Eger W, Talbert-Slagler K, Allen H. Using an evidence-based framework to guide the implementation of syringe services programs in Jackson, Mississippi. HPHR. 2022;50. 10.54111/0001/WW3

The opioid epidemic in the United States (U.S.) has been coupled with increases in blood-borne infections, including viral hepatitis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which can be spread through injection drug use. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) recommends syringe services programs (SSPs) as an evidence-based intervention to address the spread of infectious diseases and to link people who inject drugs (PWID) to appropriate care. Jackson, Mississippi, has one of the highest HIV infection rates in the U.S., yet the city is the only urban area among the top ten incident areas for HIV infections that does not have a sanctioned SSP. The Mississippi State Legislature can request an ‘at-risk’ designation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), granting them power and funding to establish a SSP to help address increasing blood-borne infections among populations of people who inject drugs. This evidence-based commentary follows the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to outline the necessary steps and implementation challenges toward the development of a SSP in Jackson, Mississippi. This framework-based analysis revealed that SSPs have few weaknesses and carry many strengths: SSPs are adaptable, cost-effective, and beneficial for individuals and communities engaged with the programs. SSP development does come with complex political and legal obstacles that have to be untangled, particularly in states like Mississippi, where syringes are classified as drug paraphernalia. In addition to revising laws relating to syringe exchange, implementation of a SSP in Jackson must be accompanied by a grassroots, broad-based marketing and communication campaign led by public health experts who can discuss the benefits of SSPs and combat stigma surrounding injection drug use.

The HIV epidemic in the United States (U.S.) is coupled with an equally devastating syndemic of substance use disorder, one of which includes opioid use disorder (OUD). In 2020 alone, over 40 million people aged 12 or older had a substance use disorder, and 800,000 had injected heroin.1 Although HIV incidence has decreased nationally over the last two decades, annual infections have increased among people who inject drugs (PWID).2 In addition to infection-related comorbidities, such as hepatitis C virus (HCV) and HIV, PWID are at risk of morbidity and mortality from drug overdose, which has reached new heights since the COVID-19 pandemic.3-5 Though the incidence of HIV is decreasing overall, its decline has not been equal across the geographic regions of the U.S.2,6 For example, just seven southern states account for more than 50% of incident HIV infections nationwide.7 To accelerate HIV prevention progress and direct funds to these states and other HIV “hotspots,” the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has established the initiative “Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America.”7 The program seeks to reduce new infections by 90% over the coming decade through a variety of strategies, including increased access to HIV treatment and care, as well as harm reduction. Harm reduction refers to programs and policies that seek to mitigate the negative health, environmental, social, and legal impacts often associated with drug use.8

Syringe services programs (SSPs) are just one evidence-based harm reduction intervention supported by the HHS to address the overdose crisis and HIV epidemic in the U.S.9 Since the 1980s, approximately 300 sanctioned SSPs have opened in over 40 states.10 SSPs are particularly effective at decreasing injection drug use (IDU)-related infections and adverse health outcomes among PWID, yet three states on the HHS priority list for ending the HIV epidemic do not have a single sanctioned SSP: Alabama, Mississippi, and Oklahoma.7,10 Jackson, Mississippi is the only urban area within these three states that ranks in the ten highest HIV incident areas in the country, according to the CDC.6 Despite the impact of IDU in its communities, Jackson has not implemented a single sanctioned SSP, nor has the state requested an at-risk designation from the CDC for assistance.11 An at-risk designation would give Mississippi legislature the power and funding to combat the HIV and overdose crises by establishing SSPs throughout the state, particularly in high-risk areas like Jackson.

Jackson serves as an appropriate launching point for developing a robust SSP network in Mississippi because of its political climate and proximity to public health and healthcare infrastructure. Jackson, Mississippi tends to lean Democratic and currently has a Democratic mayor (Chokwe Antar Lumumba) and Congressional Representative (Bennie Thompson). According to a 2018 national survey conducted by Johns Hopkins University, Democratic and Independent voters hold more favorable views towards harm reduction strategies, like SSPs, compared to Republican voters.12 Also, Jackson is home to the University of Mississippi Medical Center, an R1 research institute, and the state’s Department of Health, which could both serve as conduits of information and provide vital resources. The development of a SSP in Jackson would set a precedent in Mississippi for the development of other SSPs statewide and potentially decrease the burden of infection- and overdose-related deaths among PWID while saving the federal, state, and local government millions of dollars in the process.13,14

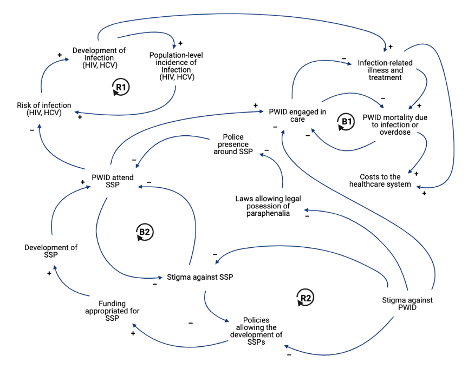

Figure 1. Causal loop diagram to describe the complex system in which Syringe Services Programs (SSPs) may be implemented in Jackson, Mississippi.

