Efendić I, Ahmetagić I, Srabović N, Mujanović A, Sivić S, Smajić R, Mihajlović S, Mahmuzić E, Omerović M, Begić E, Šadić A, Ahmetspahić E, Efendić I . Attitudes and Knowledge Towards Immunization in Tuzla Canton Population. HPHR. 2021; 31.

DOI:10.54111/0001/EE15

Introduction: Despite the proven safety and efficacy of vaccines, common diseases which can be prevented

by regular vaccination, are still not controlled in all European countries. The most important barriers which

parents encounter while making decisions about vaccination include unwanted vaccination effects, attitude

towards the disease, and the effectiveness and safety of the vaccine.

Methods: The sample consisted of 1850 participants who have registered place of residence in one of the five

cities in the region of the Tuzla Canton. The questioner was created by the authors of this paper and it consisted

of 22 items which were divided into 4 categories.

Results: Statistical analysis showed that more than half of participants who have declared themselves as

vaccine skeptics had completed secondary school as their last level of education, and base their attitude on the

information provided through the mass media sources without performing additional verification. It has been

found that there is a certain percentage of healthcare workers with whom the parents contacted, and who

advised them against the immunization of their child, which further deepens the skepticism of parents.

Discussion: We need better and more efficient ways of informing and engaging the vaccine sceptic parents.

This whole process cannot be left to the parents themselves, and the role of a healthcare professional is based

on the fact that he/she is a reference person who will inform, through adequate communication, provide basic

knowledge and help the parents during this entire process.

Key Words: vaccine, active immunization, MMR vaccine, anti-vaccination movement

First protests against vaccination have appeared with the development of modern immunology in the 18th

century,1 and they have changed little over time.2 Historically, protests have always included an emotional

component, emphasizing parental commitment, condemning microorganism theories, accusing physicians for

manipulation and alternative data analysis. Educational campaigns which advocate for vaccination can often

portray those who are in the opposition as poorly informed, overly emotional or irrational, which antagonizes

the group of those who express their skepticism towards vaccines even further more. The presence of current

social and political tensions show that these protests have endured over time.3 Before, disagreements have

mostly revolved around civil rights and distrust for those in positions of power. Although these arguments are

still in force, the current focus has been shifted towards criticism of medicine, science and authority of doctors

themselves.

Despite the proven safety and efficacy of vaccines, common diseases which could be prevented by them,

such as measles and varicella, are still not controlled in all the European countries.4 Guides and major

barriers for parents in decision-making process about vaccination have been studied. The most important

predictors include the perception of the disease-related risks and adverse vaccination effects,5 their attitude

towards the illness,6 and the effectiveness and safety of the vaccine against the disease.7 In addition, religious

beliefs, and the growth of alternative medical techniques, have been recorded as key deciding factors as

well.8 Information which are at the pediatrician’s disposal and the doctors communication style during the

vaccination process can also influence the parents decision.9, 10

Some parents perceive a small threat and possibility of illness, ironically, because of the previous successes

of vaccines in reducing the incidence of those particular diseases,2 while other parents explicitly say that the

vaccine itself is more dangerous than the disease which the vaccine protects against.10 With some parents, a

psychological phenomenon of “cognitive bias” is perceived, where parents would feel worse if their child was

injured due to their action (getting a vaccine), than by the absence of their action (not receiving one), which is

why they opt for the latter.11

Vaccination programs vary greatly across Europe, from highly centralized to fully decentralized systems. Both

have advantages and disadvantages. System harmonization in this area is neither a prerequisite nor a

guarantee of success.12

The sample consisted of 1850 randomized participants. The only including criteria was a place of permanent

residency in one of the five municipalities in the Tuzla canton region including: Tuzla, Lukavac, Živinice,

Gračanica and Gradačac, as well as the current or expected status of an individual, finding themselves in the

role of a parent. Excluding criteria were all affected psychological and somatic states, which could contribute

to the unwillingness or the inability of participants to completely and independently fulfil the entire questioner.

The questioner was created by the authors of this paper for a specific use in this study. All of the participants

were informed why were they taking the poll and what will the results be used for. The survey was anonymous

and voluntary, meaning no one was forced to fill it against their will. The questionnaire consisted of 22 items

which were divided into 4 categories: (i) demographic and socio-epidemiological data of the participant (5

items); (ii) general knowledge and personal attitude about vaccination (7 items); (iii) information source about

vaccines and vaccination related topics (6 items); (iv) and their level of critical thinking in regards to these

topics (4 items).

