Akinwumi B, Akinyemi O, Fasokun M, Salihu E, Agunwa N, Urby H. Self-regulation, dietary habits, and obesity trends among female college students. HPHR. 2023;64. 10.54111/0001/LLL3

Dietary habits and self-regulation are crucial in weight management, particularly among female college students. These students, navigating transitional life stages and academic stressors, often grapple with making healthy food choices. Understanding their self-confidence in resisting overeating and unhealthy foods can shed light on obesity trends within this demographic.

We determine the association between self-reported individual-level confidence in resisting the urge to overeat or choose less healthy food options and obesity among female college students.

From August 10 to October 20, 2019, a cross-sectional survey was conducted among female students at Western Illinois University. Using a Likert scale, we gauged self-reported confidence in resisting overeating or unhealthy food choices. Responses were numerically scored (5-55), with higher scores indicating greater confidence. These scores were integrated into a multivariate analysis, investigating associations with obesity and depression risks, adjusted for age, race, and academic year.

Of 375 female students meeting the criteria, the racial breakdown was 60.8% white, 21.9% black, 8.3% Hispanic, and 9.1% other. Age 18-21 covered 66.2%. BMIs were 44.0% normal, 21.9% overweight, and 30.1% obese. Depression was clinically diagnosed in 23.2%. The median dietary score was 34 (IQR 31-39).Every dietary score unit increase reduced the risk of being underweight by 3.9% (RR=0.96, 95% CI 0.89-1.04, P=0.31), overweight by 4.5% (RR=0.96, 95% CI 0.92-0.99, P=0.022), and obese by 5.7% (RR=0.94, 95% CI 0.91-0.98, P=0.004) relative to normal BMI. Significant predictors of self-reported depression include being underweight or obese, being White, and having a family history of obesity.

In this cohort of college students in Macomb, female students with stringent dietary practices are less prone to overweight or obesity.

The rapid transition from adolescence to adulthood, characterized by the college years, is a pivotal time in the lives of many young adults. It is a period marked by newfound freedom, academic pressures, and the need for self-reliance. Consequently, college students, particularly females, are at an intersection of numerous challenges related to nutrition and body image.1-2 Historically, college campuses have been epicenters of both enlightenment and struggles, and the domain of dietary habits is no exception.3-4

In contemporary times, the prevalence of obesity has reached epidemic proportions globally.5-6 The reverberations of this crisis can be felt profoundly within the collegiate environment. Not only does obesity present physical health ramifications, but it also carries a myriad of psychological and social implications.7-8 Obesity during these formative years can influence self-esteem, social interactions, and academic performance.9

While the global statistics on obesity are alarming, it is the individual dietary choices and habits that aggregate to these staggering numbers.5 For a female college student, these choices are influenced by myriad factors: peer pressure, academic stress, accessibility to healthy food options, and personal beliefs and knowledge about nutrition.10-12 Furthermore, their ability to self-regulate amidst the abundance of often unhealthy and convenient food choices on and around campuses is of paramount importance. This self-regulation is intrinsically linked to one’s confidence in making the right dietary choices, impacting their overall health trajectory.

Given the above, it becomes imperative to delve deeper into understanding the nuances of dietary habits, the power of self-regulation, and the prevalent trends in obesity among female college students. This is especially crucial in areas like Macomb, which may reflect a broader spectrum of college towns. By gauging their self-confidence in resisting the allure of overeating and unhealthy foods, we may gain insights that can aid in tailored interventions, thereby potentially reversing or curbing the trend of obesity within this crucial demographic.

