The Interdisciplinarian

By Sofia Weiss Goitiandia

As seen through Dalia's eyes:

Reflections on the world of Global Health from a pioneering Sudanese activist - Part 1

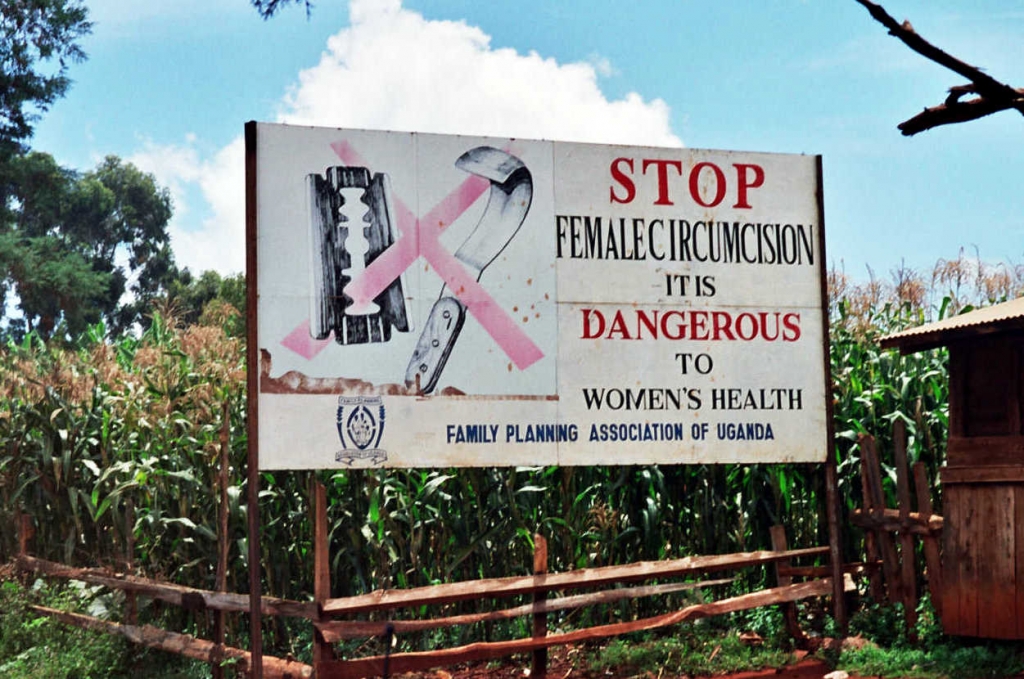

For this set of articles, I interviewed Dalia Elhag, a medical doctor from Sudan, and graduate of the master’s programme in Global Health at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden – where I was also a student this academic year. Dalia also has a long history as an activist in the field of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), particularly in advocating against female genital mutilation (FGM), gender-based violence, and child marriage – which are all prevalent in Sudan. Dalia considers herself strongly a feminist, and feels that this is a solid basis – and inspiration – for much of her work.

The articles that follow are a written transcript of our conversations, focusing particularly on her thoughts on the kinds of contributions that can be made towards improving health equity outside of the clinic; reflections on lessons learned and challenges experienced from her (continuing) time as a young activist; as well as her perspective on what ‘decolonising’ global health means in practice.

Part 1

In this article, Dalia introduces herself and how she entered the world of global public health. She tells stories from her childhood and of living across different contexts, which link into a personal conversation about feminism, and the central role it has played in Dalia’s life.

Sofia’s question:

Hi Dalia, it is wonderful to be able to speak with you today. We’re going to start at the very beginning of your career, if that’s OK, so my first question is: what made you go into the medicine and public health spheres? How did you get to the interests that you have now?

Dalia’s answer:

Going into medicine was not really based on interest, but more that it was socially seen as a good thing, the fact that one would study medicine. But then, as I progressed through the years and I was exposed to medical missions, – where you could go to offer medical education sessions and provide care in rural areas – I started to think beyond being a clinical doctor. That was really when I started to realise that health inequities exist, and that you really need not just doctors, but also a strong health system with resources, adequate policies, etc., to make sure that healthcare works. Otherwise, people suffer. Especially people who lack access – the vulnerable populations. And I would see most of the time that these vulnerable populations were women and children, who could not travel so far to access healthcare. So that was the first time that I realised that I wanted to get into global public health, and effect change from ‘higher up’. That was when I started to see the bigger picture.

Sofia:

The bigger picture of the reasons why people were sick, or could get sick?

Dalia:

I guess the bigger picture that you could be a doctor, but that does not necessarily mean that you will be able to treat the patients, because they do not have access to you. So basically, health inequity was the reality that I was not completely aware of initially. Because I lived in the capital city, Khartoum, and whilst you do see that there are people who cannot access healthcare there, it’s far more prevalent in rural areas, where people have to travel – literally travel – just to be able to reach a primary healthcare centre, or to get their children vaccinated. Just the very simple things. And it was very shocking to me, and it opened my eyes.

Sofia:

And so that brought you to global health. But I’m still curious, SRHR – where does that fit in?

Dalia:

So, Sudan is a part of the International Federation of Medical Students Associations, through a student organisation called MedSIN-Sudan (IFMSA, 2021). My university had a lot of members, so my other classmates and people from other batches were really active [in IFMSA], and it got me curious to get involved. And there were different offices that I could join, and it was actually completely by coincidence that my friend was in the SCORA office, which is the Standing Committee on Reproductive Health and Rights including HIV and AIDS (SCORA, 2021). So, actually, I always knew too that I was a feminist – I just also then realised that I could put it to use, and explore more what the issues were; get in touch with the community; and do some good work in this field. In this way, it started sort of by coincidence, and just took off from there.

