Rae Myerss J, Telford Rose S. A preliminary report of trauma impact on language skills in biliingual adults: A case for trauma-informed services . HPHR. 2022;62.10.54111/0001/JJJ1

This study explores the reported impact of trauma on language skills in bilingual adults and show language fluency in both languages spoken may be impacted by traumatic experiences including COVID-19.

In her memoir, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, the author, poet, civil rights activist, and orator Maya Angelou recounts a profound childhood trauma that led to her selective mutism. The trauma Maya experienced so profoundly affected her physiology that she rendered herself incommunicable for five years. This illustration highlights the relationship between trauma and language. Trauma, defined as “exposure to a single or multiple events or experiences that overwhelm (overload) the brain, and includes the internalization of feelings of powerlessness, helplessness, and loss of safety,” can have detrimental impacts on one’s linguistic abilities7.

A burgeoning body of research supports that people who experience trauma are at higher risk for having communication disorders, smaller vocabularies, and poorer expressive, receptive, and socio-pragmatics language skills). 6-9,14 Further, Busch & McNamara3 argue that trauma may limit one’s “inclination to learn languages, to use, retain, or abandon a particular language.” Specifically, the underlying processes that promote language skills such as memory, attention, executive functioning, linguistic processing, and other cognitive functions are often negatively impaired as a result of trauma 5,14. Consequently, the importance of trauma-informed services has garnered more attention in recent years, with COVID-19 serving as one of its catalysts for prominence. As our understanding of the relationship between trauma and cognitive- communication is evolving, it is crucial to explore how trauma can affect various populations we serve–particularly groups that have historically marginalized members, as they are at greater risk for cognitive-communication impairment and exposure to trauma. The current descriptive study explores the perception of recent traumas on the bilingual abilities of simultaneous and sequential bilinguals with implications for culturally-responsive transdisciplinary intervention.

Survey data on 212 Spanish-speaking bilingual adults (ages 21-60) was examined as part of a larger ongoing study examining posttraumatic stress, COVID-19, and cognitive-linguistic skills in Spanish-speaking bilinguals. The survey was developed based on questions from survey studies found to be effective in capturing meaningful bilingual-related information.5 Research has also shown self-reports of language fluency and usage among US Spanish/English bilingual adults are reliable indicators of language ability in this population.12 Responses from demographic, cognitive-communication, and trauma-related questions were used to conduct a descriptive analysis concerning their current (within 5 years), most impactful trauma. Participants’ characteristics are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Participant Characteristics

Characteristic | Participants (N = 212) | ||

Age – M (SD) |

34.94(6.72) |

| |

Gender – n (%) Men Women |

119 (56) 93 (44) |

| |

Hispanic Origin – n (%) Yes No |

111 (48) 102 (52) |

| |

Race – n (%) American Indian or Alaska Native Asian Black or African American Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander White Prefer not to say |

7 (3) 20 (9) 44 (21) 7 (3) 103 (49) 31 (15)

|

| |

Education – n (%) High School Some High School Bachelor’s Degree Master’s Degree PhD or higher Associate’s Degree Trade School Prefer not to say |

6 (3) 5 (2) 83 (37) 81 (36) 25 (11) 10 (4) 1 (<1) 1 (<1) |

| |

Primary Language – n (%) English Spanish Both Other* |

161 (76) 48 (23) 2 (<1) 1 (<1)

|

| |

The survey took approximately 20 minutes to complete and was provided in English and Spanish. Participants gave informed consent prior to completing the survey (also provided in English and Spanish). Upon successful completion of a survey, participants were compensated via a $15 gift card. This study was reviewed and approved by the University of the District of Columbia’s institutional review board.

