Rahman N. An economic analysis of refugee health policy and a structural comparison of the Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative with Colorado, Kentucky, and Minnesota. HPHR. 2021;30.

DOI:10.54111/0001/DD5

This paper aims to discuss refugee admission from a public health perspective; appraise refugee policy changes by the United States as compared with the approaches taken by Canada; evaluate the impact of refugees on the American and Canadian economies; and assess the structure of the Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative compared with similar programs in Colorado, Kentucky, and Minnesota. This project utilizes an extensive literature review incorporating data from various governmental, academic, and journalistic resources to verify its perspectives. Screening protocols for refugees are explored to demonstrate the low risk of communicable diseases from this population. The United States and Canada are juxtaposed in regard to actual and theorized quotas for refugee admission and budgetary resource allocation towards refugee services. The impact of refugees on the Canadian and American economies through entrepreneurship and tax contributions is considered. The Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative (PRHC), an organizational method that synchronizes refugee care amongst three resettlement agencies and eight academic medical centers, is compared with similar frameworks in Colorado, Kentucky, and Minnesota. This article asserts that the United States would benefit if governmental agencies studied policies adopted by Canada and shifted refugee regulations accordingly. The Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative is presented as a framework for refugee care coordination that could serve as a model for other American environments to emulate. Partnerships with local academic health centers and resettlement agencies, a centralized refugee health database, longitudinal healthcare surveys, and quarterly meetings with stakeholders are propounded as methods to improve refugee care in America.

“Give me your tired, your poor/Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free/The wretched refuse of your teeming shore” (Mettler, 2017). Those words, penned by Emma Lazarus and proudly engraved in bronze on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty, proclaim a lofty aspiration for the United States: that this nation, above all others, will embrace the exiled and provide a safe haven for the persecuted. Refugees forced to flee their country to escape war, persecution, or natural disasters exemplify a group of people that the US, at least according to this proclamation, should welcome with open arms. Unfortunately, America has often fallen short of this ambition, particularly in recent history. In a Pew Research Center Poll conducted in 2018, only 51% of Americans felt that the US had a responsibility to accept refugees, a drop from 56% in 2017 (Hartig, 2018).

Infamously, refugee policy in the United States was dramatically shifted on January 27, 2017. President Trump issued an executive order that banned travel to the USA from “seven predominantly Muslim countries (Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen) for 90 days, suspended the US resettlement program for all refugees for 120 days, indefinitely suspended the entry of Syrian refugees, and reduced the number of resettled refugees from 110,000 to 50,000” (Spiegel & Rubenstein, 2017). This order created chaos and confusion around the world, negatively impacting travelers, healthcare workers, and humanitarian efforts. The Trump administration has continued to restrict refugee entrance into the United States and sought various methods to undermine financial and political support of the refugee population (Spiegel & Rubenstein, 2017). In this political climate, healthcare providers must band together to ensure that refugees are not underserved or excluded and remain healthy, vital contributors to society.

