Sifat M, Chiang S, Amin N, Traore S, Irfan A, Green K. Beyond performative activism: an exploration of motivators to participate in anti-racist activism through the lense of self-determination theory. HPHR. 2021;35.10.54111/0001/AAA3

Social media allows individuals to participate in social activism and contribute to the discourse around societal and health inequities. Given the different roles social media plays in social activism, there is a need to investigate further the underlying motivations and the mechanisms by which people choose to partake in social media activism and other civic actions. The present study applied the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) to understand motivators toward activism on social media platforms.

Cross-sectional, convenience sampling, and logistic regression.

In a sample of 171 adults, we found that one’s sense of autonomy was associated with signing petitions (AOR= 1.40, p<.001) and sharing on social media (AOR=1.62, p<.001) regarding the topic of police brutality. Sense of competency and autonomy were associated with signing petitions (AOR=1.35, p <.001and AOR=1.32, p=0.001 respectively) and sharing news on social media (AOR =1.32, p< 0.001 for competency and AOR=1.45, p =.001 for autonomy), as they related to violence against Black Americans. When examining discrimination against Black Americans, we found that higher self-perceived competency toward signing petitions (AOR=1.39, p<.001), sharing news on social media (AOR=1.23, p=0.011), and discussing with friends and family (AOR=1.86, p=.001) is associated with the act of actually doing so. Sharing on social media was associated with increased odds of donations (AOR=5.09, p<.001) and of having discussions with family and friends (AOR=5.04, p=.007) on topics related to discrimination, violence, or police brutality toward Black Americans.

These results can help social movements inform their communications and social media activism strategies by pairing action steps with social media outreach efforts.

Through literature, art, donations, protests, and more, social activism has been used throughout history to drive reform. Most activism is concerned with creating or contributing to social, political, or economic change. In the era of social media and computer-mediated communication, people can discuss and disseminate new information at an unprecedented speed. This shift in communication has allowed a diverse array of individuals to participate in social activism and contribute to the discourse around societal and health inequities (Smith, Williamson, & Bigman, 2020; Byrd, Gilbert, & Richardson). Because social media – specifically social media activism – is an essential tool in modern-day activism, it is relevant to understand the motivations behind social media activism and subsequent engagement in other forms of activism (Bennett & Segerberg, 2011). Doing so is critical, as, in the short and long term respectively, it can help increase civic engagement and advocacy while addressing structural factors that perpetuate racism in both the short and long term.

Existing research has suggested ways by which social media can influence social activism positively or negatively. Social media can promote collective action by providing information not available through other media channels, facilitating demonstrations offline, creating opportunities to engage in discussions with other social media users, and finding social support (Bennett & Segerberg, 2011). Despite those benefits, the growth in activism using social media is sometimes criticized as slacktivism, defined as “low-risk, low-cost activity via social media whose purpose is to raise awareness, produce change, or grant satisfaction to the person engaged in the activity” (Rotman et al., 2011).

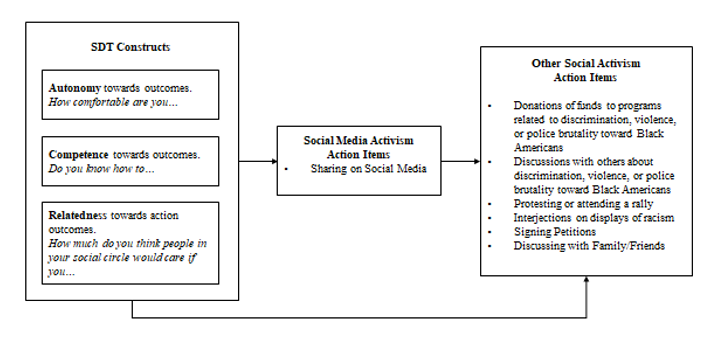

For the purpose of this pilot study, a conceptual model relating Self-Determination Theory (SDT) constructs and social activism, (shown in Figure 1) was used. We assume the SDT constructs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness directly result in social media activism, particularly sharing on social media. Social media activism was then assumed to be directly related to higher-level social activism actions like donations, discussions with peers, attending rallies and more. We also assumed another, more direct avenue between SDT constructs and higher-level social activism actions. In this pathway, the constructs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness would directly result in higher-level social activism actions. Understanding the intersection of social media and social activism is critical, as social activism is a driving force behind public policy changes and dismantling structural racism and health inequities (APHA, 2020).