The rapid transition from adolescence to adulthood, characterized by the college years, is a pivotal time in the lives of many young adults. It is a period marked by newfound freedom, academic pressures, and the need for self-reliance. Consequently, college students, particularly females, are at an intersection of numerous challenges related to nutrition and body image.1-2 Historically, college campuses have been epicenters of both enlightenment and struggles, and the domain of dietary habits is no exception.3-4

In contemporary times, the prevalence of obesity has reached epidemic proportions globally.5-6 The reverberations of this crisis can be felt profoundly within the collegiate environment. Not only does obesity present physical health ramifications, but it also carries a myriad of psychological and social implications.7-8 Obesity during these formative years can influence self-esteem, social interactions, and academic performance.9

While the global statistics on obesity are alarming, it is the individual dietary choices and habits that aggregate to these staggering numbers.5 For a female college student, these choices are influenced by myriad factors: peer pressure, academic stress, accessibility to healthy food options, and personal beliefs and knowledge about nutrition.10-12 Furthermore, their ability to self-regulate amidst the abundance of often unhealthy and convenient food choices on and around campuses is of paramount importance. This self-regulation is intrinsically linked to one’s confidence in making the right dietary choices, impacting their overall health trajectory.

Given the above, it becomes imperative to delve deeper into understanding the nuances of dietary habits, the power of self-regulation, and the prevalent trends in obesity among female college students. This is especially crucial in areas like Macomb, which may reflect a broader spectrum of college towns. By gauging their self-confidence in resisting the allure of overeating and unhealthy foods, we may gain insights that can aid in tailored interventions, thereby potentially reversing or curbing the trend of obesity within this crucial demographic.

We conducted a cross-sectional survey using convenience sampling to recruit female students at Western Illinois University between August 10 and October 20, 2019.

The primary objective of the study was to determine the association between self-reported individual-level confidence in resisting the urge to overeat or select less healthy food options and the prevalence of obesity among female college students. We adopted the World Health Organization’s criteria for obesity, defining it as a Body Mass Index (BMI) of 30.0 or higher. Healthy weight was categorized as a BMI ranging from 18.5 to 24.9, and overweight was categorized as a BMI between 25.0 and 29.9. Respondents were requested to provide their height and weight, from which we calculated their BMI scores. Using a Likert scale, we gauged self-reported confidence in resisting overeating or unhealthy food choices. Responses were numerically scored (5-55), with higher scores indicating greater confidence. These scores were utilized as a continuous variable and inputted into our analysis. A secondary aim was to assess the relationship between this self-reported confidence and depression.

We included female students aged between eighteen and twenty-four years who are attending Western Illinois University in Macomb. On the other hand, we excluded students from the Quad City campus, any students older than twenty-four years from both Macomb and Quad City campuses, all male students, and all faculty members.

Following approval from the Institutional Review Board, an email was distributed to enrolled students through the Administrative Information Management System (AIMS) and the university’s TeleSTARS system. This communication included a web link to access an anonymous survey created on Google Forms.

The research survey comprised an informed consent section and three distinct questionnaire sections labeled (a), (b), and (c). Section (a) gathered general participant information, section (b) assessed self-reported confidence in resisting overeating or unhealthy food choices using a 5-point Likert scale (the choices ranged from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree”), and section (c) focused on queries related to associated medical conditions. Sections (a) and (c) were structured as ‘yes’ or ‘no,’ while section (b) utilized the Likert scale.

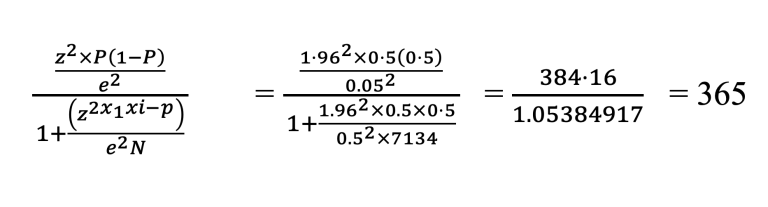

Western Illinois University-Macomb campus’s total undergraduate student population is 7,134, with 51% female students and an average class size of 20.5 students. On average, there are 21 registered undergraduate students per course, with 11 females constituting 51% of the total students per class. For this study, a 95% confidence level, a significance level of 0.05, and a margin error of ±5% were applied using a simple random sampling technique.