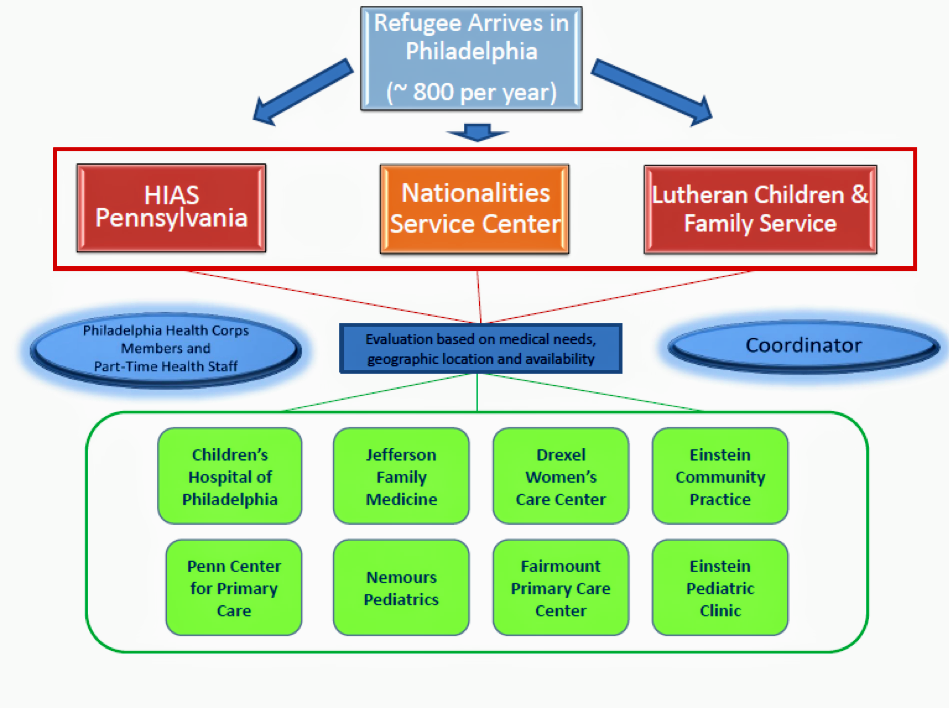

Inter-organizational collaborations are essential to optimize refugee healthcare and support the integration of these newcomers into their community and society at large. The Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative (PRHC) is a patient-centered healthcare delivery model that highlights the importance of partnerships between multiple institutions in order to provide the best care. This program began as a pilot at the Nationalities Service Center and Thomas Jefferson University’s Department of Family and Community Medicine in 2007. Before the foundation of this enterprise, refugees were charged with locating health centers on their own prerogative, which often led to delays and lack of specialty care. Since the establishment of the PRHC, this alliance has expanded to encompass three resettlement agencies and eight health clinics throughout the nearby region, optimizing communication and healthcare delivery for this population (Altshuler, 2017). This model may provide a potential solution for other cities to emulate in their approach to refugee healthcare.

This paper discusses healthcare screening protocols to dispel misconceptions about the risk of communicable diseases from the refugee population. America and Canada are examined for differences in governmental regulation and the economic impact of refugees. The structure of the Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative is compared with similar programs in Colorado, Kentucky, and Minnesota.

This project utilizes an extensive literature review incorporating data from various governmental, academic, and journalistic resources to verify its perspectives. This information was obtained from the Centers for Disease Control, the Federal Register, the Washington Post, the Lancet, the American Journal of Public Health, Harvard Public Health Review, and the Annals of Epidemiology, amongst other reputable sources. Search engines included Google Scholar with input phrases such as “Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative,” “refugee impact on economy,” “Canada refugee policy,” “US refugee budget,” and other related terms. Additional resources were obtained at Thomas Jefferson University. Dr. James Plumb and Dr. Rickie Brawer, co-directors of the Center for Urban Health at Thomas Jefferson University, facilitated the acquisition of Philadelphia refugee data and relevant articles. Ariel MacNeill, Senior Manager of Health Access and Specialized Supports at the Nationalities Services Center, and Dr. Kevin Altshuler, Director of the Jefferson Center for Refugee Health, were interviewed to further comprehend the structure and function of the Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative.

Policies in Canada and the United States are evaluated based on their current framework, future plans, initial cost, and long-term economic impact. Refugee admission rates and fiscal year thresholds in the United States and Canada under current governmental regimes are compared. The original expense to process refugees is contrasted against the long-term benefit that this populace and their progeny provide to the economy. The structure of the Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative is examined for its impact on refugee care through preventative screenings and specialty testing. The possible utility of this framework for refugee healthcare delivery in other American environments is assessed through comparison with programs in Colorado, Minnesota, and Kentucky. These particular programs were selected for assessment because of their structural similarity with the Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative (DiVito, Payton, Shanfeld, Altshuler, & Scott, 2016).

