Perhaps the most strangely inspiring and damaging years of my life were in secondary school. It was the first time I heard the myth: “Women have 9 parts of lust and 1 part of intellect.” In contrast, surprise, surprise…“Men have 1 part of lust, and 9 parts of intellect.” As a 15-year-old girl, I had been told how impossible it would be for me to do well in the sciences as I blossomed into a young woman due to my own raging hormones. For some reason, my intellect was confined to memorising biological facts but not to doing higher-level cognitive processing that was needed in physics and mathematics. “Physics and mathematics are for boys, and girls do biology” was even parroted by some of my teachers and school friends. Before anyone accuses me of blasphemy – the Office of the Mufti of the Federal Territory of Malaysia had beaten me to it in correcting the myth in a communiqué, which concluded that the statement “Women have 9 parts of lust and 1 part of intellect” has no religious basis in Islam and should not be circulated. Additionally, the Office also stated that in the context of today’s world, women are as competitive as men or even better than men in many areas despite the difficulties and hardships they face (Pejabat Mufti Wilayah Persekutuan, 2019). Regardless of this correction by the Mufti Office, we know that there is no scientific basis for the myth.

My 15-year-old self did not agree with the myth, but since I did not know any better, I struggled trying to comprehend the changes that my body was experiencing, my growing attraction to men, and doing well in school. As a 15-year-old, I did not find the propagation of the myth shocking, though it is shocking to me now to think how normalised misogyny is throughout the lifespan of a woman. Another infamous saying, while I was growing up, had equated women who do not cover their heads and not dressed to the appropriate societal standard to an unwrapped candy, attracting ants. A wrapped candy is a woman who covers herself as per accepted societal standards to save her body for the sole viewing of her future husband. Having said that, I am against the proposed ban on hijab in France (Al Jazeera, 2021). This is a state-sponsored move to control what women wear and is a violation of human rights’ articles 5 (personal liberty) and 9 (freedom of religion and belief). Much of the narrative of being a woman is for the purpose of male validation and acceptance, which is internalised by women at a young age. Whether women cover up or don’t cover up, we cannot seem to satisfy anyone. Why can’t society just let women be?

Policing of the female body did not stop at dress codes. It started with a sense of ownership and guardianship over female bodies and the fear of female sexual enjoyment which are prefaced and veiled in religious vocabulary and rationale. In a 2018 documentary on female circumcision, a Malaysian traditional midwife described the needling of the clitoral hood to satisfy the requirement of a drop of blood, as a way to manage lust, otherwise, these girls will be wild (R.AGE, 2018). According to Rashid & Iguchi (2019), 99.3% of Muslim Malay female infants as young as one month or two months old (median age: 6 years old) experienced type IV FGM/C (female genital mutilation/cutting). They also found that religion is the number one reason for this practice in Malaysia even though FGM/C predates Islam and two northern peninsular Malaysian state muftis stated that FGM/C is not compulsory in Islam and are strongly against the practice (which is incongruent with the 2009 National Fatwa on female circumcision (Ainslie, 2015) – please note that Malaysian fatwas are not legally binding). No long-term medical effects are seen with Type IV FGC compared to the types of FGM/C practiced in Africa, but there are no medical benefits to this practice either. (Rashid & Iguchi, 2019). However, what is worrying is the 20.5% out of 336 medical practitioners who admitted to practicing FGM/C in Malaysia, with a substantial number of doctors practicing Type I FGM/C which involves excision of the visible part of the clitoris (Rashid, Iguchi, & Afiqah, 2020). Although these studies did not find curbing women’s sexuality as a reason for female circumcision, anecdotally, I have found that most Malay Muslim parents believe female circumcision to be necessary for hygiene and to decrease libido. The small cut may heal over time and its effects not visible or impactful to a woman’s physical health (Isa, Shuib, & Othman, 1999; Rashid & Iguchi, 2019), but psychologically, in my opinion, it undermines women because 1) it implies that they cannot control their own sexual urges and have no control their own bodies, therefore extreme measures need to be taken, 2) they have no say over the matter as they were infants when they underwent female circumcision. However, I do not believe individual parents would want to harm their daughters. Parents who advocate for this practice truly believe that this practice is a form of body and spiritual enhancement, therefore it is important to approach this subject sensitively.