Sofia:

You say: “I always knew that I was a feminist.” How did you know?

Dalia:

I guess I knew because of the social norms where I come from, where boys and men in general are held in higher regard, and girls as well as women are treated like second-class citizens, or their gender roles are limited. Of course, as time progresses it becomes less pronounced, but in my country, or at least in my community, it still is felt. And I could just see that sometimes my brother, who is younger than me, is allowed to do so things that I am not. For example, he can go out and stay out, whilst I must be back home by six pm. My question was: but why? In my mind, we’re the same. And I literally thought this when I was twelve years old. I was thinking: ‘what is the difference?’ And also, that we should all be equal. I guess from there, I knew that I was a feminist inside. Later, I was exposed to the terminology – the word, feminist – and I remember thinking ‘well, yes, that is exactly what I believe. We should be equal.’ Socially, economically, and politically. Of course, at twelve I did not understand all of it as I do now, the different aspects of it, but I always thought that it should be equal. And I come from a household where my mother and father were both working; they were both contributing; and they were both independent. So, this inspired me. I aspired to be just like my mother. That was also a really big factor for me, in helping me to develop into the person that I am today. I want to be independent. I want to work. And I want to be responsible for myself. I want my freedom – my complete freedom of choice. My experiences, what I’ve seen and what I’ve been exposed to since I was a little child, it has all propelled me towards readily accepting feminism.

Sofia:

You grew up between Sudan and Saudi Arabia, and now you are living in Sweden. What has your experience been of living between these different settings, including from your feminist perspective?

Dalia:

I guess coming to Sweden has been really fulfilling to me, as a woman. This is because I, obviously, coming newly to a country kind of looked up: what are the policies and laws for women? What are my rights here? I was very interested, and I looked up everything from maternity leave to the wage gap to the gender equality index in Sweden. And I’m glad to be able to have all of that now, and I feel much more secure, I guess, in my existence – that I’m not a second-class citizen. But I can’t help but wish that this were the situation where I come from, though both of the countries that I came from are making really great strides, and I’m very happy to see that. It must be said that this was not much of my personal experience when I was living there, though I am really happy to see that the progress is being made. But yes, it has been quite different living in these different contexts.

Sofia:

When you say ‘progress’, what do you mean? What’s changing [in the countries that you are from]?

Dalia:

There is a lot changing, and I think it started with feminist movements in these two countries. Basically, people were just fed up. And these movements have led to tangible changes: for example, women can drive in Saudi Arabia (Coker, 2018). Plus, recently in Sudan there have been steps towards stronger laws, for example, against sexual harassment and assault, which have actually led to Sudan approving the ratification of the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (Sudan Tribune, 2021). This happened in April [2021], in fact – with some reservations though (Sudan Tribune, 2021). But still, they had not ratified it before, and now they are going to do so. It makes it clear that these movements are being listened to, and that there are concrete changes happening. And then also, just generally in society, I feel like women are getting to dress more how they would like, and they are outside more, too. I recently went to Saudi Arabia, a few months ago, and women were working jobs that were previously thought to be only for men. For example, as soon as I landed in the airport, there were women working in the passport controls, which I have never seen in my twenty-something-years of going to Saudi Arabia, and entering the airport at least twice per year. I had never seen that.

Sofia:

This is where, honestly, I realise how disconnected I am sometimes from the reality of much of the world. I would not have said passport control was one of these areas where women would be excluded. I just would not have thought about it.

Dalia:

It’s because it has shifts! And your shift could be at night. So, anything where your shift could be at night is something that you would not work in, as a Saudi woman, particularly. Also, it is in a mixed setting. Saudi women used to work jobs in segregated settings only most of the time (Michaelson, 2019). And then, they did not used to work in the malls as well, and other places, but now there are a lot of women (Ng, 2021). It is amazing to see. And every now and then I see a woman driving, and every time I’m shook – in the most positive way!

Sofia:

It’s really heartening to listen to you speak. I can feel it within myself, this feeling of ‘yeah, women driving!’ It’s so motivational. But then, I wouldn’t think about it in my day-to-day in Spain, or in my daily life in Sweden.

Dalia:

Yes, well not in Sudan either. I personally drive in Sudan, many women do. It’s just in that specific context [in Saudi Arabia], where I was raised for a lot of my life. From my experience, it is quite different, when you see a change happening there. I felt surprised, but obviously in a very good way. Every single time I would go to Sudan and come back to Saudi Arabia, I would see some difference, and that is quite amazing.

Look out for Part 2, coming shortly.

References

Coker, M. (2018, June 24). Saudi Women Can Now Drive. Overcoming Beliefs on Gender Will Be Harder. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/24/world/middleeast/saudi-women-drivers.html

IFMSA. (2021). IFMSA Exchange Portal, MedSIN Sudan. https://exchange.ifmsa.org/exchange/explore/nmo/1134

Michaelson. (2019, July 20). An ‘oasis’ for women? Inside Saudi Arabia’s vast new female-only workspaces. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/jul/20/an-oasis-for-women-inside-saudi-arabias-vast-new-female-only-workspaces

Ng, A. (2021, April 29). Saudi Arabia sees a spike in women joining the workforce, Brookings study shows. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/04/29/saudi-arabia-sees-a-spike-in-women-joining-the-workforce-study-says.html

SCORA. (2021). Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights including HIV and AIDS (SCORA). IFMSA. https://ifmsa.org/standing-committees/sexual-reproductive-health-rights-including-hiv-aids/

Sudan Tribune. (2021). Sudan’s cabinet approves CEDAW ratification—Sudan Tribune: Plural news and views on Sudan. https://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article69497

Like what you read?

More from Sofia Weiss Goitiandia here.