Ogbeide S, Gibson-Lopez G, Montanez M, Johnson-Esparza Y, Cordova T, Wiemers M. Utilizing the modified OMP model for health equity in a family medicine residency clinic. HPHR. 2023;72. 10.54111/0001/TTT1

Racial and ethnically diverse communities have higher mortality rates from chronic diseases. One approach to address health disparities and systemic racism in health care is through alterations in primary care workforce development via the One-Minute Preceptor (OMP) Teaching Method. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill created a modified OMP Model for Health Equity to address racial health disparities while teaching. This quality improvement (QI) project focuses on faculty confidence in discussing racial health disparities with learners using the modified OMP Model.

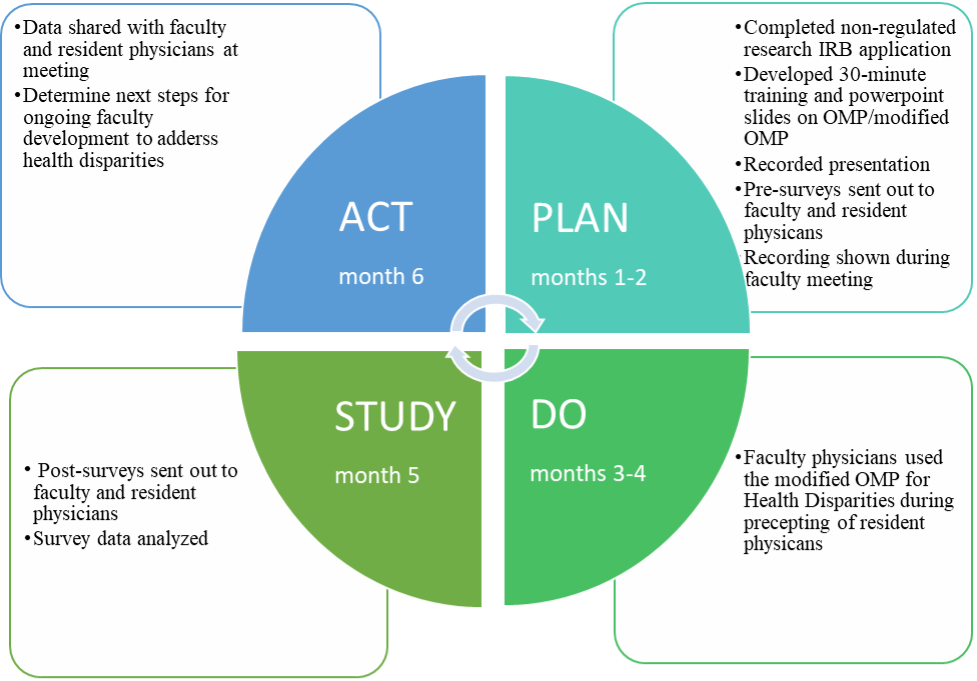

The QI project used a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) framework. Faculty participated in the Awareness, Reflection/Empowerment, and Action (AREA) survey, to assess level of engagement in addressing health disparities. Family Medicine (FM) residents completed a survey on current precepting practices of ethno-racial health disparities. Faculty were introduced to the modified OMP, followed by a two-month intervention period. Post-intervention surveys assessed the impact and identified faculty development opportunities. The intervention took place within a Family Medicine Residency Program, specifically during outpatient continuity clinics and the inpatient Family Medicine Hospital Service.

Faculty engagement increased in areas of awareness and action and decreased in reflection/empowerment. Residents reported higher satisfaction with Ethno-Racial health disparities clinical teaching after the intervention. Qualitative data suggests discussions are not occurring as often as residents desire and depend on different factors; race/ethnicity of the patient, clinical situation, social determinants of health impacting care, time, and preceptor.

The modified OMP for Health Equity intervention can be used to increase awareness and promote self-reflection and change.

The PDSA cycle framework for an intervention can improve faculty engagement addressing Ethnic-Racial health disparities.