Abbreviations. SSP = syringe services program; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; HCV = hepatitis C virus; PWID = people who inject drugs; B = balancing loop; R = reinforcing loop.

Note. This causal loop diagram shows two reinforcing feedback structures (R1 and R2) and two balancing feedback structures (B1 and B2) that represent the systems at play in regards to stigmatization and politicization of SSPs, as well as morbidity and mortality caused by infectious disease and overdose among PWID. Positively associated connections (+) indicate variables that change in the same direction; negatively associated connections (–) indicate variables that change in the opposite direction.38

As defined by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), context is “the set of circumstances or unique factors that surround a particular implementation effort.”15 The decision discussed in this paper, to implement a SSP and request an at-risk designation from the CDC, is taking place in Jackson, Mississippi. As implied by Figure 1, this is a highly complex and political decision, as Mississippi remains just one of ten states in the U.S. that does not have a sanctioned SSP.10

Two significant barriers to the implementation of SSPs are stigmatization of drug use and laws prohibiting the possession of drug paraphernalia, such as syringes.11,16-19 Mississippi does not currently have laws allowing the possession of drug paraphernalia, likely exacerbating stigma around the issue of drug use at the structural, social, and internal levels.11 Structural stigma, or policies and procedures that increase the occurrence of negative attitudes towards PWID, often stem from discrimination within government, healthcare, and legal systems that lead to negative media portrayal of PWID. When people see this type of messaging in the media, there’s also the development of two other forms of stigma: socialized and internalized stigma. Socialized stigma, or recurring negative messages and communications about PWID, are often manifested in stereotyping and prejudice; and, internalized stigma occurs when an individual who uses drugs internalizes these negative messages and attitudes to themselves.20 Stigma against PWID creates a negative reinforcing loop with the stigma against SSPs and policies allowing the development of SSPs.17-19 Hence, as stigma against PWID increases, so does stigma against SSPs, which leads to a decreased likelihood of policy development in favor of SSPs.

Additionally, as structural stigma becomes more common, laws allowing for the legal possession of paraphernalia also become less likely to be passed, while the inverse is true. If policies and laws allowing for the development of SSPs and the possession of paraphernalia are implemented, there is an increased likelihood of funding (and thereby development) for SSPs and PWID using the SSPs.11,19 The more PWID that use the developed SSPs, the higher the possibility that stigmatization of SSPs within society will decrease and the more PWID will use them.11,19 The utilization of SSPs by PWID have a myriad of positive downstream effects, as highlighted throughout this paper. As more PWID attend the SSP and exchange syringes or engage in less injection-related risk behaviors, the less likely the transmission of HIV and co-infections, such as HCV.21 SSPs also play a critical role in connecting PWID to care and decreasing the likelihood of injection-related illness and mortality (such as injection-related infections and overdose).21 Left unchecked, these issues will incur substantial costs to the health care system.

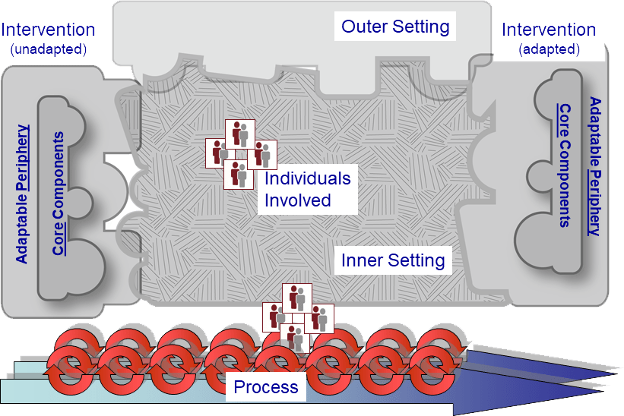

An evidence-based approach to the implementation of SSPs in Jackson, Mississippi, should follow the CFIR framework.15 As outlined in Figure 2, CFIR is composed of five overarching constructs: intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of individuals, and the process of implementation. Each construct is composed of several unique subdomains, including but not limited to: evidence, relative advantage, peer pressure, readiness, self-efficacy, and planning. In Table 1, a detailed overview of the relevant literature is used to explain the relevance of each corresponding subdomain to the implementation of interest. Utilizing an evidence-based framework for the implementation of SSPs allows for better identification of needs, an objective assessment of context, and a system for further evaluation. No such guidance is included in the existing literature, particularly with context as an essential component.22-24 A summary of the major findings noted in Table 2 is outlined below.

