (21). In contrast, the remaining studies were distributed across the Europe Region (9), the African Region (8), the Western Pacific Region (4), the Eastern Mediterranean Region (3), and the South-East Asian Region (1). Four studies were conducted at multiple sites.

The objectives of the studies were categorized into three main types: studies investigating the reasons for or factors associated with contraceptive choice and initiation; studies exploring the rates of, reasons for, and factors associated with contraceptive continuation or discontinuation; and studies aiming to more generally understand women’s perceptions of, attitudes about, and experiences with contraception.

Of the studies, 24 investigated LARCs, which included contraceptive implants (15), intrauterine devices (IUDs) (3), or both (6). An additional two studies focused on oral contraceptives, one on injectable contraception, and 21 on a combination of different forms of hormonal contraception. Two qualitative studies discussed contraceptive decision-making without specifying the forms of contraception.

The majority of studies targeted all women of reproductive age, with the lower age limit within the inclusion criteria (typically set at 18 years old) and the upper age limit between 44 and 50 years old. Twelve studies focused more specifically on adolescents or young adults, and one centered on midlife women.

Among the included studies that reported contraception discontinuation rates, high rates of early discontinuation were identified (as shown in Figure 2). The overall pooled discontinuation rate within 12 months or fewer of initiation was 26% (95% CI: 21–32%); however, discontinuation rates varied by contraceptive method. The hormonal contraceptive pill had the highest pooled discontinuation rate at 42% (95% CI: 20–67%). In contrast, the lowest discontinuation rate was observed for IUD use at 17% (95% CI: 11–24%). For implants and injectables, pooled discontinuation rates were 22% (95% CI: 16–28%) and 21% (95% CI: 7–40%) respectively. Studies reporting overall discontinuation for groups of women using multiple methods saw a pooled discontinuation rate of 38% (95% CI: 20–58%).

Table 2. Contributions to the Synthesis of the Impact of Side Effects on Discontinuation

First Author & Year | Side Effect Categories | |||||

Abnormal Bleeding | Weight Gain | Abdominal Pain & Cramping | Headache | Mood Changes | Sexual & GU | |

Adeyemi 2012 | • | • | • | |||

Akilimali 2020 | • | |||||

Al-Jefout 2015 | • | • | • | • | • | • |

Alspaugh 2021 | • | • | ||||

Austad 2020 | • | • | ||||

Bachofner 2018 | • | • | • | • | ||

Beesham 2021 | • | |||||

Bengtson 2013 | • | |||||

Berndt 2021 | • | |||||

Briggs 2016 | • | |||||

Burke 2021 | • | • | • | |||

Dasari 2016 | • | • | • | • | ||

Diedrich 2015 | • | • | ||||

Dolan 2021 | • | |||||

Ferreira 2014 | • | |||||

Flore 2016 | • | • | • | |||

Fruzzetti 2016 | • | • | • | • | • | |

Fruzzetti 2019 | • | • | • | • | ||

Gmedhin 2019 | ||||||

Grunloh 2013 | • | • | ||||

Higgins 2015 | • | • | ||||

Hirth 2021 | ||||||

Hladky 2011 | • | • | • | |||

Hoggart 2013a (Dickson) | • | • | • | • | ||

Hoggart 2013b | • | • | • | • | • | |

Jaisamrarn 2021 | • | • | • | |||

Johnson 2013 | • | • | ||||

Kelly 2019 | • | • | • | |||

Madden 2012 | • | • | • | • | • | |

Madden 2015 | • | • | • | • | • | |

Mandle 2017 | • | • | • | • | ||

Martin 2018 | • | • | • | • | • | |

Maslyanskaya 2016 | ||||||

Nageso 2018 | ||||||

Obijuru 2015 | • | • | ||||

Peterson 2019 | • | |||||

Roberts 2015 | • | • | • | |||

Roke 2016 | • | • | • | |||

Romano 2018 | • | |||||

Saloranta 2020 | • | • | • | • | ||

Sarfraz 2021 | • | • | ||||

Schmidt 2015 |

|

| • |

|

|

|

Schrumpf 2020 | • | • | • |

|

|

|

Simmons 2019 | • | • | • |

|

| • |

Sundell 2019 | • |

|

|

|

|

|

Tesfaye 2021 | • |

| • | • |

|

|

Teunissen 2014 |

| • |

| • | • |

|

Vickery 2013 |

| • |

|

|

|

|

Weisberg 2014 |

| • | • |

| • | • |

Wildemeersch 2017 |

| • |

|

| • | • |

Women opted to discontinue hormonal contraception for a variety of reasons, the most common of which were abnormal bleeding, weight gain, abdominal pain and cramping, headache, mood changes, and sexual and genitourinary side effects. Table 2 indicates which studies discussed each of these side effect categories.