Many racial and ethnically minoritized communities have higher mortality rates from chronic diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease than non-Hispanic Whites.1 According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 32% of Hispanic/Latinos, 22% of African Americans, 19% of Asian Americans and 30% of American Indians are uninsured compared to 14% of non-Hispanic Whites. The impact is documented in the primary care setting, with African Americans, Asian Americans, and Hispanic/Latinos less likely than non-Hispanic Whites to have a personal primary care provider. Racial and ethnically diverse populations are more likely than non-Hispanic Whites to report experiencing poor quality patient-provider interactions and perceived discrimination from the health care team.2 More than one approach will be needed to address health disparities and systemic racism in health care to achieve consistent health equity.3

In a recent review of existing literature on US-based graduate medical education programs that train residents to care for underserved populations and address health disparities showed that the majority of these programs were from primary care including pediatrics, family medicine, and internal medicine.4 A little over half (56%) of the programs in this review had defined learned competencies which included communication, cultural competency, research, and clinical skills. With regard to training format and content, half had longitudinal training, less than half (44%) had block experiences, and one reported a one-time internet-based module. About a quarter of these programs had residents complete a research project and about 38% included community-based clinical training. Most of the programs provided didactics, demonstrations, and small group discussions while one program offered graduate level courses in epidemiology and health policy. Two cited barriers for implementation of health equity education and training initiatives in residency programs include inadequate faculty training and insufficient interest in health equity education.5

Despite the urgency to overcome this barrier, there is limited literature on faculty development as it is related to racial equity in medical education. Falusi and colleagues developed a “teaching the teacher” racial equity curriculum that was well received and demonstrated increased knowledge and comfort with teaching health equity topics.6 Ross and colleagues developed another curriculum intended to upskill faculty in developing, implementing, and evaluating health disparities education.7 To address racial health disparities during brief clinical teaching, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill created a modified One-Minute Preceptor Model (OMP) for Health Equity.3 The OMP Teaching Method utilizes five micro skills (get a commitment, probe for supporting evidence, reinforce what was done well, give guidance about errors, and teach a general principle) guiding the faculty member’s interaction with brief teaching and immediate feedback to the learner.8-10 The modified OMP method for provides a structured approach for faculty to have targeted discussions relating to racial health equity with learners and focus on practical changes that learners and faculty can apply in practice to reduce racial health disparities.3

In an effort to further develop the primary care workforce, this quality improvement (QI) project focuses on assessing the level of faculty engagement in addressing health disparities and residents’ perception of the intervention, discussing racial health disparities with learners during precepting time using the modified OMP Model for Health Disparities. Recently, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has issued the most significant changes to residency training requirements seen to date, which will be effective July 2023. The new program requirements are aimed at training resident physicians in ways that enhance health equity and population health in the communities they serve. This QI project could serve as an example for programs to implement health equity longitudinally throughout residency training.

Faculty physicians and residents completed the AREA survey (faculty), precepting practice survey (residents), and demographic information electronically one month prior to the modified OMP for Health Disparities intervention (“plan” stage of PDSA; see Figure 1). Faculty physicians were introduced to the intervention through a brief (30 minute) didactic training during a faculty meeting. During the didactic training, a 30-minute pre-recorded video lecture was played reviewing health disparities and the importance of achieving health equity in primary care, an overview of OMP, and the modified OMP Model for Health Equity. Within the video, an example of a preceptor working with a resident without the modified OMP Model and with the modified Model was played. After the video was played, a live Q and A session took place to discuss questions related to implementing the modified OMP Model on the inpatient and outpatient services. Faculty physicians then began use of the intervention for a two-month period. After the intervention (“do” stage of PDSA), physicians completed the AREA survey to assess impact of the modified OMP for Health Disparities (“study” stage) and the brief didactic training to determine next steps for ongoing faculty development to address health disparities with learners (“act” stage). This QI project was deemed non-regulated research by the UTHSCSA IRB (#20210532NRR).