A common misconception is that refugees pose a public health risk because they may carry disease into the community. In fact, the United States employs one of the most stringent refugee screening processes in the world. Refugees undergo extreme scrutiny, including medical screening and security checks, to prevent this issue from occurring via a process that can take 18 to 24 months (Spiegel & Rubenstein, 2017). The Immigration and Nationality Act and Public Health Service Act mandate that all immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers must undergo medical screening before entering the United States (Aliens with Diseases of Public Health Significance, 2012). These screenings can be conducted by “panel physicians” outside the United States or “civil surgeons” within the country (Russell, Pogemiller, & Barnett, 2017). People may be rejected from entry because they do not have proof of vaccination against preventable diseases such as mumps, measles, rubella, polio, tetanus and diphtheria toxoids, pertussis, influenza type B and hepatitis B (Criteria for Vaccination Requirements for U.S. Immigration Purposes, 2009). Physical or mental health disorders that pose a risk to the welfare of others may also be grounds to reject applicants (Detention of aliens for physical and mental examination, 2012). In 2010, HIV was removed from the list of inadmissible health conditions (Removal of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) from Definition of Communicable Disease of Public Health Significance, 2009). HIV screening is still recommended for newcomers. More recently, revisions to the medical screening process were adopted which removed chancroid, granuloma inguinale, and lymphogranuloma venereum as inadmissible health-related conditions; revised the definitions and evaluation criteria for mental disorders, drug addiction and abuse; and clarified the evaluation requirements for tuberculosis (Medical Examination of Aliens—Revisions to Medical Screening Process, 2016). Crucially, mental health screening is conducted for all (Russell, Pogemiller, & Barnett, 2017). With all of these regulations in place, refugees are often less dangerous to American citizens than current residents from a communicable disease perspective.

Hostility towards refugees in public speeches by the President and high-ranking officials in his administration has translated into concrete governmental actions against this vulnerable population in the United States. A prime example occurred when President Trump suspended the refugee resettlement program for all refugees for 120 days, indefinitely suspended entry for Syrian refugees, and reduced the refugee target quota from 110,000 to 50,000 (Spiegel & Rubenstein, 2017). Focused on diminishing refugee numbers and reducing costs, America has failed to recognize the long-term economic and societal benefits that refugees can provide to the public. Canada, however, has wholeheartedly embraced this potential advantage.

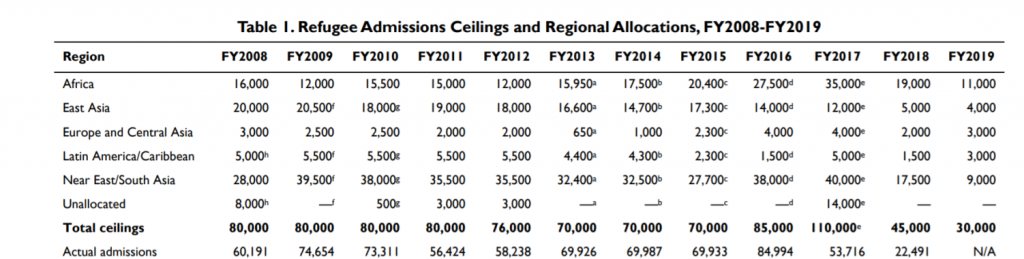

An examination of refugee admission numbers over the past decade in the United States plainly demonstrates this divergence in opinion. As depicted in Table 1, the number of admitted refugees closely aligned with the admission ceiling from 2013 and 2016 as the United States accepted between 70,000 and 85,000 refugees (Bruno, 2018). Those thresholds were set by the Obama administration and were largely upheld.

Table 1 — US Refugee Admission Ceilings & Regional Allocations, 2008-2019

Source: Bruno, A. (2018). Refugee Admissions and Resettlement Policy (CRS Report No. RL31269). Retrieved from Congressional Research Service website: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL31269.pdf

However, the number of refugees admitted into the United States changed in 2017 and 2018. The many efforts by the Trump administration to discourage refugees from entering the United States, including a reduction in the admission ceiling from 110,000 in 2017 to 45,000 in 2018, culminated in a dramatic drop-off in the number of refugee admissions. Only 22,491 refugees were admitted in 2018, contrasting sharply with the 84,994 refugees admitted in 2016 (Bruno, 2018). An admission threshold of just 30,000 refugees has been ratified for the fiscal year 2019, a 73% reduction from the 2017 goal of 110,000 (Bruno, 2018). This abrupt decrease in admittance threshold in just two years highlights the restrictive stance of the Trump administration towards refugee policy.