This paper comes at the height of the racism pandemic (APA, 2020). Given the recent murder of George Floyd which sparked worldwide protests that brought increased attention to the discrimination Black people face in their daily lives, this study into motivators for activism is timely (Godlee, 2020). Research shows that Black people are more likely than White people to experience police brutality, with more than 200 Black lives lost for every one White life (Boyd, 2018), and that this correlates to detrimental health effects (Alang et al., 2017). In addition to the more apparent effects of worsened physical health for direct victims of police brutality, communities that witness killings of unarmed Black American have higher rates of depression and PTSD (Bor et al., 218; Laurencen & Walker, 2020). Racism also persists on a less institutional level– such as in the case of discrimination perpetrated by civilians–but results in loss of life and worsened health all the same. In recent news, for example, civilians shot 25-year old Ahmaud Arbery while he was out on a jog. His murder, along with countless others, renewed efforts in combating these issues of racism on social media in the United States.

This pilot study represents a timely effort to better understand the mechanisms by which social media facilitates actions related to the current anti-racism movement through the lens of Self-Determination Theory (SDT). Specifically, the study is guided by two research questions: 1) what is the association between slacktivism and other forms of activisms (e.g., signing petitions) related to the racism pandemic and 2) are the constructs of Self-Determination Theory (autonomy, competency, and relatedness) associated with actual action regarding combating racism against Black Americans? Through this study and its findings, social justice movements will be able to better engage individuals by tailoring their activities in accordance with the motivators most closely associated with activism.

Some research has found that by engaging in low-risk, low-cost activities on social media, individuals’ inner urge to participate in social activism may be satisfied, resulting in no further actions (Kristofferson, White, & Peloza, 2014). Kristofferson and colleagues (2014) found that people who engage in private action donated more money to a cause and were more likely to sign petitions than those who publicly endorsed the cause. They also found that public endorsement of a cause satisfied a person’s impression motive, which led to a lower likelihood of providing meaningful support for a cause, whereas private support led to higher consistency motives and higher levels of meaningful support for a cause. However, it is also possible that engaging in social media motivates people to take further action. For example, Lee & Hsish (2013) found that engaging on social media may inspire people to act; in this case, it was associated with donating money to charities after earthquakes or other disasters. Given the different roles social media plays in social activism, there is a need to investigate further the underlying reason and the mechanism in which people choose to partake in social media slacktivism as well as other types of civic actions.

H1: Engaging in social media activism is not associated with other forms of activism.

The Self-Determination Theory (SDT) posits that motivation toward a behavior stems from three innate and psychological needs: competence, autonomy, and psychological relatedness (Deci & Vansteenkiste, 2004). The construct of competence refers to the feeling that a person has a sense of mastery in their actions. Relatedness refers to the sense of belonging that one feels concerning others; for example, it encompasses the feeling that one matters to other people, that they are cared for or connected to other people, and a sense of mutual concern. Autonomy refers to self-endorsed behavior, that one feels able to choose in their actions, and that their actions are self-initiated (Deci & Vansteenkiste, 2004). SDT has been employed in various settings to explain motivation related to work, exercise, behavior change (Deci & Ryan, 2012), and environmental activism (Sheldon et al., 2016). This same theory can be applied to understand motivation-related social media activism further. The present pilot study applied the SDT and used the racism-related social movement as an example to further understand social activism on social media.

H2: The autonomy, relatedness, and competency that one feels toward engaging in activism are positively associated with actual involvement in activism regarding police brutality, discrimination, and violence toward Black Americans.

Recruitment for the study occurred between July and September 2020. Participants (N = 171) were recruited on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and University departmental listservs, through snowball sampling. To be eligible for the study, participants had to be 18 years of age or older. Participants consented online before the beginning of the survey. This study was approved by the University of Maryland College Park Institutional Review Board (IRB # 1614530-1).

The main independent variables of interest were autonomy, competency, and relatedness toward social activism regarding police brutality, discrimination, and violence toward Black Americans. We also measured one’s autonomy, competency, and relatedness toward sharing these topics on social media. These were measured on a 10-point Likert scale (ranges 1-10), with higher scores indicating higher autonomy, competency, and relatedness. Questions were asked with the same question stem and different prompts as follows – competency toward behaviors was measured with one item: “do you know how to;” autonomy was assessed with “how comfortable are you to.” Relatedness was assessed by asking, “how much do you think people in your social circles would care if you” 1) share information on social media 2) donate money to a cause you care about 3) participate in the form of activism regarding a) police brutality b) discrimination (perpetrated by civilians) c) violence (perpetrated by civilians) toward Black Americans, if you wanted to.”