The sample size for this research comprised 365 female undergraduates (representing 10.1% of the total female undergraduate population). This was calculated using the sample size formula below:

Responses from the Likert scale was converted to a numerical score ranging between 5 and 55. A score of 5 represented the lowest level of confidence (akin to “Strongly Disagree”), whereas a score of 55 indicated the highest level of confidence (akin to “Strongly Agree”). This scoring system was devised such that a lower score indicated a lower level of self-reported confidence in resisting the urge to overeat or choose less healthy food options. Conversely, a higher score suggested a greater degree of confidence.

Descriptive statistics were employed to elucidate the baseline attributes of the study participants and pertinent risk factors, articulating categorical variables as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were depicted through medians and interquartile ranges. An exploration of the association between baseline characteristics and obesity risk was conducted utilizing chi-square statistics.

To evaluate disparities in categorical and continuous variables, chi-square and independent sample t-tests were respectively utilized, with baseline characteristics stratified across diverse BMI classes, namely underweight, normal, and obesity, through chi-square tests.

Further, a multinomial regression model was employed to investigate the association between Total Score (a metric for self-control) and varied obesity classes, referencing normal BMI. Reporting was selectively restrained to obesity results, omitting others due to limited sample sizes. The regression model was additionally informed by covariates including age, race/ethnicity, academic year, and a familial history of obesity in first-degree relatives.

A sub-analysis aimed at discerning the association between the Total Score and self-reported depression was undertaken, adjusting for the previously noted covariates. Outcomes were articulated in odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), adopting a statistical significance threshold determined by a two-tailed p-value < 0.05. All statistical evaluations were executed using STATA 16 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

In this study, 375 students met the study inclusion criteria. Participants aged 18-21 years represented a majority (66.2%), with a significantly higher prevalence of normal BMI compared to those >21 years (73.3% vs. 26.7%, p=0.042). A noteworthy 34.3% of participants had a family history of obesity, which was substantially more common in obese individuals (58.1%) compared to their normal BMI counterparts (21.2%, p<0.001). Depression was identified in 23.2% of participants, being more prevalent among obese individuals (32.4%) than those with a normal BMI (14.6%, p=0.001). No significant differences among BMI categories were identified regarding race and school year (Table 1).

Table 1: Baseline Characteristics

Variables | Total (N=375) | Obese (n=113) | Normal BMI (n=165) | P-value |

Age | 0.042* | |||

18-21yrs | 243 (66.2%) | 61 (58.1%) | 121 (73.3%) | |

> 21 yrs. | 124 (33.8%) | 44 (41.9%) | 44 (26.7%) | |

Race | 0.061 | |||

White | 228 (60.8%) | 54 (47.8%) | 116 (70.3%) | |

Black | 82 (21.9%) | 30 (26.6%) | 30 (18.2%) | |

Hispanic | 31(8.3%) | 14 (12.4%) | 8 (4.9%) | |

Family history of obesity | 126 (34.3%) | 61 (58.1%) | 35 (21.2%) | < 0.001* |

School Year | 0.819 | |||

Freshmen | 74 (20.2%) | 21 (20.0%) | 35 (21.2%) | |

Sophomore | 122 (33.2%) | 28 (26.7%) | 56 (33.9%) | |

Junior | 112 (30.5%) | 37 (35.2%) | 47 (28.5%) | |

Senior | 59 (16.1%) | 19 (18.1%) | 27 (16.4%) | |

Total Score | 34 (IQR 31-39) | 34 (29-38) | 35 (32-40) | < 0.001* |

Depression | 85 (23.2%) | 34 (32.4%) | 24 (14.6%) | 0.001* |

* Represents statistical significance with p < 0.05. ** The total sample size was 375. However, we compared only obese patients (113) and patients with normal BMI (165). The remaining students were suppressed because of the small sample size < i.e., Underweight = 10, overweight =48