Abnormal Bleeding

Women reporting abnormal bleeding discontinued their hormonal contraceptive method more often than women experiencing any other type of side effect. Eighty-nine percent of the included studies cited abnormal bleeding as the primary for discontinuation. For instance, studies reported that between 9.6% and 81.9% of women who discontinued injectable contraceptives did so due to abnormal bleeding.11,12 Several studies found that increased bleeding or irregular bleeding was the most frequent reason for contraceptive method discontinuation among LARC users (from 14.1% to 65.40%).13-15 Other studies found that abnormal bleeding caused by other forms of hormonal contraception led to discontinuation rates of between 5.3% and 15.0%.16,17

The qualitative studies corroborated the quantitative data, offering firsthand accounts of how abnormal bleeding could lead to hormonal contraceptive discontinuation.18-24 A typical account came from a 28-year-old user of a hormonal contraceptive implant: “There wasn’t really any gap where I didn’t have the spotting and that’s the main reason I did get it taken out.“20

Weight Gain

The second most commonly reported reason for hormonal contraceptive method discontinuation was weight gain, mentioned in 55.6% of the included studies. Quantitative studies indicated that between 1.4% and 40.9% of women who discontinued hormonal contraceptives did so due to weight gain.11,13,14

In qualitative studies, women frequently reported fear of weight gain as a barrier to initiating hormonal contraceptive methods. One woman using injectable contraceptives stated, “The shot made me gain a lot of weight. I gained 30 pounds 3 weeks after I had it”. 23

Abdominal Pain, Nausea, Vomiting, and Cramping

Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and cramping were indicated as reasons for discontinuing hormonal contraceptive methods in 33% of the included studies. Several studies found that between 2% and 40.47% of women who used LARCs stopped due to these negative side effects.13,25-28

Participants in qualitative studies reflected on their experiences with vomiting and cramping.21,23,24,29,30 A participant in her forties disclosed, “I haven’t regretted using family planning, but I was constantly getting sick after doing the 3-month injectable method. So, I stopped and got pregnant with my last born because I knew it was the 3-month injectable that was making me sick.”31

Headaches

Headaches were cited as a significant factor for discontinuing hormonal contraceptive methods in 26% of the included studies. For example, in the study by Jaisamrarn et al., 26 33% of women discontinued oral hormonal contraceptives due to headaches. Headaches were a frequently experienced side effect in the qualitative literature as well.21,22,29 They were generally reported with complaints of fatigue and/or mood changes and emotional liability, but also remained a compelling single cause of dissatisfaction. One 19-year-old implant user who discontinued contraceptives explained, “I had migraines; I’d be sleeping all the time. The headaches were crazy. I could wake up in the night and my head would be banging”.21

Mood Changes

Several studies identified mood changes as one of the reasons for discontinuing hormonal contraception methods. Thirty-three percent of the studies in this review cited mood alterations as a reason for cessation, with rates of discontinuation varying between 1.7 and 50%.17,25 One 31-year-old participant described having a “short fuse at my husband and kids all the time, which isn’t healthy,” which led her to discontinue using hormonal contraception. 20 A 17-year-old implant user noted feelings of depression she experienced while using an implant: “That’s never happened before. I was actually quite frightened”.21

Sexual & Genitourinary Side Effects

Changes in sex drive and sexual pleasure were also recognized as contributing factors to hormonal contraceptive discontinuation. Studies reported that between 5.5% and 46.4% of women discontinuing LARCs did so at least in part due to reduced libido.25,28,32 Studies looking at hormonal contraceptives more broadly found that a change in sexual pleasure or painful intercourse contributed to the discontinuation of contraception in 2.7% to 7% of women, and that a change in sex drive played an even larger role, with 6.3 to 9.9% of women attributing their decision to forgo hormonal contraception methods to reduced libido.14,33

Sexually transmitted infections and genitourinary-specific side effects were considered in four studies. A small number of participants in these studies did experience GU symptoms, including vaginitis, pelvic pain, abnormal discharge, swelling of the labia minora, and pelvic inflammatory disease, which contributed to both IUD and implant discontinuation, as well as dissatisfaction with progestogen-only injectables.11,28,34-36

The effect of hormonal birth control on sexuality and sexual satisfaction repeatedly appeared in the qualitative literature.18,20,21,37 Women reported decreases in sex drive and the impact of abnormal and breakthrough bleeding on their sex lives.20,21,37 As one woman explained, “[I] didn’t have regular sex, normal sex because of periods, and I wouldn’t like to have sex with someone on their period, it’s just not nice, so that was pretty much problems, everyday problems.”22

This review found that globally, more than one-quarter of women discontinue hormonal contraception within one year of initiation. Significantly, side effects heavily influence this choice, often outweighing the desire to continue the chosen hormonal contraceptive method—a finding that was consistent across diverse populations and varied geographic areas.