Most questions in this survey were closed-question types, and more than half of those were proposed in

Yes/No format. Other questions were formatted as a multiple-answer types of questions. Exception was made

for two open-type questions in the category regarding general knowledge and personal attitude of the

participants about this topic. The questioner was distributed at the beginning of February 2018. and was

conducted over the course of two months. All the data checking and entry was done into a pre-developed

database via MedCalc statistical software, by the paper authors.

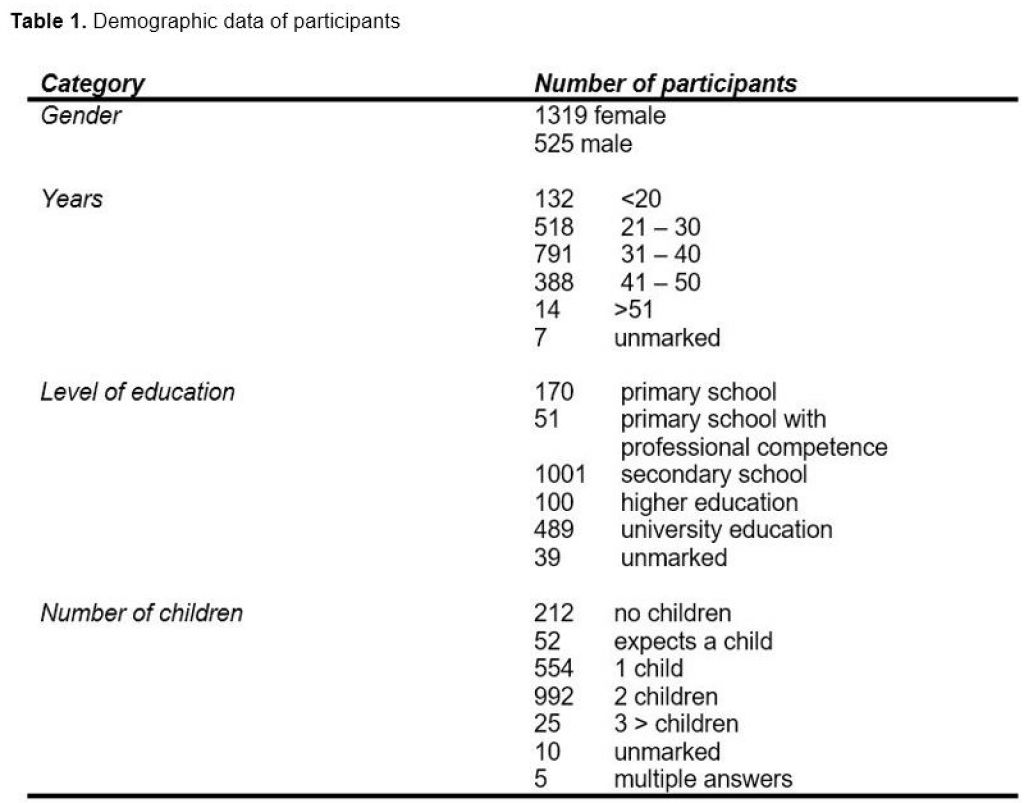

A total of 2,000 questionnaires were printed, and 1850 of them were returned filled-out, giving a response rate

of 92.5%. The average responder was a mother, aged between 31 and 40, with two children. As far as

education is concerned, just over half of the respondents had secondary education as their last completed

level of education. Demographic data is summarized in Table 1.

Testing the difference between the total sample of 1850 and the vaccine skeptics, according to their

educational level, X2 test found that there was a statistical significance (X2 = 30.801, p <0.05). The most

significant difference was found on the university level of education, where this group was significantly present

higher in the sample of 1850, rather than in the vaccine skeptic group. In relation to this, in the group of

vaccine skeptics, 63% of the respondents opted for high school as their last achieved level of education

(Figure 1).