Table 2: Multinomial Regression prediction of membership of BMI categories with normal BMI as reference

Classes of BMI ( 95% CI) | |||

Variables | Underweight | Overweight | Obese |

Age > 21 yrs. | 1.26 (0.89-1.04) | 2.35 (1.12-4.90) | 2.20 (1.06-4.57) |

Race | |||

White | Reference | Reference | Reference |

Black | 1.70 (0.42-6.95) | 1.92 (0.95-3.86) | 2.93 (1.49-5.77) * |

Hispanic | 1.57 (0.17-14.54) | 2.65 (0.92-7.63) | 4.12 (1.52-11.15) * |

School Year | |||

Freshmen | Reference | Reference | Reference |

Sophomore | 1.56 (0.28-8.80) | 0.97 (0.44-2.12) | 0.61 (0.27-1.37) |

Junior | 1.08 (0.14-8.28) | 0.61 (0.23-1.58) | 0.76 (0.30-1.92) |

Senior | 1.65 (0.25-11.00) | 0.72 (0.28-1.89) | 0.93 (0.38-2.28) |

Family History of obesity | 0.61 (0.15-2.41) | 1.53 (0.81-2.88) | 4.27 (2.37-7.69) * |

Depression | 5.79 (1.81-18.46) * | 1.86 (0.92-3.77) | 2.26 (1.16-4.41) * |

Total Score | 0.96 (0.89-1.04) | 0.96 (0.92-0.99) * | 0.94 (0.91-0.98) * |

* Represents statistical significance with p < 0.05.

In analyzing the association between predictors and different BMI categories (Table II), using normal BMI as the reference, the Total Score emerged as a significant predictor for both overweight and obese groups. Each unit increase in the Total Score was associated with a 4.5% reduction in the risk of being overweight (Relative Risk Ratio (RRR) = 0.955, 95% CI: 0.918-0.993, p = 0.022) and a 5.7% reduction in the risk of being obese (RRR) = 0.943, 95% CI: 0.906-0.982, p = 0.004). The Total Score, however, was not significantly associated with the underweight category (RRR = 0.961, p = 0.310).

When examining other factors, self-reported depression was strongly associated with underweight (RRR = 5.79, 95% CI: 1.818-18.454, p = 0.003). Racial differences were prominent for the obese category. Specifically, black and Hispanic individuals had a significantly higher risk of being obese, nearly three-fold (RRR = 2.93, p = 0.002) and over four-fold (RRR = 4.12, p = 0.005), respectively, compared to the reference racial group. A family history of obesity was the strongest predictor for the obese category, increasing the risk by over fourfold (RRR = 4.27, 95% CI: 2.368-7.691, p = 0.000).

Table 3: Risk factors for self-reported obesity

Depression | Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | P-value | |

Lower CI | Upper CI | |||

Age > 21yrs. | 0.68 | 0.34 | 1.37 | 0.281 |

Total Score | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.818 |

BMI | ||||

Normal | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

Underweight | 5.99 | 1.89 | 19.01 | 0.002* |

Overweight | 1.96 | 0.96 | 3.98 | 0.063 |

Obese | 2.27 | 1.16 | 4.45 | 0.017* |

Race | ||||

White | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

Black | 0.41 | 0.20 | 0.83 | 0.014* |

Hispanic | 0.59 | 0.23 | 1.52 | 0.272 |

Family History of obesity | 4.27 | 2.37 | 7.69 | < 0.001* |

School Year | ||||

Freshmen | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

Sophomore | 1.32 | 0.60 | 2.90 | 0.491 |

Junior | 2.01 | 0.81 | 4.98 | 0.133 |

Senior | 1.78 | 0.75 | 4.23 | 0.191 |

* Represents statistical significance with p < 0.05

In examining the relationship between various factors and the risk of self-reported depression (Table III), a logistic regression analysis was performed. The key predictor variable, TotalScore, was not significantly associated with self-reported depression (Odds Ratio (OR) = 1.004, 95% CI: 0.968-1.042, p = 0.818). This indicates that for every unit increase in TotalScore, the odds of reporting depression increased by only 0.4%, a change that is not statistically significant.

