Matthews N, Carpenter C. Transnational corporations vs countries: who’s really got the power? HPHR. 2022;68.

The Global Health Debates is a video series aimed to democratise knowledge of complex global and public health topics into accessible summaries for a diverse audience. We believe that the world’s knowledge should be easily available and understood by all. We believe passionately in the power of knowledge to change attitudes, perspectives, and to inspire people to act in ways that accelerate the world’s growth into a more fair and equitable place.

The Global Health Debates aim to illustrate how issues in public health affect every aspect of day-to-day life. This video series aims to inform and engage the public about issues related to climate change, migration, transnational corporations and decolonisation through discussions with expert panellists. Each debate will define the relevant topics, highlight the latest developments in the field, and aim to underscore the importance of taking action to cause positive change by leaving the audience with actionable take-home points.

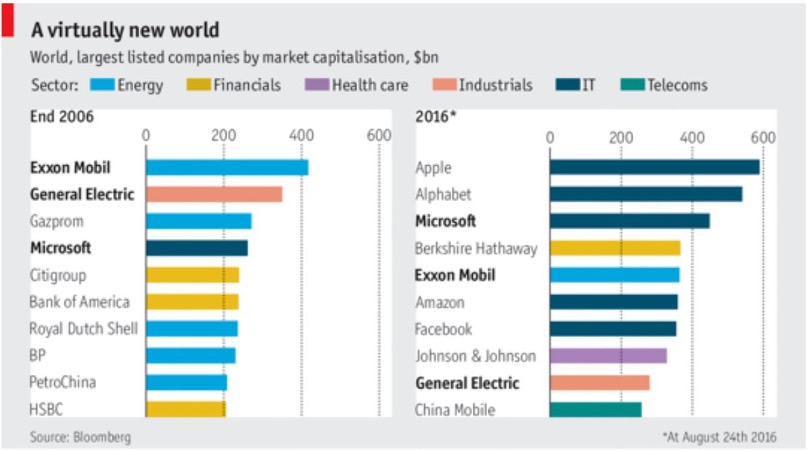

A transnational corporation (TNC) is any company that is involved in the production of goods and services in more than one nation. These companies are international and have branches across the globe.1 This type of organisational structure has become more common as globalisation has increased and the world is becoming more interconnected.2 We interact with transnational corporations daily, including companies such as Google, Apple, Amazon, Walmart, McDonald’s, Macy’s, Facebook, ExxonMobil, Johnson & Johnson, and General Electric.3

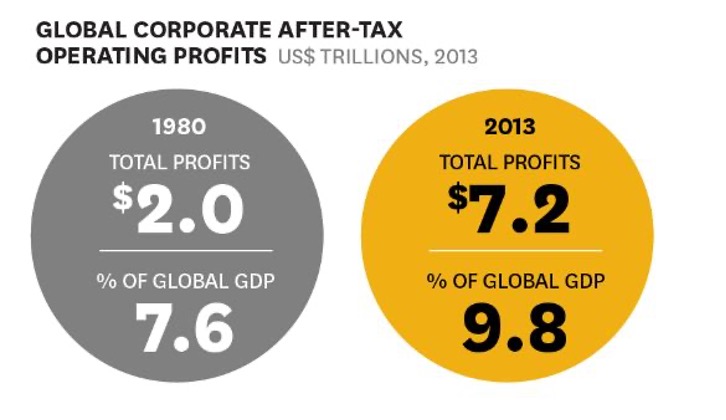

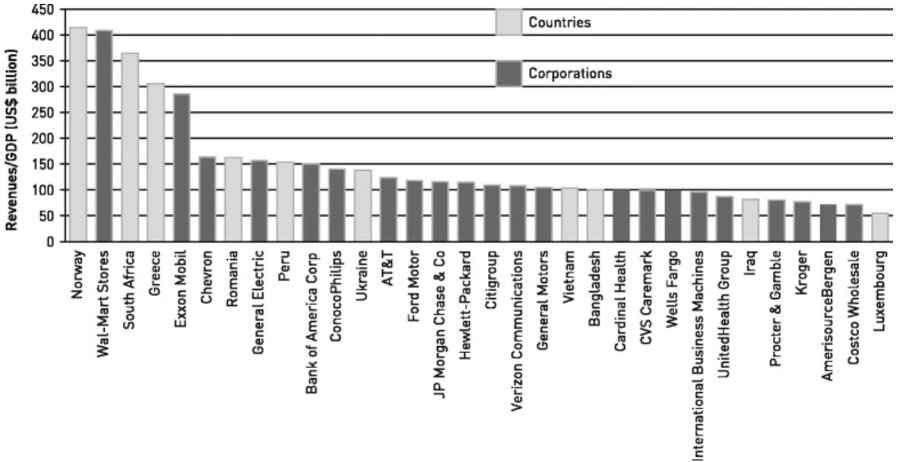

In many cases, transnational corporations have as much (if not more) power and influence than many national governments: Of the 100 highest revenue earners in 2014, 63 are transnational corporations and only 37 are governments.4 According to the World Economic Forum, fewer than 10% of the world’s publicly traded companies account for more than 80% of all profits.5 This gives the highest-earning companies a disproportionate influence over public policy decisions.4