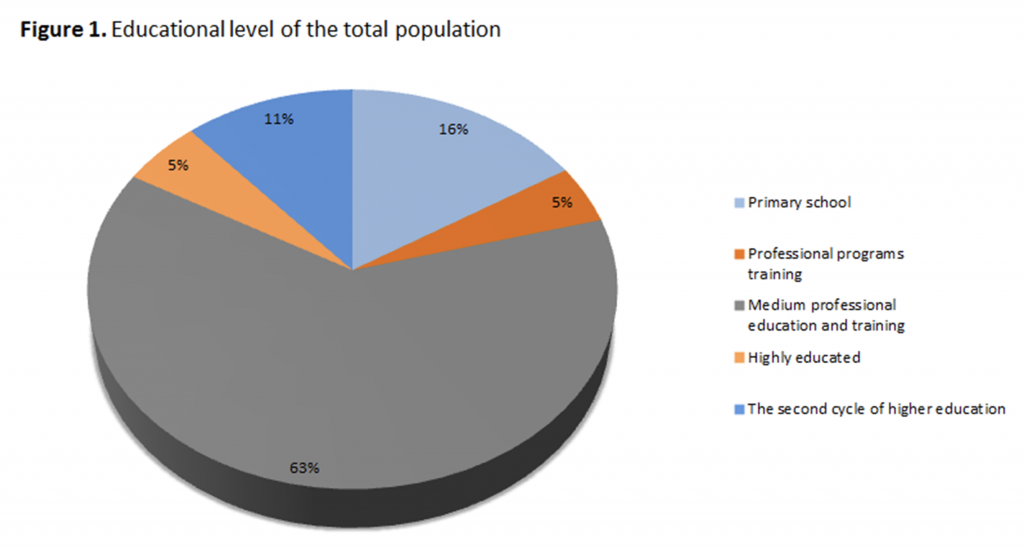

During testing the difference between the total sample and the vaccine sceptics according to the number of

children, with the X2 test, we have found that there was a statistical significance (X2 = 199.071, p <0.05). The

most significant difference in the number of children, is in the group of parents who have declared themselves

against vaccination, where there is a significantly higher percentage of those who do not have children at all

(Figure 2).

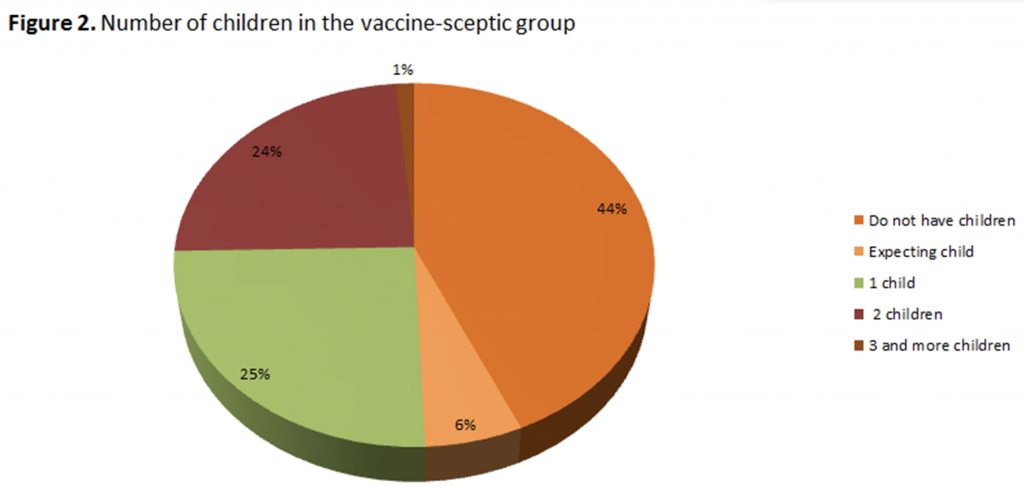

Half of the participants listed several of the most common diseases against which there are vaccines,

however, also the other half of the examinees were unable to identify either one disease against which

vaccine immunization programs exist. Chart 3 shows the total number of respondents who were generally

opposed to vaccines (n = 151), where it was found that 82% of them could not name any diseases which

could be prevented through vaccination programs (Figure 3).

Between the total number of parents and parents who have declared themselves as vaccine-sceptics, when

we analyzed their children’s vaccine status, X2 test found that there was a statistical significance (X2 =

270.703, p <0.05). There were significantly less vaccinated in the vaccine sceptic group. All parents who

declare that they were against vaccination (n = 151) did not regularly vaccinate their children.