When analyzing other variables, the most profound associations with depression were seen with BMI categories. Relative to the normal BMI group, being underweight significantly increased the risk of depression by nearly six-fold (OR = 5.99, 95% CI: 1.888-19.013, p = 0.002). The obese category also had a significant association with a more than two-fold increased risk (OR = 2.27, 95% CI: 1.157-4.447, p = 0.017). Overweight individuals showed a trend towards increased risk, but the association was marginally significant (OR = 1.96, p = 0.063).

Race played a role in depression risk as well, with black individuals having a significantly reduced risk compared to the reference group (OR = 0.41, 95% CI: 0.197-0.833, p = 0.014). The presence of obesity in the family was another strong predictor, tripling the risk of depression (OR = 3.06, 95% CI: 1.758-5.335, p =0.000).

In our study, the Total Score, which gauges individual self-reported confidence in resisting the urge to overeat or opt for less healthful food choices, revealed a nuanced relationship with BMI categories. With the Normal BMI group as the reference, a higher score appeared to reduce the likelihood of being in the obese category (RRR=0.943, p=0.004) and the overweight category (RRR=0.955, p=0.022). In contrast, the same increased score was not significantly associated with underweight (RRR=0.961, p=0.310).

This observation aligns with the findings of López-Contreras et al. (2000), where individuals with higher confidence in resisting unhealthy food choices had a lower risk of obesity.13-15 They proposed that such individual-level confidence might act as a buffer against external food-related temptations, subsequently affecting BMI outcomes. However, our results diverge from the study by Medrano-Vázquez’s et al. (2014), which did not find a significant association between self-regulation and BMI categories.16 It’s worth noting that our study, with a larger sample size and more diverse participant demographics, offers a more comprehensive perspective. This might explain the disparities in the findings.

The implications of our findings are profound, emphasizing the significance of psychological determinants in predicting BMI outcomes. Interventions focusing on boosting individual confidence and self-regulation against unhealthy food choices might prove beneficial in obesity prevention.

Our study also highlighted several other notable associations. Age appeared to be a significant factor in being overweight or obese, with older students more likely to fall into these categories. Furthermore, the presence of obesity in the family substantially increases the risk of being obese. These findings underscore the multifactorial nature of BMI determinants, echoing the complex interactions between genetic, environmental, and individual factors.17-19

The relationship between the confidence score and self-reported depression was not statistically significant in our analysis (OR=1.004, p=0.818). This indicates that individual self-reported confidence in resisting unhealthy food choices may not directly correlate with self-reported depressive states.

This observation contrasts with the study by Kris-Etherton et al. (2020), where individuals with better dietary self-regulation reported fewer depressive symptoms.20-21 A possible explanation for the discrepancy could be our study’s emphasis on “confidence” rather than actual “ability” to resist, suggesting that belief in one’s capability may not necessarily translate to tangible mental health benefits.

Given the prevalence and burden of depression, understanding its determinants is critical. While our study suggests that the confidence to resist unhealthy food choices might not be a direct protective factor against depression, it’s crucial to consider the broader implications of diet and mental health.

Apart from the primary variable of interest, the present study pinpointed some vital associations. Being underweight was considerably associated with higher odds of reporting depression (OR=5.99, p=0.002), consistent with numerous studies suggesting a bi-directional relationship between low BMI and mental health disorders.22-23 Race also emerged as a significant predictor, with Black participants less likely to report depression compared to other racial groups. The presence of obesity in the family was also linked with a higher likelihood of self-reported depression. These observations underscore the myriad of factors interplaying in the manifestation of depression, necessitating a holistic approach to mental health interventions.