A SSP in Jackson would need to partner with the Mississippi Department of Health and/or the University of Mississippi Medical Center to be implemented effectively. The quality of evidence in support of SSPs reducing HIV transmission is high, while the quality of evidence is moderate in decreasing negative injection drug behaviors (such as sharing or reusing syringes) (Table 1).21 Cost-effectiveness estimates suggest that an individual SSP can save anywhere from $20,947 to $34,278 per HIV infection averted.13,14 Even in locations with controlled HIV transmission, a single SSP with a budget of $500,000 a year would only need to prevent three HIV cases per year to be cost-saving.25 These cost-savings largely come from the benefits of preventing HIV versus lifetime treatment of HIV. Overall, SSPs have a relative advantage over other programs aimed at decreasing infection risk and negative injection drug behaviors among PWID. This comparative advantage stems from the adaptability of SSPs, with the ability to adopt and withdraw programs dependent upon the needs of the community in which it is located.

However, garnering support for SSPs may be challenging due to their lack of trialability. Despite hundreds of models and even directed guidelines for developing effective SSPs, implementation of a SSP in Jackson will be complex without the appropriate policy landscape. Meanwhile, given the funding available for SSPs through the HHS, cost should not be a significant barrier. Interested localities can coordinate with the CDC to indicate that their jurisdiction is experiencing or at risk for a substantial increase in viral hepatitis infections or an HIV outbreak due to IDU.22 Although major program costs would be deferred by the federal government under this designation, costs for syringes would not; costs per syringe distributed varies from $1 to $3.26

Figure 2. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) as developed by Damschroder and colleagues.38

Notes. Intervention characteristics include the intervention source, evidence – strength and quality, relative advantage, adaptability, trialability, complexity, design – quality and packaging, and cost. The outer setting consists of patient needs and resources, cosmopolitanism, peer pressure, and external policy and incentives. The inner setting consists of structural characteristics, networks and communications, culture, implementation climate (tension for change, compatibility, relative priority, organizational incentives and rewards, goals and feedback, and learning climate), and readiness for implementation (leadership engagement, available resources, and access to information and knowledge). Characteristics of individuals involved includes knowledge and beliefs about the intervention, self-efficacy, individual stage of change, and individual identification with the organization. The process of implementation is composed of planning, engaging (opinion leaders, formally appointed internal implementation leaders, champions, external change agents), executing, and reflecting and evaluating.

Table 1. Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to evaluate institutional readiness for the implementation of syringe services programs (SSPs) in Jackson, Mississippi.

Intervention Characteristics | |

Intervention Source | Mississippi State Department of Health and/or University of Mississippi Medical Center. |

Evidence – Strength & Quality | According to a separate evaluation using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) criterion,28 evidence supporting the effectiveness of SSPs in reducing HIV transmission is high; while the quality of evidence supporting their cost-effectiveness and efficacy in decreasing negative injection drug behaviors was moderate. Moderate ratings were commonly associated with study design (non-randomized studies, cost-effectiveness analysis), indicating that evidence may be stronger than was quality-rated. Evidence behind the effectiveness of SSPs in decreasing HCV rates were mixed; however, the programs appear better than the standard of care (Supplemental Table 1). |

Relative Advantage | The Mississippi Public Health Institute conducted a qualitative report of 188 community members and key informants regarding knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about SSPs.19 The report concluded with three overarching themes: 1) SSPs and other harm reduction activities should be available for PWID; 2) Additional medical and social services are needed for people with substance abuse disorders and their families; and 3) information and education on SSPs, harm reduction activities, and infectious disease statistics should guide the state in making informed decisions for program development. Participants reported that they were interested in the concept of providing wrap-around services in SSPs that would increase entry into substance use disorder treatment and help reduce needlestick injuries. |

Adaptability | SSPs are highly adaptable; traditional SSPs have the capacity to not only exchange needles and syringes, but to provide counseling, screening, prevention, vaccination, distribution of naloxone, mental health services, physical health care, social services, and referral to coordinated substance use disorder services.21 The selection of these services can therefore be implemented and adapted depending on the needs of the local community. |

Trialability | One challenge with garnering support for SSPs is the unethical nature of running randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to test their effectiveness. Although SSPs can be individually trialed and then dismantled (a hallmark of trialability), once a participant is engaged with the SSP it is unethical to deny services for randomization purposes. Noted ethical challenges in studying PWID are concerns over whether the research evidence will be translated into practice; that the research will exacerbate background risks; and difficulties with the standard of HIV prevention research.29 |