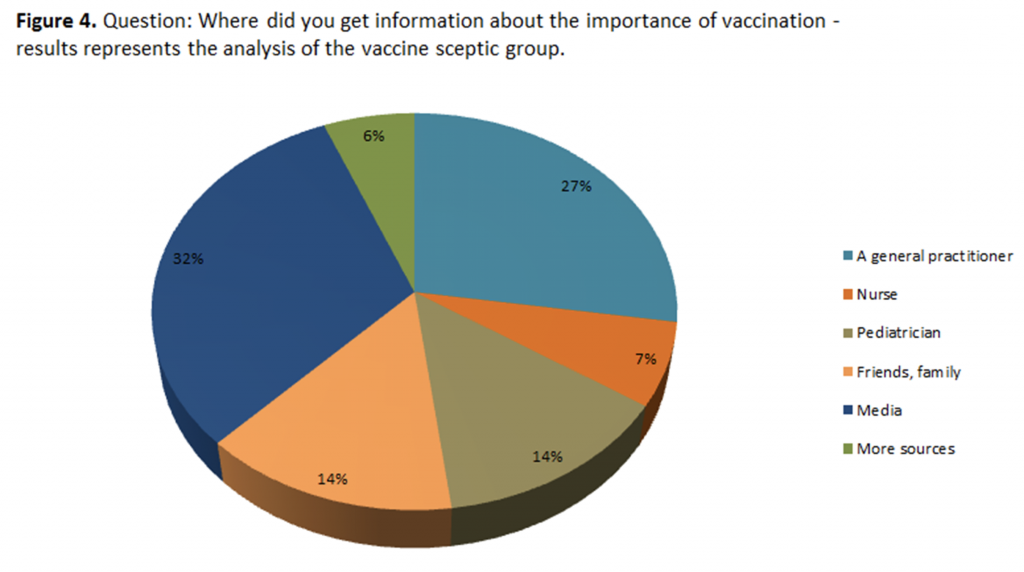

When it comes to information sources which the parents use, to inform themselves about the importance of

vaccination, the X2 test found that there was a statistically significant difference between the two groups of

parents (X2 = 94.823, p <0.05). The 1850 group receives most of their information from a pediatrician, while

the group of vaccine sceptics receives significantly more information from the media, as shown in Figure 4.

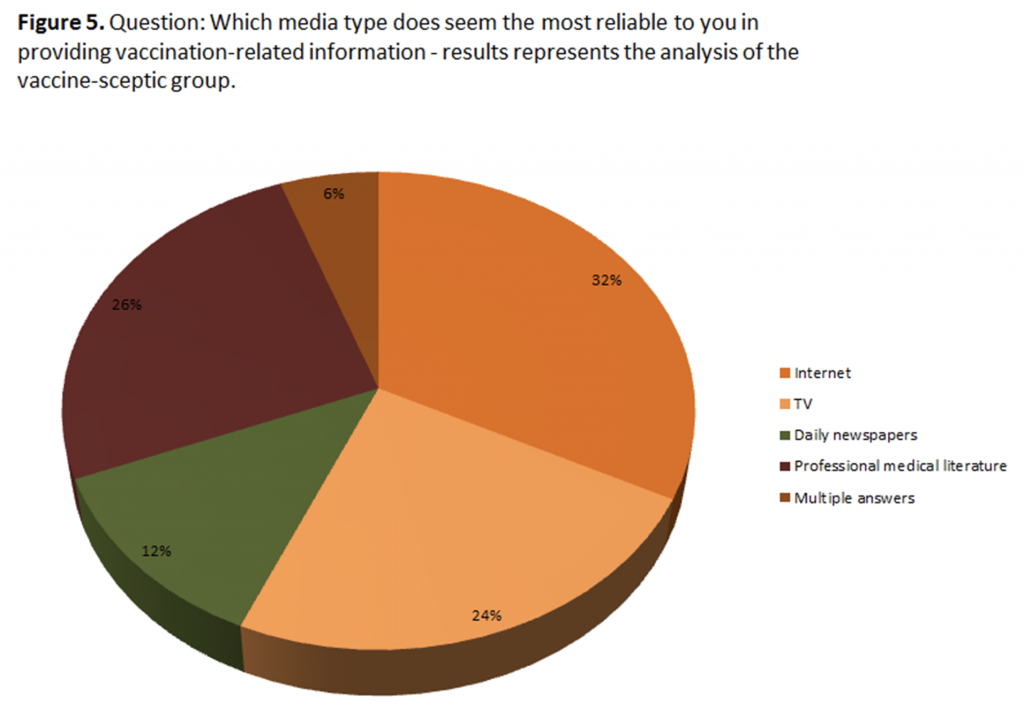

When asked which type of information source do they consider the most reliable, the majority of respondents

(n = 1053) opted for the option of professional medical literature; second one was the internet (n = 325), then

TV (n = 263) and other mass media sources. Noteworthy is the fact that almost one third of participants who

have been declared as vaccine sceptics (n = 47) use the media as the most reliable mean of informing