Population and Setting: FM Physician Core Faculty and Residents within the FM Residency (FMR). Implementation of this QI project used a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) framework.11 Instruments: Administration of the 9-item Awareness, Reflection/Empowerment, and Action (AREA) survey12 to all physician faculty to assess level of engagement in addressing health disparities (see Table 1). A survey developed by the QI team on current precepting practices in the context of ethno-racial health disparities is administered to all FM residents.

|

Table 1. AREA Survey Items |

|

Awareness a |

|

1. Across the United States, minority patients generally receive lower quality care than white patients. |

|

2. Some minorities with heart disease are less likely than whites with heart disease to get specialized medical procedures and surgery. |

|

3. Whites with HIV or AIDS are more likely than some minorities with HIV or AIDS to get the newest medicines and treatments. |

|

Reflection/Empowerment a |

|

4. It is important for physicians to devote extra time to the health needs of their minority patients. |

|

5. I often think about what I can do to interact more effectively with my minority patients. |

|

6. I am in a position to make a difference in the quality of health care that minority patients receive. |

|

Action b |

|

7. In the last month, I have spoken with colleagues about ways to address specific health care needs of minority patients. |

|

8. In the last month, I have worked with a community group to address a local health problem. |

|

9. In the last month, I have participated in a quality improvement project at my place of work to increase quality of care for minority patients. |

a Likert scale: 1=strongly disagree; 5=strongly agree

b Binary: 1=no; 2=yes

The following demographic information was captured for physician faculty: Age, Race/Ethnicity, Gender, Years in practice, Years as an educator in FM (see Table 2). The following demographic information was also captured for FM residents: Age, Race/Ethnicity, Gender, and PGY (see Table 2).