While it is convenient to brand FGM/C as a non-Western practice, I argue that female genital cosmetic surgeries (FGCS), which are legal in many Western countries, are also forms of FGM/C. A meta-analysis that explored the contribution of mainstream online content and pornography in a woman’s decision to pursue FGCS found significant interconnected patterns which promoted the normalisation of FGCS: idealised forms of genitalia and pathologisation of genital diversity, the importance of female genital appearance to personal wellbeing and sexual enjoyment, the female body as degenerative and how improvements through surgery can be made (this can be observed in how the vaginoplasty is promoted as vaginal rejuvenation surgery although this is factually incorrect), and that “FGCS is safe, easy and effective” (Mowat, McDonald, Dobson, Fisher, & Kirkman, 2015). Is it informed consent if women are constantly being bombarded with the supposedly ideal, identical images of the vulva anatomy on the Internet that they feel the need to undergo an invasive procedure to “correct” a perfectly normal vulva? Is it not misogynistic to have to surgically change the appearance of your vulva for the masturbation fantasies of men? In a study that looked into the decision-making process of Australian women seeking labiaplasty, online media, peer influence, and negative comments about one’s genital appearance by their partners positively correlated with women wanting to correct their genital appearance (Sharp, Tiggemann, & Mattiske, 2014). These procedures are not without any complications which can be far more physically and emotionally damaging than the Malaysian female circumcision. Many women who had undergone these surgeries have expressed regret due to these complications – which is also another topic to write about by itself.

Arguably, Female Genital Cosmetic Surgery is a form of Female Genital Mutilation. Both are done for non-medical reasons and for satisfying society's sexual politics, in which, patriarchy reigns supreme.

Dr. Hannah Nazri Tweet

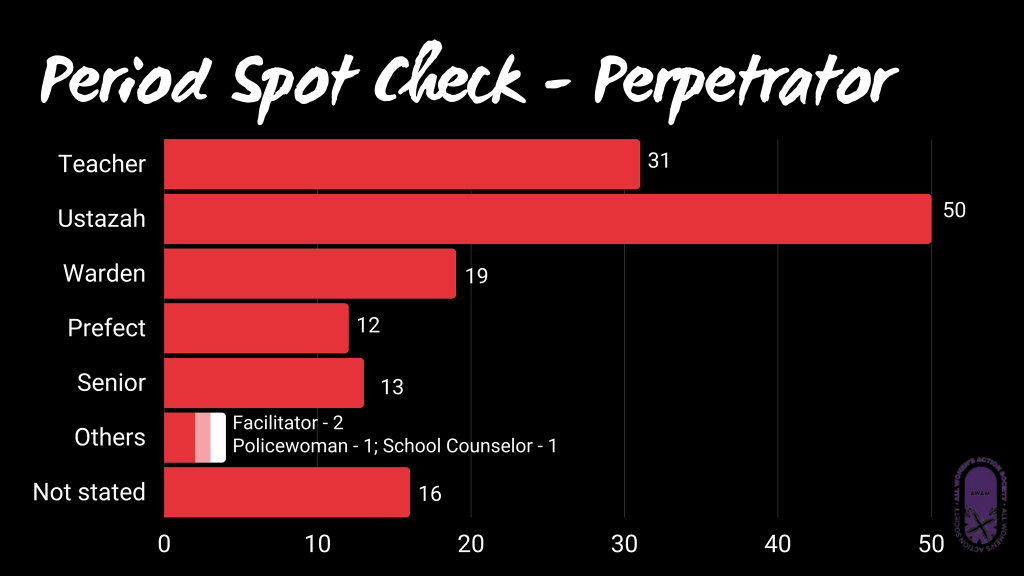

As I am reeling to understand the magnitude of misogyny on female bodies, I was astounded to learn about the practice of “period spot checks” in Malaysian schools two months ago (Alhadjri, 2021). As Muslim girls cannot pray while menstruating, religious teachers and even school prefects have resorted to making sure that these girls were in fact menstruating and not lying about it to avoid fasting and prayers. These period spot checks involved groping the student’s buttocks or vulva through clothing to feel for the sanitary pads or even asking the said student to show a piece of tissue with blood or her sanitary pad. A survey by AWAM (All Women’s Action Society Malaysia) revealed ustazahs (female religious teachers) to be the number one perpetrator of period spot checks (Figure 1) Again, this shows how internalised misogyny led women in positions of authority to believe that these girls could not be telling the truth and so violated these girls’ bodily integrity and autonomy. In an essence, the girls’ verbal assurance that they were menstruating was meaningless, and again we are seeing a recurring theme here of women’s voices being dismissed and disbelieved. Additionally, it is only on 20th June 2021, approximately two months after these stories of period spot checks surfaced online that the Malaysian Minister of Education, Datuk Dr Mohd Radzi Md Jidin, announced that they are in the final stages of establishing an independent committee to look into these period spot check allegations (Menon, 2021b). Shouldn’t this independent committee looking into these matters be already in place, instead of just being newly formed?

