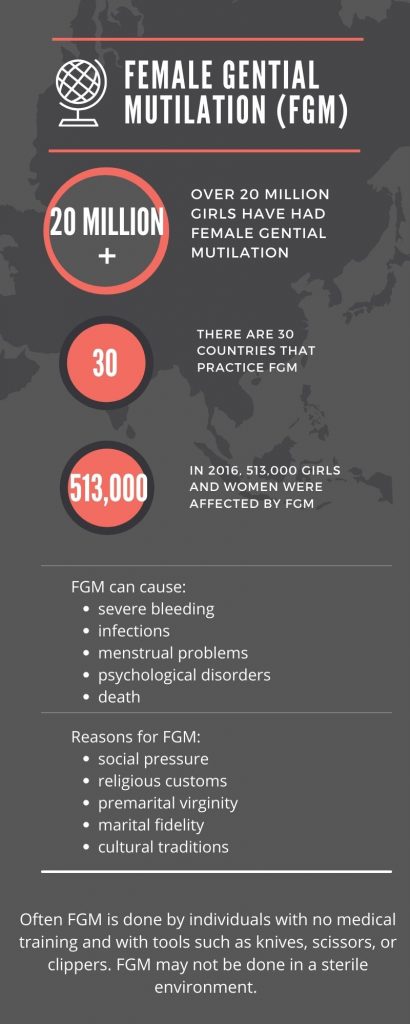

Female genital mutilation (FGM) or female genital cutting (FGC) is the procedure of removing the external female genitalia, or other injury to female genital organs. FGM is done for non-medical reasons and can involve removing partial or total female genitalia.10 More than 20 million girls have had FGM done in 30 countries.10 In 2016, it was estimated that 513,000 girls and women were affected by female genital mutilation.3

FGM has no actual health benefits for girls or women and can cause a variety of health complications. These complications can include: severe bleeding, urinary problems, infections, complications in childbirth, cysts later in life, increased risk of newborn deaths, shock, and death. Long-term complications can include: sexual problems, menstrual problems, childbirth complications, need for later surgeries, and psychological disorders. These psychological disorders span from depression to post-traumatic stress disorder.6,10

Female genital mutilations are performed due to the influence of cultural and societal factors. These factors include: social pressure; fear of being rejected by the community due to social norms; the belief that FGM ensures premarital virginity and marital fidelity; cultural traditions; imitation of neighboring groups; religious customs; and conforming to cultural ideas of femininity and modesty.6,10 Some cultures deem that FGM removes body parts that are viewed as unclean and unfeminine and can enhance men’s sexual pleasure.6.10 Often, those performing FGM have no medical training. Sterile environments are not always possible. The tools that are used are knives, scissors, or clippers. Frequently, steps are not taken to reduce the procedural pain for the girls and women.6

There have been strides in policies to prevent this practice from happening to females in some countries.

There have been several ramifications of FGM due to this practice being viewed internationally as an infringement on human rights principles, norms, and standards. FGM violates the right to freedom from torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment; the principles of equality; right to life; and non-discrimination on the basis of sex; and the right to the highest attainable standard of health.9 In United States, the Strengthening the Opposition to Female Genital Mutilation Act of 2020 was passed, making it illegal to perform FGM.2 Furthermore, FGM is outlawed in 43 countries.8

Female genital cosmetic surgery (FGCS) has arisen in some developed countries. FGCS is identified as procedures that alter the appearance and function of female genitalia.5,8 These elective plastic surgery procedures are characterized as vaginal tightening and vulva remodeling to make the vulva appear more youthful and designed to conform to western beauty standards.4 Procedures also include: reduction in the labia minora and the clitoral hood; plumping of labia majora; liposuction of the mons pubis; and ‘G-spot’ collagen injections.7

There are still potential complications attributed to FGCS, such as infection, adhesions, scarring, dyspareunia, adhesions, and altered genital sensation.1

These Western ideas suggest that women who undergo these genital surgeries will enhance their sexual enjoyment and improve their performance.8

Both female genitalia procedures involve some form of manipulation to the female genitalia and have close similarities as far as influence, culture, and social norms influencing women undergoing these procedures. These procedures stem from cultural ideologies and attitudes that influence and shape social norms of the female anatomy. While FGM is more common among minors and low-income countries and FGCS is more common in industrialized societies, both procedures have the same ideology of reconstructing the female genitalia for sexual enjoyment and improved sexual performance. However, both of these ideals have been disproven. One could argue that beauty standards, purity, sexual performance, and increased sexual enjoyment are not meant for the women who undergo this procedure but are mostly influenced by the desires of their male counterparts.

While both procedures have negative health implications, more research is needed to determine the prevalence and factors of influence for women seeking FGCS. Education on sexual health should be made available to these areas practicing FGM. This would negate the ideology that FGM can enhance men’s sexual enjoyment. Through education, women can have more autonomy about their own bodies and make informed decision about FGM.

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()