Complexity | Complexity of implementation is evident, but decreasing. There are hundreds of models, and even directed guidelines, for the development of effective SSPs across the country.22-24 Because Mississippi does not yet have the policy landscape for allowing the implementation of SSPs, there needs to be coordination by the local and state governments. On the other hand, given the funding available for SSPs through the Department of Health and Human Services, cost should not be a major barrier; however, the provision still prohibits the use of federal funds to purchase sterile needles or syringes for the purposes of hypodermic injection of any illegal drug.7,9,22 Interested localities can coordinate with the CDC using the CDC Program Guidance for Implementing Certain Components of Syringe Services Programs to indicate that their jurisdiction is 1) experiencing, or 2) at risk for a significant increase in viral hepatitis infections or an HIV outbreak due to injection drug use.22 As reported by the Mississippi Public Health Institute, key informants and community members are accepting to the implementation of SSPs in Mississippi.19 |

Design – Quality & Packaging | Approximately 300 SSPs have been developed in over 40 states in the United States, with decades of proven models of effectiveness.10,30 SSPs are adaptive, including services from needle and syringe exchange to counseling, screening, prevention, vaccination, distribution of naloxone, mental health services, physical health care, social services, and referral to coordinated substance use disorder services.21 |

Cost | Estimates of cost vary by jurisdiction, which is dependent upon population size and geographic location.31 The average annual cost for a SSP ranges from $400,000 USD for a rural SSP (serving ~250 individuals) to $1.9 million USD for a large urban SSP (serving ~2,500 individuals). The start-up costs include 1.6% and 0.8% for small rural and large urban SSPs, respectively. Although these costs would be largely deferred by the federal government, cost per syringe distributed varies from $3 (small urban) to $1 (large rural), which is not covered by the federally funded program.22,26 Cost-effectiveness for SSPs is high; some estimates indicate that SSPs save $1,000-$3,000 for each client enrolled (on health and quality of life measure costs), while others indicate saving $20,947 per HIV infection averted.13,14 |

Outer Setting | |

Patient Needs & Resources | The Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM) indicates six elements guiding the evaluation of patient centeredness for an intervention: patient choices are provided, barriers are addressed, transition between program elements is seamless, complexity and costs are minimized, and patients have high satisfaction with the service, degree of access, and receive feedback.31 SSPs provide a multitude of additional services, such as mental health care and social services, that patients can choose to interact with.21 Meanwhile, most SSPs address barriers to access by being set in communities of greatest need; some SSP programs have even adapted to provide mobile options.32 Because most programs offered by SSPs can be incorporated into the program, transition between programs is often seamless and minimally complex; however, referral specialists may be required for larger, urban SSPs.11 Most SSPs operate on a no-cost basis, increasing accessibility,23 while acceptability remains high among PWID and community members.18,19 The largest barrier to satisfaction and access among participants are prohibitive paraphernalia laws.11,18,19 |

Cosmopolitanism | In order for a SSP to be effective, successful, and acceptable, it must be networked with other external organizations. Partnering with the University of Mississippi might be a useful mechanism for increasing cosmopolitanism. Networks are necessary for SSPs to provide holistic services where necessary, such as substance use treatment programs, mental health services, and sexually transmitted infection-based treatments.11,21,22,27,33 |

Peer pressure | The implementation of SSPs is not based in profit or individual organizational development, but in the best interest of community members and high-risk PWID. Peer pressure is not applicable to the implementation of needle exchange programs in Mississippi; however, they are one of the few remaining states in the country that have not implemented any such program.10,30 |

External Policy & Incentives | The Department of Health and Human Services and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are invested in the development of SSPs.7,9,22 Yet, there remain procedural barriers to the implementation of SSPs in Mississippi, given the lack of political will and policy landscape.11,34 Paraphernalia laws at the state level need to be restructured to allow for the effective introduction of SSPs into Jackson, Mississippi. |

Inner Setting | |

Structural Characteristics | The social architecture of SSPs are dependent upon their size and services offered.21,26 Some programs may operate with a small team of clinical staff aimed directly at syringe and needle exchange services, while other larger organizations may operate with clinical providers, mental health clinicians and psychiatrists, and research teams. Jackson, Mississippi has a population only 36,000 larger than that of New Haven, Connecticut (166,000 vs. 130,000). In 2001, estimates approximated that there were 2,000 PWID in New Haven, with 700 receiving services from the active SSP.35 New Haven’s SSP contains a clinical, administrative, and research division of approximately 25 employees. The SSP in Jackson, Mississippi will likely need to be slightly larger, with greater emphasis on programs focused on rural outreach.23 |

Networks & Communications | Similar to cosmopolitanism, SSPs will have to have well-rooted networks and connections within communities to be effective. As indicated by the National Alliance of State & Territorial AIDS Directors and the CDC, SSPs will have to build community relationships aimed at providing and linking community members to health and social services.22,23 Services provided will need to be communicated to communities of need, with extensive promotion and support from the local community.19,23 |