themselves on this topic. Figure 5 shows the total score

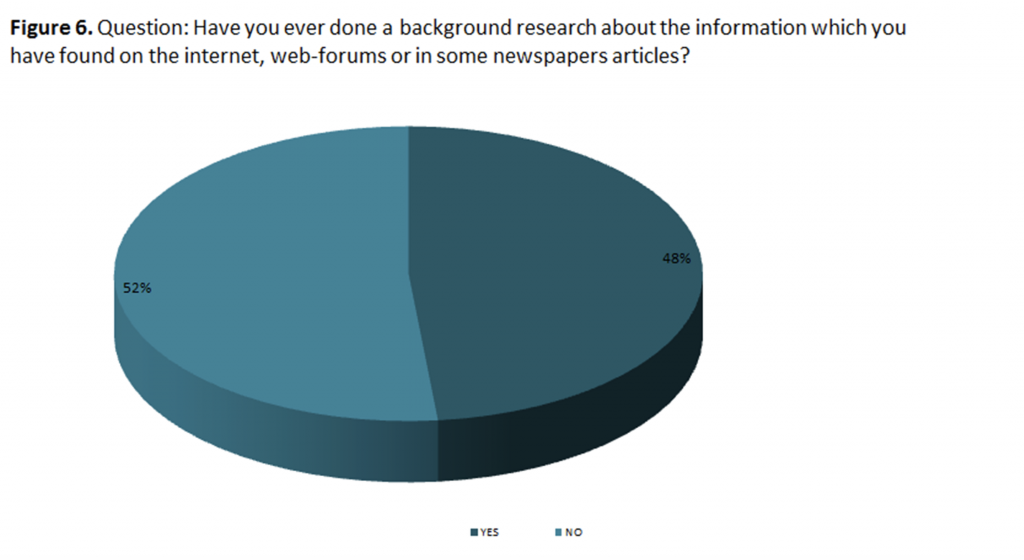

We found that there is a statistically significant difference in the verification of information written in the media

between the two groups (X2 = 169.995, p <0.05). The worrying fact is that 48% of the vaccine skeptic do not

perform additional verifications of information found on internet portals, forums or newspaper articles (Figure

6).

Those who use internet to search for vaccine-related topics, using the simplest terms, will most likely end up

on sites which are oriented against vaccinations (Kata A, 2010). And because of this information, 18% of our

study participants, or more than 300 parents, changed their decision to vaccinate their own child / children.

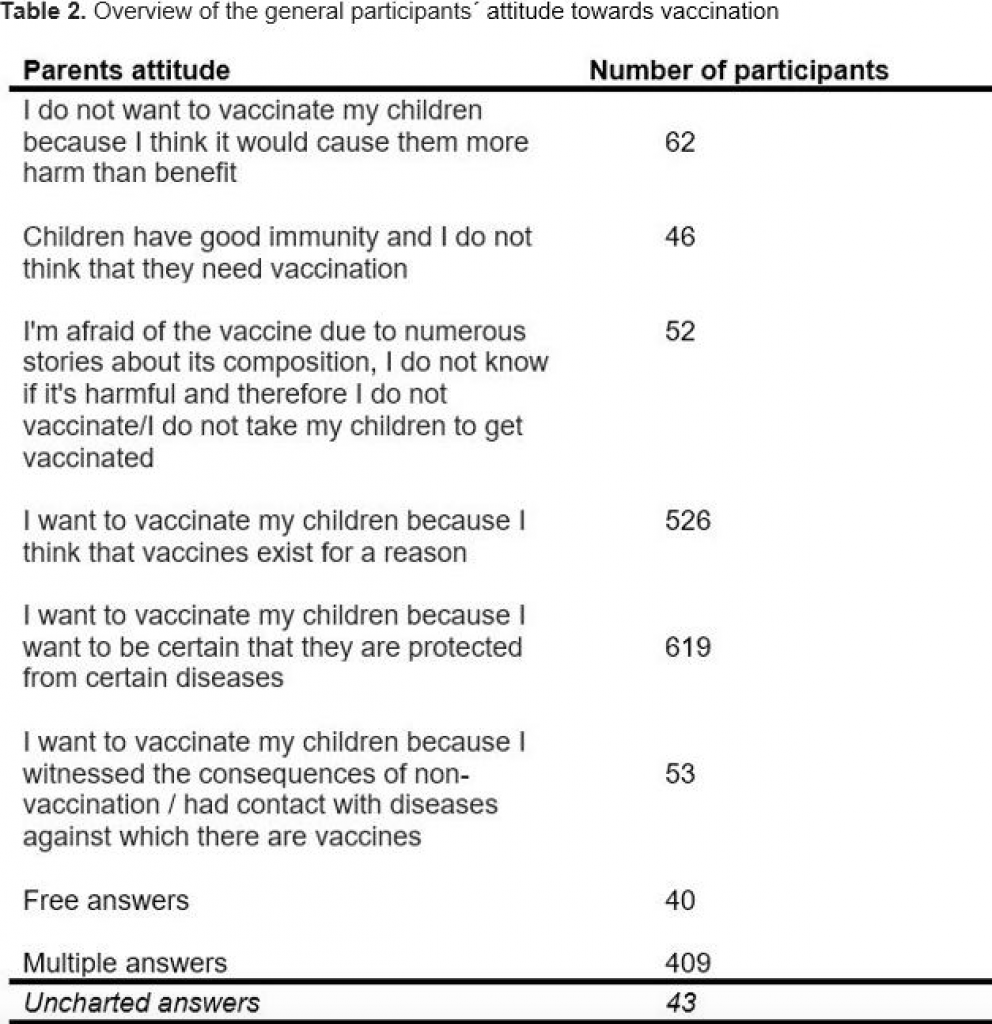

When asked about their general attitude towards vaccination, the results were quite different and according to

Table 2.