|

Table 2. Sample Characteristics of Family Medicine Faculty and Residents |

||

|

Faculty demographics |

Pre-test survey (N=12) |

Post-test survey (N=8) |

|

Mean age (range) |

||

|

Years |

50 (38-64) |

47 (36-61) |

|

Gender (%) |

||

|

Male |

60 (n=6) |

12.5 (n=1) |

|

Female |

40 (n=4) |

87.5 (n=7) |

|

Non-binary |

0 |

0 |

|

Other |

0 |

0 |

|

Race (%) |

||

|

White |

40 (n=4) |

37.5 (n=3) |

|

Hispanic/Latino |

40 (n=4) |

37.5 (n=3) |

|

Asian American/Pacific Islander |

10 (n=1) |

25 (n=2) |

|

Multiracial |

10 (n=1) |

0 |

|

African American/Black |

0 |

0 |

|

Native American/American Indian |

0 |

0 |

|

Years in Family Medicine practice (%) |

||

|

0-5 |

0 |

0 |

|

6-10 |

30 (n=3) |

37.5 (n=3) |

|

11-15 |

10 (n=1) |

12.5 (n=1) |

|

16-20 |

30 (n=3) |

12.5 (n=1) |

|

21+ |

30 (n=3) |

37.5 (n=3) |

|

Years in Family Medicine residency (%) |

||

|

0-5 |

10 (n=1) |

12.5 (n=1) |

|

6-10 |

40 (n=4) |

37.5 (n=3) |

|

11-15 |

0 |

0 |

|

16-20 |

30 (n=3) |

25 (n=2) |

|

21+ |

20 (n=2) |

25 (n=2) |

|

Faculty appointment level (%) |

||

|

Assistant professor |

30 (n=3) |

50 (n=4) |

|

Associate professor |

20 (n=2) |

25 (n=2) |

|

Full professor |

50 (n=5) |

25 (n=2) |

|

Resident demographics |

Pre-test survey (N=28) |

Post-test survey (N=32) |

|

Mean age (range) |

||

|

Years |

30 (25-40) |

31 (26-41) |

|

Gender (%) |

||

|

Male |

23.08 (n=6) |

15.63 (n=5) |

|

Female |

76.92 (n=20) |

84.38 (n=27) |

|

Non-binary |

0 |

0 |

|

Other |

0 |

0 |

|

Race (%) |

||

|

White |

23.08 (n=6) |

21.88 (n=7) |

|

Hispanic/Latino |

46.15 (n=12) |

46.88 (n=15) |

|

African American/Black |

11.54 (n=3) |

9.38 (n=3) |

|

Asian American/Pacific Islander |

19.23 (n=5) |

15.63 (n=5) |

|

Multiracial |

0 |

6.25 (n=2) |

|

Native American/American Indian |

0 |

0 |

|

Current training year (%) |

||

|

PGY1 |

38.46 (n=10) |

25 (n=8) |

|

PGY2 |

19.23 (n=5) |

37.5 (n=12) |

|

PGY3 |

42.31 (n=11) |

37.5 (n=12) |

Figure 1. PDSA Cycle and Timeline

To analyze the quantitative data, descriptive statistics were performed to provide a summary of the data. The AREA survey was completed by 12 out of 14 (86%) FM core residency faculty prior to the intervention and 8 (66.7%) faculty after the intervention (see table 3). Prior to the intervention, the majority of faculty demonstrated engagement in the areas of awareness and reflection/empowerment while lower engagement levels were seen in action. After the intervention, faculty engagement levels slightly increased in the areas of awareness and action and slightly decreased in reflection/empowerment.

|

Table 3. AREA Survey Outcomes for Faculty |

||||

|

|

Pre-modified OMP |

Post-modified OMP |

||

|

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

|

Awareness a |

4.00 |

1.32 |

4.25 |

0.70 |

|

Reflection/Empowerment a |

4.83 |

0.36 |

4.50 |

0.51 |

|

Action b |

1.53 |

.49 |

1.58 |

.49 |

a Likert scale: 1=strongly disagree; 5=strongly agree

b Binary: 1=no; 2=yes

A total of 28 out of 42 (66.7%) FM residents completed the pre-survey and 32 (76.2%) completed the post-survey on precepting practices (see table 4). Using a 1-7 Likert scale, where higher numbers indicate discussions occurring very often and residents being very satisfied, residents reported that discussions of Ethno-Racial health disparities occurred often during precepting at the Family Health Center (FHC) or at the FM Hospital Service (FMHS) both before the intervention and after. Residents reported overall satisfaction with the clinical teaching about Ethno-Racial health disparities prior to the intervention and slightly higher satisfaction after the intervention. To analyze the qualitative data, a thematic analysis was performed. The qualitative data suggests that 1: Although discussions are being held, they are not occurring as often as residents would like and are dependent on various factors such as race/ethnicity of the patient, the clinical situation, social determinants of health impacting care, time, and preceptor, and 2: Although residents were satisfied, many would like more clinical and didactic teaching on Ethno-Racial health disparities in both inpatient and outpatient settings.

|

Table 4. Resident Survey Outcomes |

||||

|

|

Pre- Modified OMP |

Post- Modified OMP |

||

|

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

|

Please rate how often ethno-racial health disparities are discussed during precepting at the Family Health Center or at the Family Medicine Inpatient Service? a |

4.07 |

1.58 |

4.06 |

1.58 |

|

How satisfied are you with clinical teaching about ethno-racial health disparities through precepting at the Family Health Center or at the Family Medicine Inpatient Service? b |

4.04 |

1.59 |

4.66 |

1.59 |

a Likert Scale: 1= not often; 7= very often

b Likert Scale: 1= not satisfied; 7= very satisfied

We learned that by using the PDSA cycle framework for QI, FM faculty engagement in addressing Ethnic-Racial health disparities may improve. The modified OMP Model for Health Equity intervention can be used as a concrete tool to impact awareness and to promote self-reflection and change on issues of Ethno-Racial health disparities. Repeated cycles will be needed to ensure more frequent and continued use in teaching experiences.

Our study has limitations, including the variability in response rate pre- and post-intervention, limiting robust pre and post comparisons. Additionally, only descriptive statistics were performed, limiting the generalizability of the impact of this QI project. Further, depending on what services residents were rotating through, it is possible that they were not sufficiently exposed to the modified OMP for Health Equity, thus impacting their willingness to respond with their ratings. It is also worth noting that our residency, although not reflective of the demographics of the nation, is diverse relative to other residencies across the nation, potentially limiting the generalizability to other residencies. Given the nature of this study, we did not consider the ongoing use of the modified OMP for Health Equity or its long-term benefit, though this is an area of future study. This QI project can serve as an example for programs to implement health equity longitudinally throughout residency training and can inform future quality improvement projects that strive to train the primary care workforce to enhance health equity and population health in the communities they serve.