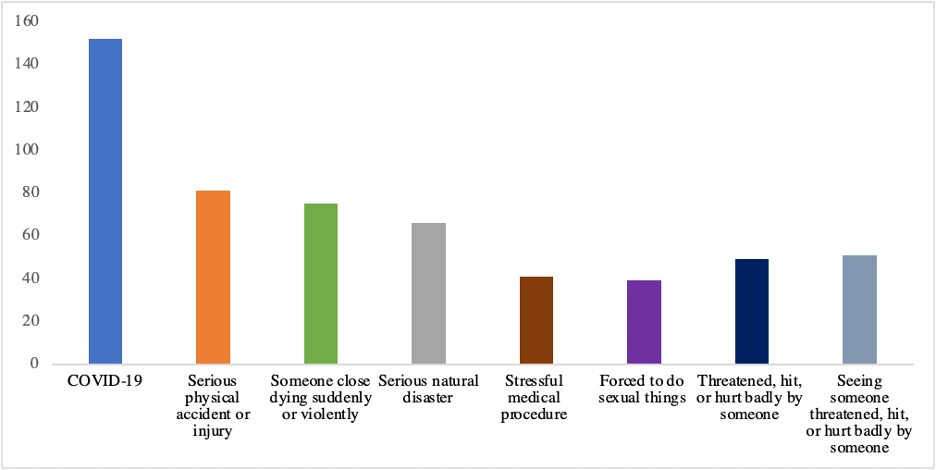

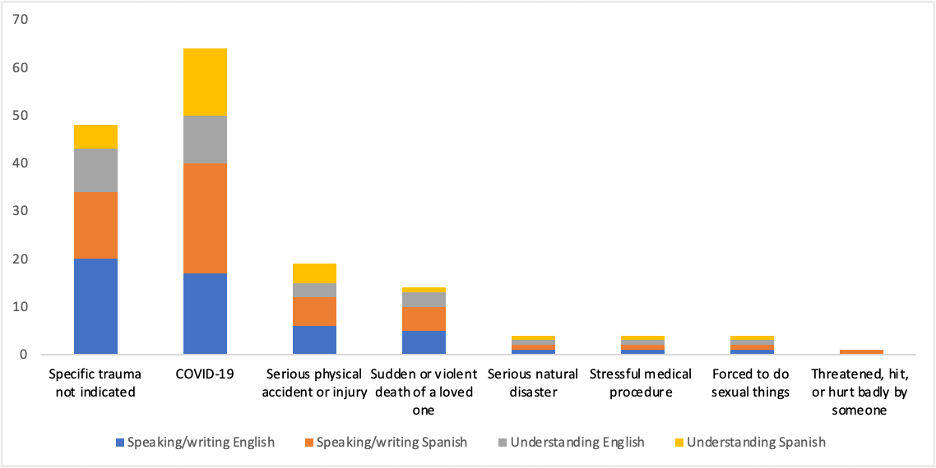

Participants were asked to indicate if they “experienced mental, physical, or emotional trauma within the last 5 years” based on established traumatic stressors (e.g., “threatened, hit, or hurt badly by someone”) and COVID-19. Almost all the participants endorsed at least one traumatic experience (98%), with 56% of those participants experiencing multiple traumas. The percentages were reduced to 78% and 36%, respectively, when COVID-19 was removed. Thirty-three percent of participants indicated their traumatic experience was currently impacting their language skills, and of those experiences, 44% were attributed to COVID-19. Lastly language fluency (speaking/writing) in Spanish was the most reported language skill impacted (77%) closely followed by language fluency in English (76%). Figures 1 and 2 provide additional details regarding participants’ history of trauma and its impact on their language skills.

Figure 1. Reported Traumatic Experiences

N = 212; One reported traumatic experience , n = 92; more than one reported traumatic experience, n = 115; no reported traumatic experience, n = 5 ; Number of traumatic experiences reported in sample: COVID-19, 152; Serious physical accident or injury, 81; Someone close dying suddenly or violently, 75; Serious natural disaster, 66; Stressful medical procedure, 41; Forced to do sexual things, 39; Threatened, hit, or hurt badly by someone, 49; Seeing someone threatened, hit, or hurt badly by someone, 51.