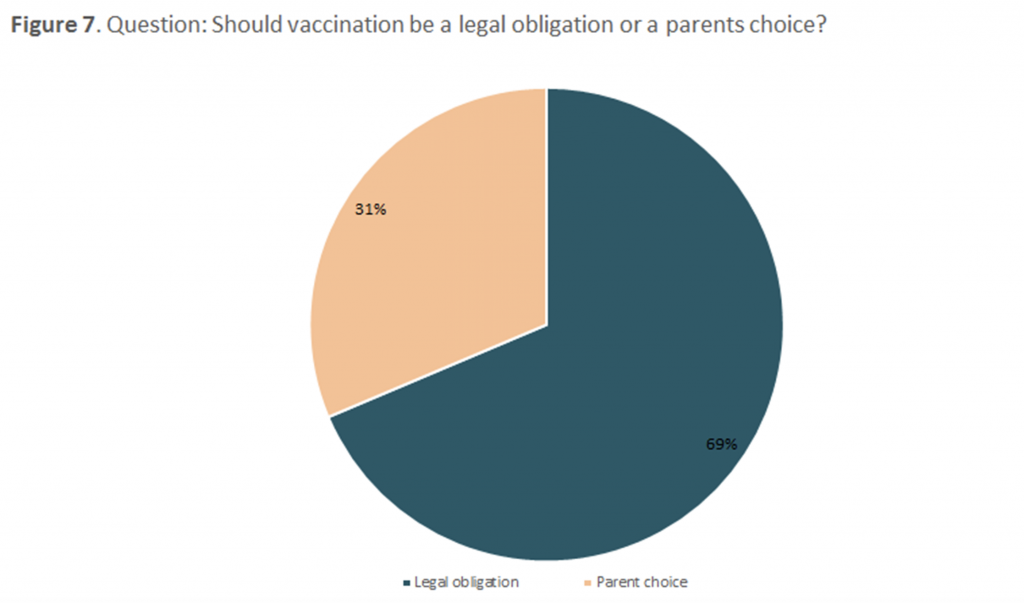

Finally, we wanted to explore the opinions about the decision-making process on the vaccination of children,

more precisely if it should be a legal commitment or just a necessity. The majority of participants (69%)

decided that this should be a legally binding decision, as opposed to 31% of parents who declare that they

should be the only ones who have a word in the immunization process of their own child (Figure 7).

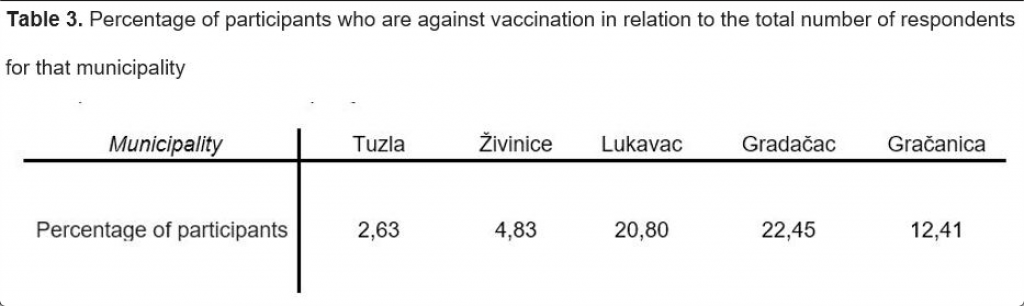

We also wanted to check whether there are health workers who advised against vaccination. We found that

10% of health workers with whom parents have come into contact with, counseled them against the

immunization of their child/children. The percentage of parents who declare themselves as vaccine skeptics

varies from municipality to municipality, as shown in Table 3.

Paradoxically, the effectiveness of vaccination has led to the re-emergence of anti-vaccine ways of thinking.