The authors have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

1 Kaiser Family Foundation. Key Facts on Health and Health Care by Race and Ethnicity. 2022. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-facts-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/. Accessed November 20, 2022

2 Sorkin DH, Ngo-Metzger Q, De Alba I. Racial/ethnic discrimination in health care: impact on perceived quality of care. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(5):390-396. doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1257-5

3Amidon J, Overstreet Galeano MA, Brendle DC, Lam Y, Waters Davis J, Panigrahi K. A model to engage learners in discussions on health equity and implicit bias. The Scholarly Teacher. Published June 8, 2022. Accessed April 3, 2023. https://www.scholarlyteacher.com/post/a-model-to-engage-learners-in-discussions-on-health-equity-and-implicit-bias.

4 Hasnain M, Massengale L, Dykens A, Figueroa E. Health disparities training in residency programs in the United States. Fam Med. 2014;46(3):186-191.

5 Dupras DM, Wieland ML, Halvorsen AJ, Maldonado M, Willett LL, Harris L. Assessment of Training in Health Disparities in US Internal Medicine Residency Programs. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2012757. Published 2020 Aug 3. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12757

6 Falusi O, Chun-Seeley L, de la Torre D, et al. Teaching the Teachers: Development and Evaluation of a Racial Health Equity Curriculum for Faculty. MedEdPORTAL. 2023;19:11305. Published 2023 Mar 28. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11305

7 Ross PT, Wiley Cené C, Bussey-Jones J, et al. A strategy for improving health disparities education in medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S160-S163. doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1283-3

8 Green LA, Miller WL, Frey JJ, et al. The time is now: A plan to redesign Family Medicine residency education. Family Medicine. 2022;54(1):7-15. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2022.197486.

9 Shagholi R, Naimie Z, Abuzaid, RA. One-Minute Preceptor (OMP) applied teaching method. New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences. 2021;8(3):51–59. https://doi.org/10.18844/prosoc.v8i3.6397.

10 STFM Resource Library. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/

11 Del Castillo FA. Plan-do-study-act cycle: resilient health systems through continuous improvement. Journal of Public Health. 2021;44(2):e297–e298. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab211.

12 Alexander GC, Lin S, Sayla MA, et.al. Development of a measure of physician engagement in addressing racial and ethnic health care disparities. Health Services Research. 2008;43(2):773–784. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00780.x.

Dr. Ogbeide is an Associate Professor of Family & Community Medicine on the tenure track at UT Health San Antonio. She also serves as an Assistant Dean for Faculty for the Long School of Medicine at UT Health San Antonio. Her professional areas of interest include: Primary Care Behavioral Health, Behavioral Medicine, Workforce Development, and Faculty Development

Dr. Gibson-Lopez is an Assistant Professor/Clinical in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at UT Health San Antonio. Her professional areas of interest include: Primary Care Behavioral Health and Health Disparities.

Dr. Montanez is an Associate Professor/Clinical in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at UT Health San Antonio. Her professional areas of interest include: Graduate Medical Education, Psychosocial and Family Medicine, and Health Disparities.

Dr. Johnson-Esparza is an Assistant Professor/Clinical in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at UT Health San Antonio. Her professional areas of interest include: Primary Care Behavioral Health, Health Disparities, and Graduate Medical Education.

Dr. Cordova is an Associate Professor/Clinical in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at UT Health San Antonio. Her professional areas of interest include: Women’s Health, Family Medicine, and Graduate Medical Education.

Dr. Wiemers is an Associate Professor/Clinical in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at UT Health San Antonio. Her professional areas of interest include: Women’s Health, Family Medicine, and Graduate Medical Education.

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()