Outcome variables, what we define as partaking in social media activism for this study, were measured as binary outcomes (yes/no), whether one participated in the following kinds of activism related to police brutality, discrimination, or violence against Black Americans-donation of funds to related programs, sharing information on social media, having discussions with other people, protesting or attending a rally, and interjecting when other people display signs of racism, or not. Demographics measured ethnicity, age in years, gender (male, female, non-binary), household income (<$25,000 to >$100,000), and education level (high school diploma to doctoral degree).

Analyses for this study were conducted using SPSS v25. Descriptive statistics were computed for participant characteristics. Pearson’s correlations were examined between the three constructs of self-determination theory, for each outcome, sharing about these topics on social media, participating in activism regarding police brutality, discrimination, and violence against Black Americans. To assess the association between SDT constructs and outcome variables, logistic regression models were constructed for each topic assessed (i.e., police brutality, violence, or discrimination against Black Americans). Both unadjusted bivariate logistics regression and multivariable logistics regression models were computed. Only results for the adjusted models are presented due to similar results between unadjusted and adjusted models.

Outcome variables, what we define as partaking in social media activism for this study, were measured as binary outcomes (yes/no), whether one participated in the following kinds of activism related to police brutality, discrimination, or violence against Black Americans-donation of funds to related programs, sharing information on social media, having discussions with other people, protesting or attending a rally, and interjecting when other people display signs of racism, or not. Demographics measured ethnicity, age in years, gender (male, female, non-binary), household income (<$25,000 to >$100,000), and education level (high school diploma to doctoral degree).

Table 1 presents the overall baseline sample characteristics of this pilot study. The sample (n= 171) was, on average, 28 years old (standard deviation 6.68). They were primarily female (77%), white (44%), or South Asian (30%), with a bachelor’s degree (36%) or a master’s degree or professional degree (49%). The majority of the sample also reported a higher household income than $50,000 (71%). All participants reported that they use social media, specifically Facebook (86%), Twitter (50%), Instagram (92%), and TikTok (24%).

Table 1. Demographics of Sample

Characteristics | %/M (SD) | |

Sex | ||

Female | 77% | |

Male | 20% | |

Non-binary | 3% | |

Age | 28.02 (6.68) | |

Race Ethnicity | ||

Asian | 11% | |

South Asian | 30% | |

Black | 7% | |

White | 44% | |

Latinx | 4% | |

Other | 4% | |

Education | ||

High school diploma | 7% | |

Associate degree, or some college | 8% | |

Bachelor’s degree | 36% | |

Master’s degree | 32% | |

Doctoral Degree | 17% | |

Household Income | ||

<$25,000 | 9% | |

$25,000 – $34,999 | 8% | |

$35,000 – $49,999 | 6% | |

$50,000 – $74,999 | 23% | |

$75,000 – $99,999 | 12% | |

>$100,000 | 36% | |

Not Sure | 6% | |

Mean autonomy, or participants’ comfort level, towards sharing information in general on social media, was 9.41 on a 10-point scale. Participants’ mean autonomy scores towards social activism related to police brutality, discrimination towards Black Americans, and violence towards Black Americans, ranged from 7.54 to 7.82. The mean competency score –score quantifying knowledge levels towards a certain action– of sharing information generally on social media was 8.19. Participants’ mean competency scores towards social activism related to the three activism areas ranged from 7.59 to 7.85. Participants’ mean relatedness score for sharing information in general on social media was 5.33. These relatedness scores, which quantified how much they thought people in their social circles would care if they engaged in an action, ranged from 4.68 to 4.74 in reference to social activism centered on the three issue areas.

When asked about sharing behavior, the majority of participants reported that they had shared on social media regarding the topics of police brutality (74%), discrimination toward Black Americans (70%), and violence towards Black Americans (57%). Similarly, the majority of participants said that they had signed petitions on those same subjects for police brutality (78%), discrimination towards Black Americans (60%), and violence toward Black Americans (59%). Almost all participants reported having discussed the following topics of police brutality (97%), discrimination towards Black Americans (94%), in violence toward Black Americans (89%) with family or friends.