This is mainly due to the wrong perception of vaccination, which includes the lack of public knowledge about

it.13 A high percentage of respondents have given their definition of vaccines, but also a high number of them

could not name either one vaccine-preventable disease. A very small number recognized the concept of

“collective immunity”, although some have commented on how the welfare of the community depends on the

decisions of individuals. Considering the educational background of the study group, we consider that the

number of respondents of 11% who did not know what vaccines are, is not worrying and is with correlation

with other studies.14

The media often refer to parents of non-vaccinated children as “anti-vaxxers” – a pejorative notion that implies

that those parents are against all scientific thoughts behind the process. In public health, it is more appropriate

to use the term “vaccination sceptics”, which developed into a concept that includes any parents with a

suspicion of the need for childhood vaccinations, in order to improve the immunity and protect the child itself.15

It is estimated that 75-80% of users search for health information on internet portals instead of receiving them

from a medical professional or from the accredited scientific literature.6 Even the advice of a healthcare

professional becomes only one more opinion on the Internet.16 Given that we are witnessing an increasing

number of sensationalistic headlines, it is reasonable to ask how much has this topic fallen under that

influence as well, and lost the thread of investigative journalism that must be present in all news segments,

especially those associated with professional medical themes such as childhood vaccination.

Setting vaccinations as a legal obligation can be considered a strategy for increasing the number of

vaccinated children within a regular immunization program, but with that, we have to bear in mind the delicate

balance between personal freedom and binding public health policies.17, 18 A similar problem was found in a

study conducted in Switzerland,19 where several parents claimed the belief that non-coercion to take MMR

vaccines in Switzerland was because it is very unlikely for their child to suffer from smallpox. In the reports of

the vaccine sceptic parents dominates the view that the MMR vaccine would be mandatory, and not just

advised from health authorities, if it were a serious virus and a deadly disease. It is often disregarded that

each parent wants the best possible option for their child, based on the information that they possess

Fears in terms of vaccine safety, lack of trust in the health care system and dissatisfaction with the quality of

the vaccine dialogue, are all factors which are associated with parental indecision about vaccination and the

continues growth of the vaccine skeptics.6

The aggravating circumstance is also the fact that 10% of health workers with whom the parents came in

contact with, advised against the immunization of their child. This dissonance in the scientific circles itself

deepens the parent’s skepticism towards the immunization process. A Canadian study found that the trust in

professional staff has significantly decreased, to the extent that calling for expert opinion and evidence is often

considered manipulative.20 Nonetheless, making decisions without references, often makes information

incomplete and more susceptible to different interpretations. Taking this point into account, referring to

scientific and medical references is not so convincing today, as it used to be. This entire process cannot be

left up to the parents themselves, and the role of a healthcare professional, in this case, is based on them

being a referent person who can provide basic knowledge and guide the parents throughout the decision-

making process. Healthcare workers are advised to have access to verified information in order to counteract

inaccurate statements related to the risks associated with vaccination and those statements associated with

the diseases which vaccines prevent, while highlighting the shortcomings of missed or late immunization.

However, attention should be paid to communication style and the approach towards parents when discussing

these thematical units. 9

Political representatives of the health sector and representatives of public health institutions are invited to

publicly explain the thought process behind the idea of non-compulsory vaccination.21, 22 This can be done by

emphasizing the democratic and ethical character of the Tuzla Canton health policies, as well as the need for

positive engagement of parents by giving them some responsibility when it comes to the health of their

children.

The aim of this study was to qualitatively and quantitatively investigate the literacy, attitude and knowledge of

parents about vaccines and the decision-making process on vaccination in the Tuzla Canton, i.e. Bosnia and

Herzegovina. Although interactive web technologies represent a potential solutional approach towards dealing

with this topic in the near future, based on the results of this study, we strongly advise direct engagement of

parents with carefully presented information based on evidence. It became clear that we need better and

more efficient ways of informing and engaging parents who are skeptical about vaccines. It should be

emphasized that the non-compulsory vaccination policy cannot be justified by the existence of a reduced risk

of smallpox or high risk of adverse effects of the MRR vaccines, but quite the contrary: this non-compulsion

exists to increase the responsibility of the parents and further empower the parental role itself.

Efforts should be made to ensure that parents receive verified information on vaccination and, more

importantly, skills to find, evaluate and understand other information regarding this topic. In turn, this

increases the perception of parents about their own competence and thus contributes to their capacity to

make the final decision for themselves. Based on all of the above, we can conclude that the fight against

disinformation related to vaccines and related areas, is necessary through learning and constant education,

but often, that alone is not sufficient.

To our knowledge, this is the first study which examines with literacy, attitudes and knowledge behind the

decision-making process when it comes to the topic of vaccination in the Tuzla Canton. This paper presents

one of the starting points for further development of policies, strategies and other studies on this topic in Tuzla

Canton, as well as throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina.