Cultural and socioeconomic factors significantly shape dietary habits and self-regulation among college students. Cultural background influences food preferences, meal patterns, and eating behaviors.24 Socioeconomic status (SES) is another crucial determinant impacting access to healthy foods and nutritional knowledge.25 Recent studies emphasize the persistent influence of these factors on college students’ dietary choices and overall health.26 Interventions addressing dietary habits must be culturally sensitive, considering diverse backgrounds and acknowledging socioeconomic disparities.27 Understanding these influences is essential for developing effective strategies that promote healthy eating and self-regulation among college students, fostering overall well-being and academic success.

This study underscores the importance of individual self-regulation and confidence in determining health outcomes. Addressing social justice in college students’ dietary habits demands attention to disparities in food access, health education, and self-regulation, often influenced by socioeconomic and cultural factors. Marginalized communities may struggle with affordability, limited nutritional knowledge, and self-regulation barriers. Policies should target these determinants, promoting nutritional education, affordable campus food options, and culturally sensitive health strategies. Empowering students through educational programs, accessible resources, and peer support fosters confidence and self-regulation. A holistic approach is crucial for achieving equity, ensuring all students, regardless of background, have equal opportunities for healthy living in a supportive college environment.

Policymakers should prioritize the integration of psychological determinants into public health interventions. Targeted programs that bolster individual-level confidence in resisting unhealthy food temptations might be pivotal in combating obesity. While confidence alone may not shield against depression, a comprehensive approach, recognizing the multifactorial nature of health outcomes, is paramount. Investing in such tailored interventions can enhance public health efforts, promote healthier societies, and reduce healthcare burdens.

While this study offers valuable insights, there are limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature precludes establishing causality between variables. Future research should employ longitudinal designs, allowing for the examination of changes over time and providing stronger evidence for causal relationships. Second, the reliance on self-reported measures might introduce response biases, affecting the validity of our results. Third, the study’s moderate sample size and its focus on a single university could restrict the broad generalizability of its findings to diverse populations. Universities vary widely in their cultures and campus environments, influencing dietary behaviors and self-regulation differently. Additionally, the influence of local cultural and regional factors on dietary habits, lifestyle, and overall health underscores the potential challenges in applying these results to female students in different geographical regions or cultural contexts.

Our findings underscore the multifaceted nature of health determinants, illuminating the intricate dance between psychological constructs, such as confidence in resisting unhealthy food choices, and tangible health outcomes. While our study broadens the understanding, it also emphasizes the need for interventions tailored to individual psychosocial characteristics. As we advance in the domain of public health, studies like ours pave the path for more targeted and effective health strategies.

The author(s) have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Bolarinwa Akinwumi is a dedicated and performance-oriented healthcare professional passionate about Public Health. He brings extensive clinical expertise gained over many years of patient care and management. Dr. Akinwumi’s journey in the field of medicine and healthcare began in Nigeria, where he completed his medical degree at Ladoke Akintola University of Technology. His academic journey continued as he pursued a Master of Science in Public Health, which he successfully obtained from Western Illinois University USA in 2019. Before transitioning to the United States, Dr. Akinwumi accumulated several years of experience as a physician at the Mother and Child Hospital, University of Medical Sciences, Nigeria. His ability to seamlessly integrate the worlds of public health and clinical practice sets him apart in the field. His research experience spans a wide array of medical specialties, including hematology, oncology, endocrinology, neurology/psychiatry, surgery, and the cardiovascular system. Dr. Akinwumi’s research pursuits are dedicated to enhancing health outcomes among diverse socioeconomic groups, reflecting his commitment to addressing healthcare disparities. His professional journey has seen him serve in various roles, including Public Health Educator, Teaching Support Assistant, Rural Health Coach, and President of the Redeemed Students’ Fellowship. Dr. Akinwumi is actively engaged in collaborative research efforts with experienced professionals in Public Health and related fields. His ongoing contributions involve reviewing and publishing articles in peer-reviewed journals, furthering public health initiatives’ collective understanding and advancement.