Figure 2. Reported Trauma Currently Impacting Language Skills

N = 70; Trauma type: Specific trauma not indicated (n = 22); COVID-19 (n = 31); Serious physical accident or injury (n = 8); Someone close dying suddenly or violently (n = 5); Serious natural disaster (n = 1); Stressful medical procedure (n = 1); Forced to do sexual things (n = 1); Threatened, hit, or hurt badly by someone (n = 1). Not shown as n = 0, Seeing someone threatened, hit, or hurt badly by someone; Language skill impacted (% of participants): Speaking/writing English (76%), Speaking/writing Spanish (77%), Understanding English (41%), Understanding Spanish (40%).

These preliminary research findings indicate that a staggering one-third of participants perceived that their recent traumas negatively impacted their speaking and writing ability in both languages. This finding supports the existing literature on trauma and language 3,13. In addition, the findings also demonstrate that an overwhelming majority whose linguistic skills were impacted found that both languages were impaired. Therefore intervention in both languages may be optimal for remediation. As speech-language pathologists are specialists for individuals who have or are at risk for language disorders, a transdisciplinary approach with a team of other specialists such as psychologists, occupational therapists, and social workers is recommended to optimize the success of the clients/patients. Given the sensitive nature of trauma it is also pertinent that healthcare clinicians be culturally responsive and aware to address the unique needs of bilingual individuals and employ cultural and linguistic brokers when there is a mismatch between the client and clinician’s language and culture10.

A transdisciplinary approach to intervention is optimal7. The envisioned transdisciplinary team would convene after the completion of a biopsychosocial evaluation by the psychologist. The rationale for establishing the team would be to ensure that all parties utilize the tools and expertise of each professional in a meaningful way to enhance their own discipline-specific work and provide holistic trauma-informed services to the client. A cultural and linguistic broker must serve on the team pre-evaluation to provide the clinicians with pertinent information regarding the client’s specific language(s) and cultural norms that differ from the mainstream culture. The psychologists or trauma trained licensed social worker would inform the other clinicians on identifying “trauma responses,” “building relationships of trust and safety,” and reducing triggering repeated trauma with the specific client7. The speech-language pathologist would support the clinical social worker or psychologist by addressing needs for learning new vocabulary for expressing feelings, thoughts, and ideas or who have trauma-related socio-pragmatic communications challenges. In sum, the team would begin by sharing their roles and responsibilities for the client and then, as a team, construct an integrated plan for addressing the client’s needs from a holistic perspective which may enhance overall treatment efficacies.

Ongoing research concerning culturally -responsive and trauma-informed care for bilingual individuals who experience trauma is essential. As we learn more about the impact of trauma on language, it is important to understand the profiles of individuals with trauma in order to make meaningful strides in the field.

This project is supported by a multicultural activities grant awarded by the American Speech Language and Hearing Association to Drs. Jennifer Rae Myers and Sulare Telford Rose. The authors would like to thank the participants for their time and effort in completing the survey.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be interpreted as a potential conflict of interest.

1Boroditsky L. How language shapes thought. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-language-shapes-thought/. Published February 1, 2011. Accessed May 31, 2022.

2Brown B. Atlas of the Heart: Mapping Meaningful Connection and the Language of Human Experience. London, England: Vermilion; 2021.

3Busch B, McNamara T. Language and trauma: An introduction. OUP Academic. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amaa002. Published April 17, 2020. Accessed May 31, 2022.

4Gibson TA, Peña ED, Bedore LM. The receptive-expressive gap in bilingual children with and without primary language impairment. American journal of speech-language pathology. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6380504/. Published November 2014. Accessed May 31, 2022.

5Hayes JP, VanElzakker MB, Shin LM. Emotion and cognition interactions in PTSD: A review of neurocognitive and neuroimaging studies. Frontiers. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnint.2012.00089/full. Published January 1, 1AD. Accessed May 31, 2022.

6Hine S. Untangling the trauma-speech connection. https://columbian.gwu.edu/. https://columbian.gwu.edu/untangling-trauma-speech-connection. Published April 10, 2020. Accessed May 31, 2022.