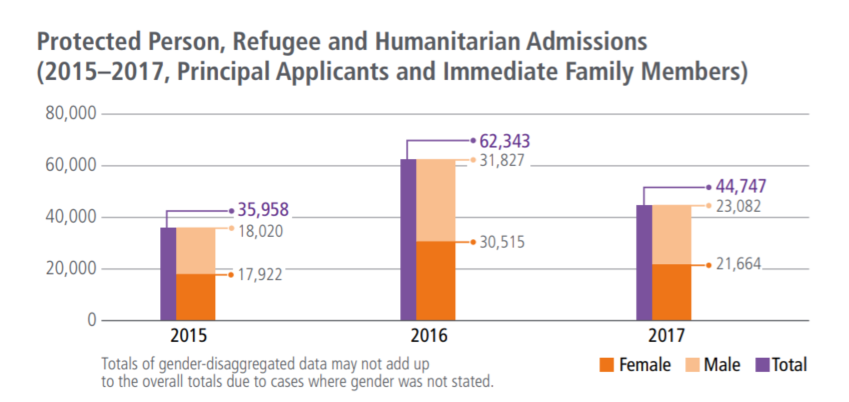

Table 2 — Canada Protected Person, Refugee, and Humanitarian Admissions, 2015-2017

Source: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (2018a). 2018 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration.Ottawa: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/rcc/migration/ircc/english/pdf/pub/annual-report-2018.pdf

In contrast, Canada continued to admit a large number of protected persons and refugees from 2015 to 2017, particularly in relation to its overall population. Canada has a population of only 37 million whereas the United States has a population of nearly 330 million, yet Canada accepted a similar number of refugees over this time span (Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, 2018a). Canada has embraced refugees from war-stricken nations, inviting 25,000 Syrian refugees to the country by February 27th, 2016 (Amri, 2016). These numbers have only continued to increase since that time, and the government has already pledged a further uptick in refugee admissions in the near future (Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, 2018a).

Table 3 — Canada 2019-2021 Immigration Levels Plan

Projected Admissions – Ranges | Low 2019 | High 2019 | Low 2020 | High 2020 | Low 2021 | High 2021 |

Refugees, Protected Persons, Humanitarian, and Other | 43,000 | 58,500 | 47,000 | 61,500 | 48,500 | 64,500 |

Source: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (2018a). 2018 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration.Ottawa: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/migration/ircc/english/pdf/pub/annual-report-2018.pdf

As shown in Table 3, Canada has announced a target refugee admission goal high of 64,500 and a low of 48,500 in 2021, an increase from their admission rate of 44,747 refugees in 2017 (Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, 2018a). The overall trajectory for Canadian refugee admissions is clearly in the opposite direction of the United States.

As depicted in Tables 4 and 5, the United States and Canada devote similar monetary funding towards refugees. In 2017, the United States spent a total of 2.14 billion dollars to fund services for refugee resettlement assistance (Bruno, 2018). In the same year, Canada was forecasted to spend $1.74 billion specifically for immigrant and refugee selection and integration, with an additional $226 million spent on internal services that supported the overall immigration effort (Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, 2018b).

Table 4 — US Refugee Resettlement Assistance Funding, 2015-2017 (in millions of dollars)

Programs | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

Social Services | 149.9 | 170.0 | 155.0 | Refugee Support Services*: 202.4 |

Targeted Assistance | 47.6 | 52.6 | 47.6 | |

Preventative Health | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.6 | |

Subtotal | 202.1 | 227.2 | 207.2 | |

Transitional/Cash and Medical Services | 383.3 | 532.0 | 490.0 | 244.9 |

Victims of Trafficking | 15.8 | 18.8 | 18.8 | 23.8 |

Victims of Torture | 10.7 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 10.7 |

Unaccompanied Alien Children | 948.0 | 892.4 | 1414.6 | 1569.6 |

Total | $1559.9 | $1681.1 | $2141.3 | $2051.4 |

Source: Bruno, A. (2018). Refugee Admissions and Resettlement Policy (CRS Report No. RL31269). Retrieved from Congressional Research Service website: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL31269.pdf

* “Beginning in FY2018, the Refugee Support Services category consolidates funding for Social Services, Targeted Assistance, and Preventive Health” (Bruno, 2018).