Table 2. Descriptive Table of Self Determination Theory Constructs

| Self Determination Theory Constructs | %/M(SD) |

Autonomy (1-10) | |

Share information on social media | 9.41 (1.31) |

Participate in activism regarding police brutality | 7.82 (2.41) |

Participate in activism regarding discrimination toward Black Americans | 7.67 (2.37) |

Participate in activism regarding violence toward Black Americans | 7.54 (2.44) |

Competence (1-10) | |

Share information on social media | 8.19 (2.37) |

Participate in activism regarding police brutality | 7.59 (2.49) |

Participate in activism regarding discrimination toward Black Americans | 7.85 (2.40) |

Participate in activism regarding violence toward Black Americans | 7.72 (2.44) |

Relatedness (1-10) | |

Share information on social media | 5.33 (3.09) |

Participate in activism regarding police brutality | 4.74 (2.97) |

Participate in activism regarding discrimination toward Black Americans | 4.70 (2.91) |

Participate in activism regarding violence toward Black Americans | 4.68 (2.92) |

Ever shared topic on social media regarding following topics | |

Police Brutality | 74% |

Discrimination toward Black Americans | 70% |

Violence toward Black Americans | 57% |

Ever signed petitions regarding following topics | |

Police Brutality | 78% |

Discrimination toward Black Americans | 60% |

Violence toward Black Americans | 59% |

Ever discussed the following topics with family or friends | |

Police Brutality | 97% |

Discrimination toward Black Americans | 94% |

Violence toward Black Americans | 89% |

Next, we examined the association between each SDT construct for each outcome — competency, autonomy, and relatedness toward any type of activism regarding police brutality, discrimination, and violence toward Black Americans. Results, shown in Table 3, indicate multiple significant correlations, all significant at a p<.001 level. For predictors related to police brutality, significant correlations between competency and autonomy (r=.481). The construct of competency toward activism against police brutality was also correlated with competency and autonomy toward activism against discrimination (r= .854 and .438) and violence (r= .816 and .449) perpetrated by civilians. Similarly, autonomy towards activism against police brutality was correlated with competency and autonomy toward engaging in activism for discrimination (r=.444 and .916) and violence (r=.398 and .916) perpetrated by civilians. Relatedness regarding anti-police brutality activism was correlated with measures of relatedness towards activism against discrimination (r=.952) and violence (r=.944) perpetrated by civilians. Competency toward activism opposing discrimination by civilians was correlated with autonomy toward anti-discrimination activism (r=.476), competency toward anti-violence activism (r=.912), and autonomy for activism against violence (r=.480). Autonomy toward activism against discrimination was correlated with autonomy (r=.432) and competency (r=.945) for engaging in anti-violence (perpetrated by civilians) activism. Relatedness measures toward anti-discrimination activism was correlated with relatedness measures toward anti-violence activism (r=.978).

Table 3: Correlations Between SDT Measures (n=171)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

1. Competency toward activism regarding police brutality | 1 | .481** | -0.048 | .854** | .438** | -0.024 | .816** | .449** | -0.021 |

2. Autonomy toward activism regarding police brutality | 1 | 0.060 | .444** | .916** | 0.071 | .398** | .916** | 0.060 | |

3. Relatedness toward form of activism regarding police brutality | 1 | 0.058 | 0.086 | .952** | 0.077 | 0.126 | .944** | ||

4. Competency toward activism regarding discrimination (perpetrated by civilians) | 1 | .476** | 0.074 | .912** | .480** | 0.054 | |||

5. Autonomy toward activism regarding discrimination (perpetrated by civilians)a | 1 | 0.094 | .432** | .945** | 0.054 | ||||

6. Relatedness toward activism regarding discrimination (perpetrated by civilians) | 1 | 0.092 | 0.119 | .978** | |||||

7. Competency toward activism regarding violence (perpetrated by civilians)b | 1 | .438** | 0.072 | ||||||

8. Autonomy toward activism regarding violence (perpetrated by civilians) | 1 | 0.096 | |||||||

9. Relatedness activism regarding violence (perpetrated by civilians) | 1 |

Table 4 shows the results for the multiple logistic regression that examined the outcome of engagement in activism about police brutality (N = 171) when controlling for gender, race, age, education level, and household income, as well as competency, relatedness, and autonomy. Results show that autonomy toward signing petitions – or knowledge of how to sign petitions – was significantly related to signing the petition. For every one-unit increase in autonomy, the odds of signing a petition increased by 40% (AOR= 1.40, p<.001). We also found that those with higher autonomy scores had a statistically significantly higher odds of sharing on social media regarding police brutality. For every one-unit increase in autonomy, there are 62% higher odds of sharing content regarding police brutality on social media; these findings are statistically significant (AOR= 1.62, p < .001). No statistically significant results were found regarding discussing police brutality with family and friends.