7Hyter YD. Childhood maltreatment consequences on Social Pragmatic Communication: A systematic review of the literature. ASHA Wire. https://pubs.asha.org/doi/epdf/10.1044/2021_PERSP-20-00222. Published December 22, 2020. Accessed May 31, 2022.

8Vukovic,M.,Vuksanovic, J, Vokovic, J. Comparison of the recovery patterns of language and cognitive functions in patients with post-traumatic language processing deficits and in patients with aphasia following a stroke. Journal of communication disorders. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18571195/. Published 2008. Accessed May 31, 2022.

9Wild, J. & Gur,RC..Verbal memory and treatment response in post-traumatic stress disorder. Br J Psychiatry. https://www.psy.ox.ac.uk/publications/382826. Published 2008. Accessed May 31, 2022.

10Kaplan I, Stolk Y, Valibhoy MC, Tucker A, Baker J. Cognitive assessment of refugee children: Effects of trauma and New Language Acquisition: Semantic scholar. undefined. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Cognitive-assessment-of-refugee-children%3A-Effects-Kaplan-Stolk/facdbe518d3ae2c858eac0e6da6e4ec2011f612b. Published January 1, 1970. Accessed May 31, 2022.

11Kartal D, Alkemade N, Kiropoulos L. Trauma and mental health in resettled refugees: Mediating effect of host language acquisition on posttraumatic stress disorder, depressive and anxiety symptoms: Semantic scholar. undefined. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Trauma-and-Mental-Health-in-Resettled-Refugees%3A-of-Kartal- Alkemade/4b0586da1cac9e83353a9e0b741ebfe42bb48687. Published January 1, 1970. Accessed May 31, 2022.

12Marian V, Marian V, Blumenfeld HK, University N, Kaushanskaya M. The language experience and proficiency questionnaire (LEAP-Q): Assessing language profiles in Bilinguals and multilinguals. ASHA Wire. https://pubs.asha.org/doi/10.1044/1092-4388(2007/067). Published April 12, 2018. Accessed May 31, 2022.

13Myers JR, Solomon NP, Lange RT, et al. Analysis of discourse production to assess cognitive communication deficits following mild traumatic brain injury with and without posttraumatic stress. ASHA Wire. https://pubs.asha.org/doi/10.1044/2021_AJSLP-20-00281. Published December 21, 2020. Accessed May 31, 2022.

14Papini S, Yoon, Rubin M, Lopez-Castro T, Hien DA. Linguistic characteristics in a non-trauma-related narrative task are associated with PTSD diagnosis and symptom severity. Psychological trauma : theory, research, practice and policy. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25961121/. Published 2015. Accessed May 31, 2022.

Jennifer Rae Myers is clinical research scientist at a digital health company. As a speech-language pathologist and neuropsychologist, her interests include the cognitive-communication impact of trauma, cognitive health disparities, and research inclusivity. In 2019, she founded a grassroots nonprofit, RB Foundation, that provides free expression-focused programs in underserved communities. Recently, she co-created ‘Culturally S.M.A.R.T.’, a program which provides culturally responsive training and research mentorship to underrepresented clinical graduate students.

Sulare Telford Rose is an assistant professor of speech-language pathology at the University of the District of Columbia. She serves as the professional development manager for the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association’s Special Interest Group-17, Global Issues in Communication Sciences and Related Disorders, and serves on the board of directors for the National Black Association of Speech-Language and Hearing (NBASLH). Sulare is keenly interested in exploring culturally responsive assessment and intervention methods for addressing the needs of non-mainstream populations, particularly those from Spanish and Caribbean English Creole-speaking backgrounds. Her most recent research explores providing evidence-based trauma-informed care to bilingual clients. She is the co-creator of ‘Culturally SMART,’ a program that provides culturally responsive training and research mentorship to underrepresented graduate students in speech-language pathology and related disciplines.

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()