Culture | According to CFIR, culture is defined as relatively stable, socially constructed, and subconscious.15 Because there is no existing SSP structure in Mississippi, organizational culture will need to be established; however, community culture will have to change and adapt to decrease stigmatization and increase acceptability of the program.18,19 |

Implementation Climate | Climate, as defined by CFIR, is the localized and more tangible manifestation of the largely intangible, overarching culture; climate is a phenomenon that can vary across teams or units and is typically less stable over time compared to culture.15 Climate for the developed SSP will have to be established post-implementation. A climate of acceptance, equity, inclusion, and humility will have to be entrenched within any effective, acceptable, and successful SSP. |

Tension for Change | The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has established that the HIV and IDU situation in Mississippi is intolerable.7 In coordination with the CDC, HHS has established a program to offset the cost of the development and implementation of SSPs in priority areas, such as Mississippi, indicating their significance.21,22 Prominent researchers have recognized the significance of SSPs in decreasing the burden of disease in PWID, but Southern states have been slow to adopt harm reduction programs to curb the opioid and HIV syndemics.34 |

Compatibility | The compatibility between federal policies and Mississippi state policies do not align with the establishment of SSPs.7,9,11 Community members and stakeholders experience hesitancy with needle and syringe exchange in particular, with emphasis regarding the contradiction of law enforcement efforts to stop illegal drug use.18,19 For those stakeholders engaged in needle exchange, infectious disease surveillance, and injection drug use, SSPs are deemed a valuable and acceptable resource.19 |

Relative Priority | Implementation of SSPs is not a priority for the Mississippi State Legislature, nor those in Jackson, despite the HHS and CDC Plan for Ending the HIV Epidemic.7,9,11 Other entities, including the Mississippi State Department of Health, Center for Mississippi Health Policy, and Mississippi Public Health Institute have vested interest in the implementation of SSPs in Mississippi and have noted their benefit.11,21 In spite of a consolidated report by the aforementioned entities under the 2018 Opioid Crisis Cooperative Agreement, no public support for or progress by the state legislature has been documented in regards to the development or implementation of SSPs. |

Organizational Incentives & Rewards | SSPs funded by HHS and the CDC are subject to the terms and conditions incorporated or referenced in the recipient’s federal funding.22 As outlined by the National Alliance of State & Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD), individual SSPs should be responsible for process and outcome monitoring, as well as program quality improvement.23 Established SSPs should develop extrinsic incentives such as goal-sharing awards, performance reviews, promotions, and raises in salary as compensation to their stakeholders for quality maintenance and improvement.15 |

Goals & Feedback | As outlined by CFIR, organizations should utilize the Chronic Care Model for emphasizing the importance of relying on multiple methods of evaluation and feedback including clinical, performance, and economic evaluations and experience.15,36 |

Learning Climate | A positive learning climate should allow opportunities for team members to express input, provide assistance, feel valued, and be acknowledged as partners in the process of change. Leaders should accept advice and be willing to adapt their practices to the needs of the team and community.38 Quantitative measurement instruments are available for measuring an organization’s learning capability.15,37 |

Readiness for Implementation | Readiness for implementation is defined as the tangible and immediate indicators of organizational commitment to its decision to implement an intervention, and consists of three sub-domains: leadership engagement, available resources, and access to information and knowledge.15 Readiness is differentiated from climate in that readiness includes specific tangible and immediate indicators of organizational commitment to the decision. |

Leadership Engagement | Political leaders in Jackson, Mississippi and the southern United States are not currently engaged with the intervention.11,34 Other leaders in the field, such as the Mississippi State Department of Health, Center for Mississippi Health Policy, and the Mississippi Public Health Institute are engaged and prepared for change.11,19 Political will needs to change in order for the effective implementation of SSPs in Mississippi. |

Available Resources | Funding resources are available for the implementation of SSPs in Mississippi under the Department of HHS in coordination with the CDC.7,9,22Additional resources, such as program implementation, and monitoring guides for the development of SSPs are available from the CDC, NASTAD, and the Comer Family Foundation for support.22-24 |

Access to Information & Knowledge | Excellent work has been done to establish the policy and cultural landscape, need, and effectiveness of SSPs in Mississippi; however, little work has been done to adapt resources to local context and build an evidence-based framework for the implementation of such a program.11,19,22-24 With the help of this report and existing infrastructure developed by the CDC, NASTAD, Comer Family Foundation, and Mississippi-based resources, access to information and knowledge for the implementation of SSPs in Jackson, Mississippi is possible. |