Table 5 — Canada Budgetary Planning Summary, 2015-2021 (in millions of dollars)

Core Responsibilities and Internal Services | 2015-2016 Expenditures | 2016-2017 Expenditures | 2017-2018 Forecasted | 2018-2019 Forecasted | 2019-2020 Forecasted | 2020-2021 Forecasted |

Visitors, International Students and Temporary Workers | N/A* | N/A* | 197.6 | 179.9 | 198.5 | 202.3 |

Immigrant and Refugee Selection and Integration | 1744.3 | 1799.1 | 1716.3 | 1761.4 | ||

Citizenship and Passports | -79.9 | 153.9 | 217.3 | 177.4 | ||

Subtotal | 1318.7* | 1379.0* | 1862.0 | 2133.0 | 2132.1 | 2141.1 |

Internal Services | 217.8 | 221.0 | 226.4 | 222.7 | 214.0 | 207.9 |

Total | 1536.5 | 1600.0 | 2088.4 | 2355.7 | 2346.1 | 2349.0 |

Source: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (2018b). Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada Departmental Plan 2018–2019.Ottawa: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/migration/ircc/english/pdf/pub/dp-pm-2018-2019-eng.pdf

* “Due to changes in Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s reporting framework in fiscal year 2018–2019, expenditures by core responsibility for 2015–2016 and 2016–2017 are not available” (Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, 2018b).

At the University of Toronto, the macro-economic Forecasting and User Simulation (FOCUS) model was used to simulate the impact that a hypothetical increase in immigration would have on the Canadian economy. This study demonstrated only positive effects on gross domestic product, gross domestic product per capita, investment, productivity, taxes, and net government balances, with virtually no impact on unemployment (Dungan, Fang, & Gunderson, 2012). This projection supports the overall perspective towards immigration as a probable boon for the economy.

Refugees are no exception to this outlook but do not enjoy the same background as other immigrants. They often arrive stripped of all material possessions due to violent situations. In an effort to provide these newcomers with the support that they need to become vital contributors to society, Canada provides financial assistance to incoming refugees through the Refugee Assistance Program. Between FY 2010-11 and FY 2014-15, the average yearly cost per client for the Refugee Assistance Program was $10,573. This average cost can be broken down into $7,296 for income support paid directly to RAP clients; $2,716 for service provider organizations; and $561 for other miscellaneous costs. Over this same period, the average yearly cost per client actually decreased by $324, or 3% (Evaluation Division, 2016).

Thanks to these specialized efforts by the Canadian government, refugees are thriving and contributing to their communities. According to the 2018 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration, delivered by the Honourable Ahmed Hussen, P.C., M.P., “immigrants of all categories including refugees tend to have positive outcomes across a range of economic indicators” (Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, 2018a). In fact, in the year 2017, economic immigrants who had lived in Canada for at least five years actually “exceeded Canadian average earnings by 6% and were 15-24% more likely to be working than Canadian-born residents” (Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, 2018a). The descendants of these immigrants often attain a higher level of education as well. In 2016, nearly half of all immigrants between 25 and 64 years of age held a bachelor’s degree compared to under a quarter of Canadian-born people in that same age group (Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, 2018a).

Refugees also contribute to the American economy at a rate that outstrips the initial costs to process their admissions. The five year American Community Survey studied the 3.4 million refugees who have arrived since 1975 and demonstrated a strong upward economic trajectory. According to this report, “refugees earn more than $77 billion in household income and paid almost $21 billion in taxes in 2015” (New American Economy, 2017). Refugees also help drive the business industry. 13% of refugees were entrepreneurs in 2015, compared to 11.5% of non-refugee immigrants and just 9.0% of the US-born population (New American Economy, 2017). Of particular note, refugees who have lived in the US for less than five years have a median household income of $22,000, but that figure more than triples over subsequent decades. Refugees who have lived in the US for over 25 years had a household income of $67,000 in 2015, whereas the US median household income overall in the same year was $53,889 (New American Economy, 2017).

Refugees must obtain support when they first arrive in the United States and in later months, particularly for healthcare requirements. The Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative, a partnership between non-governmental agencies, connects refugees with resettlement agencies and health centers to receive primary screenings and specialty care. The Nationalities Service Center, Lutheran Children and Family Service Southeastern Pennsylvania, and the HIAS Pennsylvania resettle refugees entering the Philadelphia region. These agencies ensure that this population acquires housing, education, health insurance, community orientation, and an initial domestic health screening (DiVito, Payton, Shanfeld, Altshuler, & Scott, 2016).

