In March 2020, I left my graduate study at Oxford and travelled home to Queens, NY.

At 3 pm, I opened the door into our living room to find a very quiet home. Like many immigrant families in Queens, we are nine living in a 2.5-bedroom apartment, ranging from toddlers to octogenarians; and occupancy is ten when I’m home. Though we are nine, everyone lives on a different schedule. Some work nights and some days. So, it’s very unusual to have a quiet home. I saw two figures lying on the living room floor, which has become an extension of everyone’s bedroom and my niece’s play area.

I cheerily exclaimed, “Hellooo! Everyone’s favorite sibling is here”. The two figures on the living room floor moved slightly and groaned. My mom was one of them and got up on her feet, struggling a lot more than the last time I saw her. Coughing and crouched with aches, she went into the kitchen, started making me a cup of Tibetan tea.

I found my two-year-old niece, Dawa, jumping excitedly while her cheeks were burning red. I hugged her and felt her running a high fever; nonetheless, she wanted to show me the new dances and songs she had learned from YouTube. She seemed different from the last time I was home. Her daily routine of going to parks, library, and napping with her grandparents has been interrupted with eight adults towering over her all day.

Dawa led me to the bed she shares with her parents. I found her parents coughing and lying on their backs. Dawa’s mom, Sonam, is a nurse at a city hospital in Brooklyn. She has been caring for COVID patients. Dawa’s dad, Tenzin, is my oldest brother. My two brothers, Tenzin and Nima, are NYC yellow cab drivers; they were still picking up unmasked passengers from airports and shuffling them around the city until their leasing company decided to close the week of March 23.

My younger sister, Dewa, sat up on her floor mattress and started taking a work call on patient updates. She is a research coordinator at a cancer hospital in Manhattan; she goes into the office every other day. Dewa put her call on mute and told me our older sister, Pema, a Nurse Practitioner at one of the largest city hospitals, has been isolated in a family friends’ basement because her symptoms were worse than others. Pema had been caring for COVID patients, working 60+ hours a week while commuting an hour each way on the subway between Queens and Manhattan.

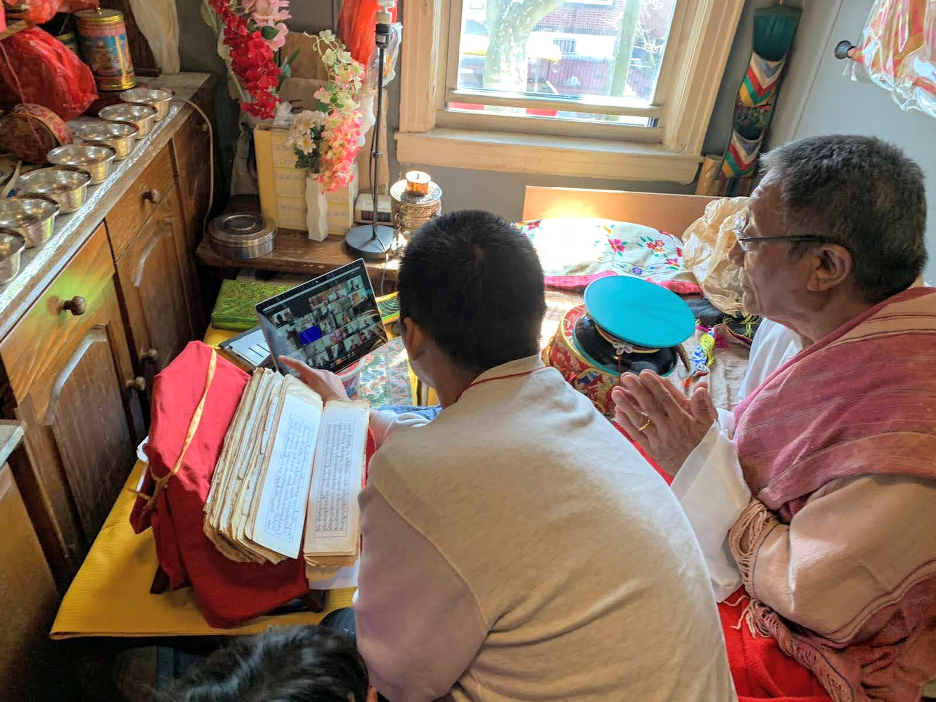

I found my dad and uncle in their closet-sized bedroom, which also doubles as our altar room. My dad is 79, and uncle is 80. They each gave me uthuk, an affectionate Tibetan greeting of pressing foreheads and asked me about my London journey to New York. As teenagers, the two were Tibetan guerilla warriors who made the decade-long harrowing journey, fighting Chinese soldiers on foot and horseback, from northeastern Tibet to Mustang, Nepal, and finally making a home in a refugee camp near Kathmandu. So, all my journeys pale in comparison. They spent their nomadic childhood shepherding yaks and sheep in Tibet, their young adult years guerilla fighting on the high plateau, their adult life portering goods up and down the mountains of Nepal, and now in their final act of life, they confined to this 6 x 8 ft room with a small window in Queens, NY.

As I sat down for tea with my mom, holding her arthritic, sandpaper-like palms, she told me that the older couple on the Upper Westside apartment’s she cleans five days a week had told her not to come to work anymore. She then showed me a pile of medical bills and late notice payments under my dad’s name, trying to understand what this all means. My 65-year-old mom’s lines have deepened on her face since I last saw her.

Tsechu Dolma spent the first half of her life as a stateless Tibetan refugee in Nepal moving from one refugee camp to another. At eleven, Tsechu fled the civil war in Nepal and sought political asylum in Queens, New York. She went on to receive a Bachelors in Environmental Science and Master’s in Public Administration degree from Columbia University.

Leveraging her education and experience, Tsechu returned to the refugee camps she left behind to make deep investments in small-scale, practical solutions to developmental challenges. She founded Mountain Resiliency Project, a social enterprise dedicated to building resilient refugee communities through women’s agribusiness. With 15,000 farmers, its proven track record has been recognized by the Asia Society Young Leaders, Forbes 30 under 30 in social entrepreneurship and Brower Youth Award. Prior to this, she worked as a natural resource management consultant for UNDP in Latin America and SIDS climate change strategist for the Timor-Leste Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Environment. Tsechu is a Fulbright Hillary Clinton Public Policy Fellow, Udall Scholar, Wild Gift Fellow and Echoing Green Fellow.

Tsechu is pursuing an MBA to broaden her abilities to advocate for and strengthen displaced communities. She believes social entrepreneurship is the tool to address inequities, development gaps, and improve livelihoods. She is a beekeeper, climber and farmer. When she is not in the mountains, you can find Tsechu buried in her books.

This blog originally appeared on HPHRxHealth Righters.org, an online collaboration of the Harvard Public Health Review, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and Health Righters.

Health Righters is a multidisciplinary publication exploring the intersection of healthcare and human rights, led in part by Harvard College.

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()