Characteristics of Individuals | |

Knowledge & Beliefs about the Intervention | Acceptability research for SSPs is sparse, but of the available resources there are noted challenges and facilitating factors. Of the 188 key informants and community members interviewed by the Mississippi Public Health Institute, most reported acceptability of SSPs is in providing wrap-around services that would increase entry into substance use disorder treatment and help reduce needlestick injuries; however, individuals also noted hesitancy regarding the contradiction of law enforcement attempts at decreasing illicit drug use.19 Effectiveness of SSPs in decreasing needlestick injuries and infectious disease transmission is established, bolstering community support.21 Yet, political support is still a significant barrier; without the overhaul of paraphernalia laws at the state and federal level, negative beliefs about SSPs will continue to remain a challenge.11,19,34 |

Self-Efficacy | SSPs provide PWID the opportunity to take control of their health and treatment through referrals to medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD), mental health services, and physical health care.21 New users of SSPs are five times more likely to enter drug treatment and three times more likely to stop using drugs than those who don’t engage in needle exchange services.38 Given the appropriate information, such as that outlined in this report, political self-efficacy may change; the more confident the political leaders are in their ability to make the changes necessary to achieve the implementation goals, the higher their self-efficacy.15 Individuals with high self-efficacy are more likely to embrace the intervention and exhibit committed use even in the face of obstacles. |

Individual Stage of Change | According to the trans-theoretical model, the stages of change are pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance.39 To overcome the largest barrier to SSP implementation in Jackson, Mississippi, political leaders must move from pre-contemplation to action and maintenance. Slow adoption of SSPs in the southern United States has been observed, but not absent.50 The Mississippi State Department of Health, Department of HHS, and the CDC are prepared to assist the Mississippi State Legislature through this process, but advocacy and evidence must be brought to their attention.7,9,11,23 |

Individual Identification with Organization | Guided discussion groups included in the Mississippi Public Health Institute’s report “Syringe Services Programs in Mississippi: Assessment of Knowledge, Attitudes & Beliefs of Communities & Key Informants” unanimously indicated that there was an opioid and drug crisis in their communities.19 Given the prolific nature of the opioid and HIV epidemics, identification with drug use and the services provided by traditional SSPs are widespread. |

Process of Implementation | |

Planning | Planning, as defined by CFIR, attempts to design a course of action to promote the effective implementation of an intervention by building capacity for using the intervention.15 Prior to the implementation of a SSP in Jackson, Mississippi, laws relating to syringe exchange need to change. The state or locality has to allow syringe exchange and exemption of syringes from the classification of drug paraphernalia.11 Currently, Mississippi law does not authorize the exchange of syringes and categorizes syringes as drug paraphernalia. Upon the change in laws, the state legislature in accordance with the Mississippi Department of Health must declare that their jurisdiction is 1) experiencing, or 2) at risk for a significant increase in viral hepatitis infections or an HIV outbreak due to injection drug use to the CDC and HHS.22 As Mississippi is one of seven states included among those with substantial HIV burden by the HHS, the designation should not be contentious.7,9 Implementation of individual SSPs may be developed in accordance with the guidelines set by the CDC, NASTAD, and the Comer Family Foundation, as described elsewhere.22-24 The contextual factors and services outlined in this report should be taken into account for implementation purposes, adapted to the local Jackson community. One analogy made by the Mississippi Public Health Institute that was highly effective in garnering support or changing negative ideologies associated with syringe services was “contraception distribution programs to teens… expressing that those programs did not promote or increase sexual activity.”19 |

Engaging | Engaging involves attracting and involving individuals in the implementation through a combined strategy of social marketing, education, role modeling, training, and other activities.15 |

Opinion Leaders | There are two types of opinion leaders: experts and peers.15 Expert opinion leaders in Jackson, Mississippi essential to the implementation of the intervention are Congressional Representative Bennie Thompson, Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba, and State Health Officer Dr. Thomas Dobbs (or his replacement). |

Formally Appointed Internal Implementation Leaders | Formally appointed internal implementation leaders are individuals from within an organization who have been formally appointed with the responsibility for implementation of an intervention.15 Internal implementation leaders should include a diverse cast of community-based stakeholders and experts knowledgeable in the prevention of drug use and infectious disease. |

Champions | Champions should include individuals that are dedicated to the marketing and support of an intervention; they would be distinct from opinion leaders in that they actively associate themselves with support of the intervention during implementation.15 Champions can include PWID, clinical providers, and other various stakeholders that have a vested interest in seeing the implementation of a SSP in Jackson, Mississippi. |

External Change Agents | External change agents are typically individuals who are affiliated with an outside entity who formally influence implementation of an intervention in a positive direction.15 External change agents in this case can be technical experts from the Mississippi Public Health Institute, Center for Mississippi Health Policy, Mississippi Department of Health, or University of Mississippi Medical Center. |

Executing | Execution of the intervention should attempt to maintain fidelity, intensity, timeliness, and degree of engagement with key stakeholders (e.g., implementation leaders).15 Execution is difficult to assess but should be considered and evaluated throughout the implementation process. |