Figure 1 —Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative, Updated November 2015

Source: DiVitoB, Payton C, Shanfeld G, Altshuler M, Scott K (2016). A Collaborative Approach to Promoting Continuing Care for Refugees: Philadelphia’s Strategies and Lessons Learned. Harvard Public Health Review 9.

Many states, including Pennsylvania, did not possess statewide screening systems for this purpose, which led to serious disruption in continuity of care for the incoming refugee population, especially when transitioning to a different medical provider. Thankfully, through this collaborative, refugees are placed in touch with the Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania, Jefferson Department of Family Medicine, Drexel’s Women’s Care Center, Einstein Community Practice, Penn Center for Primary Care, Nemours Pediatrics, Fairmount Primary Care Center, or Einstein Pediatric Clinic by their resettlement agency, according to their individual needs. Previously, refugees needed to independently obtain referrals to visit community health centers. With the creation of the PRHC, refugees receive assistance from health coordinators and clinic liaisons to identify the most appropriate center for their discrete medical concerns. Also, all eight health centers accept regular referrals from the three Philadelphia resettlement agencies. This open clinic network allows medical providers to match service demand with capacity (DiVito, Payton, Shanfeld, Altshuler, & Scott, 2016). These organizations represent the vast majority of academic health centers in the region with a corresponding armament of resources at their disposal. This combination of medical talent ensures that refugees are provided with the best quality of care while presenting unique educational opportunities for healthcare personnel (DiVito, Payton, Shanfeld, Altshuler, & Scott, 2016).

The PRHC has positively impacted refugee healthcare in the region. Newly arrived refugees to Philadelphia are seen on average in 29 days for their initial screening appointment, a reduction from 80 to 90 days before the inception of this collaborative (DiVito, Payton, Shanfeld, Altshuler, & Scott, 2016). Coordination between the PRHC and the City Benefits Office has led to enrollment in health insurance within 5 days of arrival. Before the PRHC, no specialist or preventative screenings were scheduled for refugees except in the case of an extremely serious or life-threatening condition. Now, at a single PRHC provider site, “more than 7,980 primary care and 2,790 specialist appointments have been completed” (DiVito, Payton, Shanfeld, Altshuler, & Scott, 2016). A goal of the PRHC is to establish a citywide database that tracks refugee health outcomes and communicates these results to the state refugee health program (DiVito, Payton, Shanfeld, Altshuler, & Scott, 2016). The PRHC coordinators, support staff at all of the refugee clinic sites and refugee resettlement agencies, and representatives of the city government meet quarterly to discuss improvements to the current system. Inter-agency networking fostered by the PRHC has led to sharing of best practices, collaborative data collection, research collaborations, and improved access to specialty care for the refugee population in Philadelphia (DiVito, Payton, Shanfeld, Altshuler, & Scott, 2016).

Comparable programs exist in other states such as Colorado, Kentucky, and Minnesota. However, there are structural changes that create differences in refugee care. There are 13 Wilson-Fish states, with Colorado and Kentucky among them. Wilson-Fish programs, federally-funded alternatives to traditional state-run refugee programs, provide support to refugees with cash, medical services, employment assistance, English language training, and other social services to encourage early employment and economic self-sufficiency. They are administered by either states in coordination with local non-governmental agencies; private non-profit agencies with state assistance; or private non-profit agencies without state assistance (Wilson-Fish Alternative Program Guidelines, 2017).

Colorado has a state-run Refugee Services Program that does not offer any direct services, but is responsible for the coordination of refugee resettlement with local non-governmental partners. Similar to the Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative, this program utilizes three designated refugee resettlement agencies that provide access to job training, educational services, and cash assistance (Taintor & Lichtenstein, 2016). However, the Colorado system does not have the same level of communication and collaboration amongst academic health centers in the region, which limits the integration of resources towards refugee care. The five-year longitudinal Refugee Integration Survey and Evaluation (RISE) study investigated refugee integration in Colorado through ten variables: employment and economic sufficiency; education and training; children’s education; health & physical well-being; housing; social bonding; social bridging; language & culture; safety & stability; and civic engagement. Health & Physical Well‐Being was the only category that showed a dramatic reduction in overall scores over five years. This negative trend likely occurred because the younger generation was not adequately transitioned to long-term health care after their initial screenings (Taintor & Lichtenstein, 2016).