Table 4. Multiple Logistic Regression for Engagement in Activism About Police Brutality (n=171)

| Signing petitions | Sharing on Social Media | Discussing with Friends and Family | |||

Motivators | AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p |

Competency | 1.07 (0.82, 1.28) | 0.463 | 1.00(0.83, 1.22) | 0.964 | 0.74 (.45, 1.21) | 0.231 |

Autonomy | 1.40 (1.18, 1.66) | <.001 | 1.62 (1.34, 1.97) | <.001 | 1.43 (.95, 2.14) | 0.086 |

Relatedness | 1.02 (0.89, 1.18) | 0.738 | 1.03 (.90, 1.19) | 0.666 | 0.96 (.68, 1.35) | 0.806 |

R squared (Nagelkerke) | .225 | .367 | .177 | |||

Note. N = sample size, AOR = adjusted odds ratio, 95% CI = 95% confidence interval Controls for gender, race, age, education level, household income | ||||||

As shown in Table 5, multiple logistic regression was performed to examine engagement and activism about violence against Black Americans (N = 170). We again controlled for gender, race, age, education, household income, and covariates of competency, autonomy, and relatedness towards different types of activism. Results show that both competence (comfort carrying out an action) and autonomy (knowledge of how to carry out an action) are significantly associated with signing petitions. For every one-unit increase in competency, there is 35% higher odds of signing a petition (p < .001); for every one-unit increase in autonomy, there is a 32% higher odds of signing petitions regarding violence against Black Americans (p = .001). We also see 40% higher odds for every one-unit increase in competency that people will discuss violence against Black Americans with their family or friends (p= .004). We find that both competence and autonomy are significantly associated with sharing on social media. For every unit increase in competency, there is 32% higher odds of sharing (p=0.001), and for every one-unit increase of autonomy, there is 45% higher odds of sharing on social media. There are no significant associations between relatedness and any of these outcomes.

Table 5. Multiple Logistic Regression for Engagement in Activism About Violence against Black Americans (n=170)

| Signing petitions | Sharing on Social Media | Discussing with Friends/Family | |||

Motivators | AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p |

Competency | 1.35 (1.14, 1.59) | <.001 | 1.32 (1.20, 1.57) | .001 | 1.40 (1.12, 1.76) | .004 |

Autonomy | 1.32 (1.12, 1.56) | .001 | 1.45 (1.22, 1.73) | <.001 | 0.95 (0.76, 1.19) | .650 |

Relatedness | 1.07 (0.95, 1.22) | .277 | 0.99 (0.87, 1.13) | .898 | 0.93 (0.78, 1.12) | .463 |

R squared (Nagelkerke) | .343 | .377 | .198 | |||

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio, 95% CI = 95% confidence interval, N=170 due to one missing response regarding autonomy. Models control for gender, race, age, education level, household income. | ||||||

As shown in Table 6, multiple logistic regression was run to examine associations between competency, autonomy, and relatedness and activism about discrimination against Black Americans (N = 170). After controlling for gender, race, age, education level, household income, it was found that autonomy (knowledge of how to carry out an action) was the only construct that was significantly related to any type of activism. For every unit increase of autonomy, the odds of signing a petition were increased by 39% (p < .001). For every unit increase of autonomy, the odds of sharing on social media regarding discrimination against Black Americans increased by 23% (p = .011). For every unit increase of autonomy, there were 86% higher odds of discussing discrimination against Black Americans with friends and family (p = .001).