Reflecting & Evaluating | Reflecting and evaluating on the implementation of the intervention should be conducted through qualitative and quantitative mechanisms.15 Objectives should also be specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and timely, according to the SMART rubric.15,40 Upon reflection and evaluation, individually established SSPs can use guidelines as developed by the CDC, NASTAD, and the Comer Family Foundation to set goals and evaluation standards.22-24 For example, according to the CDC’s Program Guidance for Implementing Certain Components of Syringe Services Programs, it would be valuable for programs to monitor the provision of sterile needles, syringes, and other drug preparation equipment; and the provision of condoms and HIV, viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted infection, and tuberculosis screening tests; among other items and programs.23 |

Supplemental Table 1. Rating the quality of evidence for Syringe Service Programs (SSPs) through the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) criterion.a,28

Quality Assessment | Quality Rating | ||||||

No. of Studies | Study Design | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerationsb |

|

Outcome: HCV prevalence | |||||||

6 | Non-Randomized Studies | Not serious | Neither serious nor not serious | Neither serious nor not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Low |

Outcome: HIV prevalence/incidence | |||||||

12 | Non-Randomized Studies c | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | High |

Outcome: Injection Drug Behaviors | |||||||

5 | Non-Randomized Studies | Neither serious nor not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Neither serious nor not serious | Moderate |

Outcome: Cost-effectiveness of Syringe Services Programs | |||||||

3 | Decision-analyses | Neither serious nor not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate |

a GRADE evaluation was conducted separately from this paper.

b Other considerations included publication bias, large effect sizes, plausible confounding, and the dose response gradient.

c One study included in the systematic review was a quasi-randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Acceptability of SSPs is high among PWID and community members in Mississippi and the U.S. Highlighted successes of SSPs include the program’s flexibility, streamlining of needs, and no-cost services.18,19,23 The most significant barrier to satisfaction and access among participants are prohibitive paraphernalia laws.11,18,19 To enable the success of a SSP in Jackson, a network of community partners will be necessary, including partnerships with the University of Mississippi or community-based organizations working in the areas of substance use or mental health, among others.27

The social architecture of SSPs are dependent upon their size and services offered. Some programs may operate with a small team of clinical staff aimed directly at syringe and needle exchange services. In contrast, other larger organizations may operate with clinical providers, mental health clinicians, and research teams.21,26 The SSP in Jackson will likely need upwards of 30 employees, with an emphasis on programs focused in rural outreach.23 In addition to networks grounded in community partnerships, the services provided by the SSP will need to be clearly communicated to communities in need.19,23 For this to be accomplished, community culture will have to adapt to decrease the stigmatization of SSPs; which includes a climate of acceptance, equity, and inclusion.18,19 In conjunction with a new climate, political and legal policies must align with the program’s goals. For those stakeholders engaged in needle exchange, infectious disease surveillance, and IDU, SSPs are deemed a valuable and acceptable resource; however, SSP implementation does not appear to be a priority for Mississippi State Legislature or those in Jackson at this time.11,19

To promote the development of a SSP in Jackson, any such SSP should be responsible for process and outcome monitoring, which could then be used as evidence to garner further support for the program.15 Ultimately, policymakers in Jackson and throughout the state need to change political will for effective implementation. Other leaders in the field, such as the Mississippi State Department of Health, Center for Mississippi Health Policy, and Mississippi Public Health Institute, can be used as change agents.11,19 Although excellent work has been done to establish the policy and cultural landscape, need, and effectiveness of SSPs in Mississippi, little work has been done to adapt resources to the local context and build an evidence-based framework for the implementation of such a program.11,19,22-24 With the help of this report and existing infrastructure, access to information and knowledge needed for the implementation of SSPs in Jackson is possible.

According to the Mississippi Public Health Institute’s report on SSPs in Mississippi,19 SSPs are widely viewed as acceptable in providing wrap-around services that increase entry into substance use disorder treatment and help to reduce needlestick injuries. Respondents also noted hesitancy regarding the contradiction of law enforcement attempts at decreasing illicit drug use.19 Harm reduction programs, like SSPs, allow PWID to take control of their health and treatment through referrals to medication-assisted treatment for OUD, mental health services, and physical health care.23 In the meantime, given the appropriate information, political self-efficacy may change. Considering the nature of the opioid and HIV epidemics, knowledge of the issues has the potential to be used to leverage support for SSP development in Jackson.