In the case of Kentucky, another Wilson-Fish state, the refugee assistance program is operated by a nonprofit organization rather than the state government. Kentucky employs the Reception and Placement Program to address refugee needs upon initial entrance to the country. The Kentucky Office for Refugees, located within Catholic Charities of Louisville, is the administrative coordinator for post-arrival services (“Refugee Resettlement in Kentucky”). The Office of Refugee Resettlement conducts quarterly meetings with partners such as public health departments, medical and mental health providers, police departments, and government officials to address refugee employment, housing availability, and health care access. This information is collated and forwarded to the Department of State in order to assist with decision-making in subsequent governmental legislation and budgeting (Kentucky Office for Refugees, 2019).

The Minnesota Department of Health uses the Refugee and International Health Program to contract with resettlement agencies in a comparable manner to Philadelphia, Colorado, and Kentucky. This allows incoming refugees to receive appropriate healthcare screenings upon arrival. However, Minnesota lacks the significant affiliations between academic institutions found in Philadelphia. An additional feature in the Minnesota Refugee Health Program is a centralized refugee screening and data management tool. Public health locations and screening clinics report all screening results to the state, producing a database that can provide valuable insight into the effectiveness of current programming and help target initiatives for the future (Minnesota Department of Health, 2019).

As illustrated in Table 6, all of these programs employ various strategies to administer refugee care. Emulation of the unique partnership between academic health centers offered by the Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative would likely improve other refugee programs in America. Partnerships with local resettlement agencies and medical institutions, a centralized refugee data management tool, longitudinal healthcare surveys, and quarterly meetings with stakeholders may all contribute to the improvement of refugee care in America (de Bocanegra, 2018).

Table 6 —PRHC Compared with Similar Programs in Colorado, Minnesota, and Kentucky

| Program | State Run? | Partnered with Resettlement Agencies? | Coordination Between Medical Centers? | Longitudinal Healthcare Survey? | Centralized Refugee Database? | Quarterly stakeholder meeting? |

| Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative | X | X | X | |||

| Colorado Refugee Services Program | X | X | X | |||

| Kentucky Office for Refugees | X | X | ||||

| Minnesota Refugee and International Health Program | X | X | X |

The incredible complexity and pace of change with refugee policy at the federal, state, and local stage creates a significant challenge to surmount when collecting and presenting information. Concrete data about the refugee population is often restricted due to limited resources for studies and difficulty with long-term follow-up and assessment of outcomes. This paucity of available data prevented a more in-depth analysis of structural differences between states regarding refugee healthcare policy, coordination, and integration. The perspective advocated by this article cannot fully encompass all possible approaches towards this controversial topic, but it is the intention of the author to explore and elucidate feasible strategies that will optimize refugee care at the local and national levels and ultimately maximize the integration and contribution of this population into society.

There are many lessons that the United States may derive from an examination of the Canadian approach towards refugee policy. While America has decided to cut refugee admission numbers dramatically under the Trump Administration (Bruno, 2018), Canada has pledged to increase admission numbers over the next few years (Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, 2018a). Canada and the US both allocate approximately $2 billion a year towards refugee processing and services. In exchange for that initial investment, refugees provide a significant boon to both societies with entrepreneurship and tax contributions. Once they become interwoven into the fabric of their respective societies, these refugees and their descendants help drive economic growth (New American Economy, 2017). The incorporation of even more refugees with adequate financial support upon initial entrance will provide more economic benefits to American industry and society.

The Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative provides a framework to synchronize resettlement agencies and academic health centers in order to effectively deliver healthcare services to refugees (DiVito, Payton, Shanfeld, Altshuler, & Scott, 2016). Other refugee programs throughout the United States may benefit by replicating features of this collaborative network. Systems in Colorado, Minnesota, and Kentucky demonstrate that a centralized refugee database, longitudinal healthcare surveys, and quarterly meetings with stakeholders may serve as supplemental mechanisms to further promote refugee access and care.

Dr. Naveed A. Rahman, MD is a general surgeon in Syracuse, New York. He is with the State University of New York (SUNY), Upstate Medical University, Department of Surgery.

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()