Abnormal bleeding and weight gain were the most frequently cited reasons for discontinuation, with each having ancilary factors that reinforced the decision to cease using hormonal contraception. For example, abnormal bleeding left women uncertain about their menstrual cycle, increased anemia among some patients, and interfered with women’s sex lives.

Early discontinuation has far-reaching implications on the health and welfare of women and the health system as a whole. The most immediate repercussion is the risk of unplanned pregnancies. Current threats on reproductive rights in the United States could make unplanned pregnancies increasingly hazardous due to restrictive abortion policies, which are linked to higher rates of increased maternal mortality.40 Further, this is ahealth equity issue, as Black women are less likely to receive an abortion referral when requested.41 The lack of abortion access, combined with racial disparities in maternal mortality, makes contraceptive continuation an important aspect of birth equity and a potentially life-saving practice.42 Moreover, at least ten countries in this review have stricter abortion restrictions than the United States, making contraception continuation an issue of global importance. 43

One notable strength of this review is the heterogeneity of the studies included, spanning various regions, types of hormonal contraceptive methods, and ranging over several years. However, given the statistical differences between contraception discontinuation between women from LMICs and women in the United States, future research should account for disparities that exist compared to high-income countries and diverse racial groups.

Another strength was the use of quantitative and qualitative methods, which provided added nuance in the synthesis process by capturing hard data on the number of people who discontinued hormonal contraception combined with people’s lived experiences concerning side effects and discontinuation. A clear limitation, however, was the absence of studies linking specific side effects to particular forms of hormonal contraception. This gap underscores the need for further research concerning the role side effects play and comprehensive pre-contraception counseling that addresses particular side effects for different methods.

Despite the growing popularity of hormonal contraceptives among women of reproductive age worldwide, the number of unintended pregnancies is still high. Our review indicates that many women appear to be discontinuing their chosen hormonal contraceptive method early due to contraceptive side effects. Future studies should explore stratageis for managing these side effects and explore additional ways to encourage consistent and continued use of contraception.

We want to thank Stella Seal, the Information Specialist who worked with us to finalize the search strategy and conduct the literature search in the database.

The authors have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Dr. Roberts is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Kinesiology & Public Health at California Polytechnic State University. She is a public health researcher who specializes in women’s sexual and reproductive health, including maternal & child health, cultural beliefs, and implicit bias and health disparities.

Katherine C. McNabb is a DNP/PhD candidate, a trainee with the Johns Hopkins Center for Infectious Disease and Nursing Innovation, and a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease Fellow. While her research typically focuses on HIV and related infectious diseases, in her nursing practice she is passionate about providing holistic care for people living with HIV, including comprehensive contraceptive care and sexual health services.

Alanna J. Bergman is a PhD candidate at Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing and trainee in the Johns Hopkins Center for Infectious Disease and Nursing Innovation. She is also a clinical nurse practitioner providing comprehensive care for people living with HIV. Through that work, she provides gynecological care and advocates for reproductive equity for people of color, sexual and gender minorities and those marginalized by infectious disease status. The National Institutes of Nursing Research funds her current research.

Dr.Taskin is a postdoctoral research associate in the Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology at the University of North Texas Health Science Center. Her career goal is to prevent cancer by identifying early-life mechanisms, including sociocultural and environmental factors, as well as developing and testing novel, precisely targeted interventions that promote health behavior. Dr. Taskin’s current research work will be able to identify emerging adults who are at risk of developing HPV-associated morbidities and mortalities and will help to develop evidence-based interventions.

Bella Mualem is a first year Masters of Public Health student at the University of Minnesota where she is concentrating in Maternal and Child Health under the Division of Epidemiology and Community Health. Her research and areas of interest are in sexual and reproductive health practices and increasing abortion access within the United States.

Dr. Oluwabunmi “Bunmi” Ogungbe is an Assistant Professor at Johns Hopkins School of Nursing and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. She is a cardiovascular epidemiologist dedicated to using her clinical, research, and public health expertise to improve cardiometabolic outcomes among populations experiencing social marginalization. She collaborates on several community-engaged multi-level interventions leveraging digital technologies to improve hypertension control and the management of chronic conditions. Dr. Ogungbe is an emerging leader in community-engaged research seeking to advance health equity, both locally in the US and globally.

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()