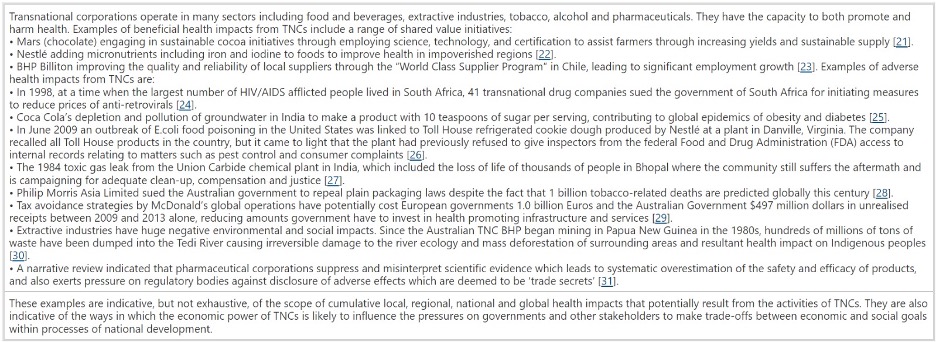

By nature, TNCs are neither moral nor amoral. They exist as creatures of the state, operating within the frameworks and guidelines created for them. In many countries, TNCs are the primary drivers of foreign investment and job creation. They can be the reason large amounts of money enter nations that are struggling economically. Their presence in such countries can lead to improvements in employment opportunities, developments in education and infrastructure, and better health service provision.4 However, on the other hand, the massive power and wealth that TNCs consolidate allows them to skirt local rules and regulations to create dangerous situations. In countries with poverty and poor regulations, TNCs have been known to commit human rights violations, environmental atrocities, and break labour laws all in the name of profits. These behaviours are directly harmful to health and can have lasting negative impacts on local communities.6 One example of predatory behaviour is when Coca Cola used up very limited fresh water in India to make soda instead of redirecting the water to the local people. Coca Cola continued to exploit the local people by taking advantage of their thirst and selling them soda that contained at least 10 grams of sugar leading to increases in obesity and diabetes.7

Similarly, the Australian company BHP dumped toxic waste products into the Tedi River in Papua New Guinea completely ruining the local ecosystem by causing massive deforestation.4 These travesties underscore the need for more stringent regulatory policies and frameworks to hold TNCs accountable. However, this is much easier said than done as the cumulative health impacts of these organisations are difficult to quantify in real-time.4 Furthermore, because TNCs are often decentralised, it is much more challenging to determine which nation ought to be the principal regulator. Lastly, regulation is difficult because of unequal power dynamics. Low and middle-income countries (LMICs) may feel scared and unable to fight back against TNCs with better regulation as they do not want to lose their primary sources of investment and revenue.6

Despite these challenges, we must continue to affirm the three pillars of the United Nation’s Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: 1) the state is responsible for protecting human rights by monitoring transnational corporations 2) corporations must abide by standards 3) victims have rights to remedy when these standards are violated.8 Using these guidelines, we must ensure that countries hold TNCs accountable for their violations – such as exploiting cheap labour, irrevocably damaging the environment, and introducing many unhealthy foods into local diets leading to health problems.9 Particularity, LMICs have to be empowered to fight back against TNCs as they are often sold the myth of globalisation. In practice, this only leads to the exploitation of both people and natural resources, as explained by the resource curse which explains how countries such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Mozambique remain poor despite their large swaths of minerals and precious metals.10,11

Despite their tendencies to chase profits, there is still optimism that TNCs may be becoming more morally conscious as recent ideas such as impact investing have gained momentum. This is the belief by investors that their money should be invested into companies that have clear ethical boundaries and are committed to creating greater good for all people.12 Similarly, there has been greater talk of breaking up monopolies. This will ensure that no single company dominates the market and will lead to a more proportionate distribution of wealth and influence.13,14 Overall, we hope that the adoption of more ethical investment strategies and increased government regulations will prevent TNCs from causing harm in LMICs.

Figure 1. Changes in the World’s Largest TNCs over a Decade5

Figure 2. Concentration of TNCs in Ten Countries15

Figure 3. Increases in Global Corporate Profits over Three Decades16

Figure 4. Comparing TNCs to Countries4

Figure 5. Examples of TNCs’ Impact on Health4

The author has no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

We gratefully acknowledge Mr. Douglas A. Johnson, Dr. Bronwyn King, Prof. John E. McDonough, Ms. Johanna Ralston, Mr. John D. Scott for their participation as panelists in The Global Health Debates: Transnational Corporations and Regulation, which made this project possible. We also acknowledge the valuable contributions of our Producer, Dr. Circe Gray Le Compte, and Associate Producers, Ms. Hassina Bahadurzada, Mr. Sid Gugale, Ms. Sharon Hancart, and Dr. Rhea Saksena, who contributed to the initial focus group on transnational corporations and regulation.

Dr. Matthews is a National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Academic Clinical Fellow in Emergency Medicine, passionate about global health, equity and human rights. Her research interests include developing global health education, migrant health, mental health, elderly health, medical ethics, and law. She is also Executive Producer of the Great Health Debates. Dr. Matthews has long advocated integrating components of global health education into medical school curricula.

Dr. Carpenter serves as Co-Editor-in-Chief of HPHR Journal, and is Founder and Co-CEO of The Boston Public Congress of Public Health. She is also Executive Producer of the Great Health Debates. She is a neurosurgeon-in-training, bio and social entrepreneur, educator, and social justice advocate.

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()