Dr. Oluwasegun Akinyemi earned his Bachelor of Medicine/Bachelor of Surgery degree at Obafemi Awolowo University in Nigeria. He then completed his residency in Obstetrics and Gynecology and became a fellow of the Nigerian Postgraduate Medical College in 2017. Dr. Akinyemi went on to earn a Master of Science in Public Health at Western Illinois University in 2020 and currently serves as a Research Associate at the Department of Surgery Outcomes Research Center, Howard University College of Medicine. With a research focus on disparities in access to quality health care for women and minority populations, Dr. Akinyemi investigates the impact of social determinants of health and chronic conditions, such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension, on health outcomes across different disciplines such as surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, internal medicine and public health in minority and immigrant communities. He is dedicated to not only identifying these disparities, but also to designing targeted intervention studies that aim to improve them. He is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Health Policy and Management at the University of Maryland School of Public Health in College Park, Maryland, USA.

Dr. Mojisola Esther Fasokun earned her Bachelor of Medicine/Bachelor of Surgery degree from Obafemi Awolowo University in Nigeria. She is recently completed a Master of Public Health with a concentration in Epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Dr. Fasokun is also gaining practical experience through her internship with the RURAL Heart and Lung Study. As a Student Research Assistant, Dr. Fasokun works at both the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s Neurology Chair Office and the Institute for Informatics (General Medicine). Her research interests center on the epidemiology of infectious and chronic diseases, as well as maternal and child health in economically disadvantaged rural communities in the United States. She focuses on risk factors such as poverty, race/ethnicity composition, and population sizes, while also striving to understand and develop interventions aimed at addressing health disparities across the country. Dr. Fasokun is eager to commence her Ph.D. program in Epidemiology.

Ejura Yetunde Salihu is a Ph.D. candidate in the Social and Administrative Sciences Division at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Pharmacy. Her research focuses on applying socio-behavioral theories and community-engaged research principles to advance health equity initiatives, particularly in disseminating and implementing culturally tailored health promotion programs for marginalized communities. Her research interests span various health and wellbeing domains, including diabetes self-management in the African American population, meditation practices to address diabetes distress in adolescents with type 1 diabetes, compassion fatigue among pharmacists, and exploring complementary and alternative therapies for college students. Before pursuing her academic journey in the United States, Ejura earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in Anatomy from the University of Ilorin, Nigeria, and the University of Nigeria, respectively. Additionally, she holds a second master’s degree in Sociology from Western Illinois University.

Nnaemeka Agunwa MD, is a dedicated researcher who is passionate about Public Health. He is a medical doctor trained in Nigeria with more than five years of experience in patient management. He also holds a master’s degree in health sciences from Western Illinois University, where he developed a strong foundation in Public Health research. He has a wide range of interests in public health research, with a particular interest in obesity in students. He has published in peer-reviewed journals, contributing valuable insights to Public Health. He has worked on numerous projects and collaborations, demonstrating a deep understanding of Public Health research. As a researcher, he has continued to explore new avenues of inquiry and remain committed to pushing the boundaries of knowledge in Public Health.

Heriberto Urby is a seasoned professional with a diverse educational background and extensive experience in Emergency Management and research. He is a professor in the School of Law Enforcement and Justice Administration at Western Illinois University, where he has been an integral part of the academic community since 2011. Dr. Urby holds a Juris Doctor (J.D.) degree from Texas Southern University Thurgood Marshall School of Law in Houston and a Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) degree from the University of North Texas in Denton. He also holds two master’s degrees, one in Business Administration (M.B.A.) and another in Education (M.Ed), along with a bachelor’s degree (B.A.).

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()