We would like to thank University of Tuzla and Public Health Institute of Tuzla Canton for allowing us the use of

their facilities for printing purposes while packing and distributing questioners need to conduct this research.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors whose names are listed on this paper certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in

any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in

speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and

expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional

relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

1. Arnup K. “Victims of vaccination?”: opposition to compulsory immunization in Ontario, 1900-90. Can Bull Med Hist. 1992; 9(2): 159-76.

2. Wolfe RM, Sharp LK. Anti-vaccinationists past and present. BMJ. 2002; 325(7361): 430-2.

3. Colgrove J. “Science in a democracy”: the contested status of vaccination in the Progressive Era and the 1920s. Isis. 2005; 96(2): 167-91.

4. Baxter R, Ray P, Tran TN, Black S, Shinefield HR, Coplan PM, et al. Long-term effectiveness of varicella vaccine: a 14-Year, prospective cohort study. Pediatrics. 2013; 131(5): e1389-96.

5. Bennett P, Smith C. Parents attitudinal and social influences on childhood vaccination. Health Educ Res. 1992; 7(3): 341-8.

6. Brown KF, Shanley R, Cowley NA, van Wijgerden J, Toff P, Falconer M, et al. Attitudinal and

demographic predictors of measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine acceptance: development and validation of an evidence-based measurement instrument. Vaccine. 2011; 29(8): 1700-9.

7. Roberts RJ, Sandifer QD, Evans MR, Nolan-Farrell MZ, Davis PM. Reasons for non-uptake of measles, mumps, and rubella catch up immunisation in a measles epidemic and side effects of the vaccine. BMJ. 1995; 310(6995): 1629-32.

8. Dube E, Gagnon D, Nickels E, Jeram S, Schuster M. Mapping vaccine hesitancy–country-specific characteristics of a global phenomenon. Vaccine. 2014; 32(49): 6649-54.

9. Opel DJ, Heritage J, Taylor JA, Mangione-Smith R, Salas HS, Devere V, et al. The architecture of provider-parent vaccine discussions at health supervision visits. Pediatrics. 2013; 132(6): 1037-46.

10. Smailbegovic MS, Laing GJ, Bedford H. Why do parents decide against immunization? The effect of health beliefs and health professionals. Child Care Health Dev. 2003; 29(4): 303-11.

11. Asch DA, Baron J, Hershey JC, Kunreuther H, Meszaros J, Ritov I, et al. Omission bias and pertussis vaccination. Med Decis Making. 1994; 14(2): 118-23.

12. Larson HJ, Smith DM, Paterson P, Cumming M, Eckersberger E, Freifeld CC, et al. Measuring vaccine confidence: analysis of data obtained by a media surveillance system used to analyse public concerns about vaccines. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013; 13(7): 606-13.

13. Haverkate M, D’Ancona F, Giambi C, Johansen K, Lopalco PL, Cozza V, et al. Mandatory and

recommended vaccination in the EU, Iceland and Norway: results of the VENICE 2010 survey on the ways of implementing national vaccination programmes. Euro Surveill. 2012; 17(22).

14. Jarrett C, Wilson R, O’Leary M, Eckersberger E, Larson HJ, Hesitancy SWGoV. Strategies for

addressing vaccine hesitancy – A systematic review. Vaccine. 2015; 33(34): 4180-90.

15. Glanz JM, Kraus CR, Daley MF. Addressing Parental Vaccine Concerns: Engagement, Balance, and Timing. PLoS Biol. 2015; 13(8): e1002227.

16. Gross L. A broken trust: lessons from the vaccine–autism wars. PLoS Biol. 2009; 7(5): e1000114.

17. Larson H, Leask J, Aggett S, Sevdalis N, Thomson A. A Multidisciplinary Research Agenda for

Understanding Vaccine-Related Decisions. Vaccines (Basel). 2013; 1(3): 293-304.

18. Streefland P, Chowdhury AM, Ramos-Jimenez P. Patterns of vaccination acceptance. Soc Sci Med. 1999; 49(12): 1705-16.

19. Fadda M, Depping MK, Schulz PJ. Addressing issues of vaccination literacy and psychological

empowerment in the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccination decision-making: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2015; 15: 836.

20. Kata A. A postmodern Pandora’s box: anti-vaccination misinformation on the Internet. Vaccine. 2010; 28(7): 1709-16.

21. Omer SB, Peterson D, Curran EA, Hinman A, Orenstein WA. Legislative challenges to school

immunization mandates, 2009-2012. JAMA. 2014; 311(6): 620-1.

22. Orenstein WA. The role of measles elimination in development of a national immunization program. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006; 25(12): 1093-101.

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()