And while the story of the period spot checks is still unfolding, Malaysia was again shocked by a viral TikTok video by 17-year-old Ain Husniza Saiful Nizam on 23rd April 2021 on a male teacher making rape jokes in her class which had inspired her to start the #MakeSchoolaSaferPlace movement. Reactions to Ain’s video have been a mixture of disbelief to deep hatred with rape threats to Ain, who only wanted a safer schooling environment for all students (Lee & Singh, 2021). I admire what Ain is doing to end sexual harassment in schools and especially to have the strength to stand against many others who do not share the same views (to put it politely). Since these two incidents, many others have come forward telling their stories of period spot checks, sexual harassment, and public shaming in schools (Kwan, 2021; Teoh, 2021). As of 12th May 2021, the teacher accused of making the rape joke has been transferred to the state education department until the outcome of the police investigation is finalised (Menon, 2021a).

It makes my schooling experience seemed like a walk in a park by comparison.

More from Dr. Hannah Nazri here.

Ainslie, M. J. (2015). The 2009 Malaysian Female Circumcision Fatwa: State ownership of Islam and the current impasse. Women’s Studies International Forum, 52, 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2015.06.015

Al Jazeera. (2021, April). ‘Law against Islam’: French vote in favour of hijab ban condemned. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/4/9/a-law-against-islam

Alhadjri, A. (2021, April 22). Schoolgirls “shamed, groped and violated” in period spot checks. Malaysia Kini. Retrieved from https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/571658

Isa, A. R., Shuib, R., & Othman, M. S. (1999). The practice of female circumcision among Muslims in Kelantan, Malaysia. Reproductive Health Matters, 7(13), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(99)90125-8

Japan Times. (2021, January 12). Malaysia virus emergency suspends parliament for first time since 1969. Retrieved from https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2021/01/12/asia-pacific/malaysia-coronavirus-emergency/

Kwan, F. (2021, April 22). Period spot checks and groping of students still going on. Free Malaysia Today. Retrieved from https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2021/04/22/period-spot-checks-and-groping-of-students-still-going-on/

Lee, T. Y., & Singh, S. (2021, May 17). The cost of calling out a “rape joke.” BBC Asia. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/world-asia-57086480

Menon, S. (2021a, May 12). Teacher who allegedly made rape jokes in Ain Husniza’s class transferred. The Star Online. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2021/05/12/teacher-who-allegedly-made-rape-jokes-in-ain-husnizas-class-transferred

Menon, S. (2021b, June 20). Education Minister: Committee to investigate “period spot checks” in schools almost ready. The Star Online. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2021/06/20/education-minister-committee-to-investigate-039period-spot-checks039-in-schools-almost-ready

Mowat, H., McDonald, K., Dobson, A. S., Fisher, J., & Kirkman, M. (2015). The contribution of online content to the promotion and normalisation of female genital cosmetic surgery: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Women’s Health, 15, 110. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-015-0271-5

Pejabat Mufti Wilayah Persekutuan. (2019). Irsyad Al-Fatwa Siri ke-293: Benarkah Wanita Mempunyai 9 Nafsu dan 1 Akal? Retrieved June 27, 2021, from https://muftiwp.gov.my/artikel/irsyad-fatwa/irsyad-fatwa-umum/3157-irsyad-al-fatwa-293-benarkah-wanita-mempunyai-9-nafsu-dan-satu-akal

R.AGE. (2018). How female circumcision is still practised in Malaysia | The Hidden Cut. Retrieved June 27, 2021, from The Star Online website: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Q4_q8n45Ys&t=9s

Rashid, A., & Iguchi, Y. (2019). Female genital cutting in Malaysia: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open, 9(4), e025078. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025078

Rashid, A., Iguchi, Y., & Afiqah, S. N. (2020). Medicalization of female genital cutting in Malaysia: A mixed methods study. PLOS Medicine, 17(10), e1003303. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003303

Sharp, G., Tiggemann, M., & Mattiske, J. (2014). Predictors of Consideration of Labiaplasty: An Extension of the Tripartite Influence Model of Beauty Ideals. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 39(2), 182–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684314549949

Teoh, M. (2021, April 28). Protect our children from “period spot checks” and other harmful acts at school. The Star Online. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com.my/lifestyle/family/2021/04/28/protect-our-children

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()