. Prior to implementing a SSP in Mississippi, laws relating to syringe exchange need to change. The state or locality has to allow syringe exchange and the exemption of syringes from the classification of drug paraphernalia.11 Upon the change in laws, the state legislature, in accordance with the Mississippi Department of Health, must declare that their jurisdiction is experiencing or is at risk for a significant increase in viral hepatitis infections or an HIV outbreak due to IDU.22 Implementation of individual SSPs may be developed in accordance with the guidelines set by the CDC, National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD), and the Comer Family Foundation.22-24 The contextual factors and services outlined in this report should be considered for implementation purposes and adapted to the local Jackson community. For the appropriate process to be undertaken, opinion leaders – such as Congressional Representative Bennie Thompson, Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba, and State Health Officer Dr. Thomas Dobbs (or his replacement) – including formally appointed internal implementation leaders, champions, and external change agents need to be identified and engaged. In time, these factors should coalesce in the opportunity for execution of the intervention, which should attempt to maintain fidelity, intensity, timeliness, and a strong degree of engagement with stakeholders. Upon implementation, reflection and evaluation of the intervention should be conducted to ensure standards and set future goals.15,22-24

SSPs are a beneficial and cost-effective public health intervention plagued by political and legal challenges that significantly impact their implementation. Not only are SSPs effective at decreasing HIV transmission and negative injection-related behaviors (such as needle sharing), but they also help connect individuals who use drugs to needed services. SSPs provide an avenue for PWID to seek help with psychiatric care, employment counseling, substance use treatment, and other important social determinants of health. With the development of over 300 SSPs around the country, there is strong evidence to suggest that the development of a SSP in Jackson would save lives and tax-payer dollars. Given the proper education and knowledge, community coalitions can be built to sustain a SSP in even the most hesitant of communities.

This framework-based analysis shows that SSPs carry many strengths. They are highly adaptable, cost-effective, and beneficial for those engaged with the program and the surrounding community. The more we can decrease community transmission of HIV and its co-infections, the healthier our communities will become. SSP development also comes with complex political and legal obstacles that have to be untangled, especially in the case of Mississippi, where drug paraphernalia laws are still in place. Despite the growing opioid epidemic and overdose crisis, there seems to be little political will to tackle the present issue. If a coalition of changemakers were to apply the information used in this report to garner change in their communities and local legislature, the development of a SSP in Jackson might not be too far afield. Implementing a SSP must be accompanied by a grassroots, broad-based marketing and communication campaign that discusses the cost-effective, adaptable, and safe nature of SSPs. Plans for implementation must include language expressing the connection to substance use treatment and other services while assuring communities that SSPs are known to decrease negative injection drug-related behaviors, such as needle sharing and reuse. Public health experts in Mississippi need to take charge and lobby for change, given the tremendous evidence in support of SSPs. Without doing so, more unnecessary preventable deaths and morbidity will be attributed to overdose, infection, and unwarranted stigmatization. The Mississippi State Legislature and the Mississippi Department of Health must declare an at-risk designation with the CDC to obtain the necessary resources to establish a SSP in Jackson.

The authors have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

The authors would like the thank the Yale School of Public Health, Yale Institute for Global Health, and University of Mississippi School of Applied Sciences for making this collaboration possible.

Will Eger, MPH is a Postgraduate Research Associate at the Yale University School of Medicine, Section of Infectious Diseases, AIDS Program. Will’s primary research focuses on social vulnerability and infectious diseases using mixed methods and implementation science techniques. He has worked on several domestic and international projects related to the social determinants of health with a particular interest in HIV and other emerging and re-emerging infections. Will received his master’s degree from the Yale School of Public Health in Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Global Health in May 2021. Starting Fall of 2022, he will be attending a Joint Doctoral Program (Ph.D.) in Interdisciplinary Research on Substance Use at the University of California San Diego and San Diego State University pursuing research related to HIV and comorbidity prevention among people who inject drugs.

Dr. Talbert-Slagle is an Assistant Professor of General Internal Medicine at the Yale School of Medicine, a Core Faculty member at the Equity Research and Innovation Center, and an Associate Director at the Yale Institute for Global Health. She is a global health scholar and educator, focused on addressing global health and educational disparities through high-quality, interactive teaching and locally-appropriate and responsive scholarship and field programs. With doctoral training in genetics and virology and postdoctoral training in complex systems and global health management, Dr. Talbert-Slagle approaches her work, teaching, and mentorship through an interdisciplinary perspective. Dr. Talbert-Slagle received her B.S. and B.A. degrees from the University of Kentucky and her Ph.D. from Yale University.

Dr. Hannah Allen is an Assistant Professor in the Health, Exercise Science, and Recreation Management department at the University of Mississippi and the director of the Substance Use & Mental Health Research Lab. Her research is broadly focused on substance use in a developmental context, examining the relationship between substance use and both mental health and achievement throughout college and young adulthood. Dr. Allen received her Ph.D. in Public Health from the University of Maryland and completed a NIDA-funded postdoctoral fellowship at Penn State University.

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()