Table 6: Multiple Logistic Regression for Engagement in Activism about Discrimination against Black Americans (n=170)

| Signing petitions | Sharing on Social Media | Discussing with Friends/Family | |||

Motivators | AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p |

Competency | 1.39 (1.17, 1.65) | <.001 | 1.23 (1.05, 1.44) | .015 | 1.86 (1.28, 2.69) | .001 |

Autonomy | 1.15 (0.98, 1.35) | .096 | 1.23 (1.04, 1.46) | .011 | 0.89 (0.64, 1.21) | .448 |

Relatedness | 1.09 (0.97, 1.24) | .147 | 0.98 (0.86, 1.11) | .722 | 0.84 (0.63, 1.10) | .201 |

R squared (Nagelkerke) | .261 | .223 | .364 | |||

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio, 95% CI = 95% confidence interval, N=170 due to one missing response regarding autonomy. Model control for: Gender, race, age, education level, household income | ||||||

We assessed social media sharing as an independent variable with dependent variables of other forms of activism, such as donating money, discussing with other people, protesting, and interjecting when one saw displays of racism. We found that those who shared on social media had 5.09 the odds of donating money to a cause related to Black Lives Matters (p < .001) and 5.04 the odds (p = .007) of discussing any Black Lives Matters topic with friends or family after adjusting for demographics. Results can be seen in Table 7.

Table 7: Logistic Regression of Social Media Shares Predicting Other Forms of Activism (n=171)

| Sharing on Social Media | |||

Outcome Variables | N (%) | AOR (95% CI) | p | R squared |

Donations of funds to programs related to discrimination, violence, or police brutality toward Black Americans | 110 (64.3%) | 5.09 (2.22, 11.69) | <.001 | .134 |

Discussions with others about discrimination, violence, or police brutality toward Black Americans | 156 (91.2%) | 5.04 (1.57, 16.21) | .007 | .152 |

Protesting or attending a rally | 61 (35.7%) | 1.80 (0.75, 4.34) | .327 | .188 |

Interjections on displays of racism | 83 (48.5%) | 2.17 (0.97, 4.87) | .060 | .069 |

Note: Models control for gender, ethnicity, age, education level, and household income.

In this paper, we utilized the Self Determination Theory as our organizing framework to explore the association between motivators for engaging in social media activism and other forms of activism beyond sharing information related to the racism pandemic on social media platforms. Our results suggest that engaging in social media activism is in fact associated with other forms of activism, which is contrary to H1. Our findings also support H2, in that we found that the constructs of autonomy, competency, and relatedness, as outlined by the SDT, are essential to consider when identifying motivations for social media and other forms of activism regarding racist acts in the United States.

When examining SDT and social media activism, autonomy and competency had the largest effect on all outcomes examined: activism against police brutality, and discrimination and violence against Black Americans at the hands of civilians. This indicates that these constructs may be important predisposition factors that impact whether one engages in social media activism, or social activism in general. More simply put, one’s knowledge towards and comfort levels in carrying out a specific action was significantly associated with actually carrying out those actions. The findings regarding autonomy are supported by past research: a meta-analysis of intervention programs designed to increase the autonomy of others found that overall, autonomy-focused interventions are effective (Su & Reeve, 2010). Further, to support participants’ autonomy, researchers found that the intervention must meet the following conditions: 1. provide rationales for intended behavior 2. acknowledge negative feelings 3. use non-controlling language 4. offer options 5. nurture inner motivational resources. These conditions can be adapted and applied to social justice movements, as if individuals feel they know how to engage in a behavior, they may be more likely to do so. Further, applying the SDT lens may be useful in other forms of activism, such as climate change.

Research has also found similar results related to competency and its effect on action. Competency has been a significant motivator for health behavior change (Gillison et al., 2019). Our findings support that increased competency predicts signing petitions, sharing on Social Media, discussing the issues with friends and family, as we see that higher competency is associated with taking action to support anti-violence and anti-discrimination towards Black Americans. Understanding the relationship between one’s competency, or their comfort levels in engaging in an action, and actually carrying out said action is crucial for social justice movements, as many require individuals to protest, sign petitions, or fundraise.

Contrary to our expectations, relatedness was not associated with engaging in social activism for any of the three areas of activism investigated: (1) police brutality, (2) discrimination, or (3) violence against Black Americans. These findings should be considered in light of how relatedness was operationalized in this study, defined as, “How much do you think people in your social circle would care if….” Other operationalizations, such as the social contexts that support the satisfaction of behaviors (Pelletier & Sharp, 2008), may provide additional dimensions to the relatedness construct, and should be further investigated.

The impacts of online social activism are ambiguous, with some researchers saying it can effectively lead to social change and others saying it does not achieve real-world change (Conroy et al., 2012). In our sample, those who shared on social media were more likely to engage in activism in other ways. We also found higher odds of participants who shared social media posts discussing the topics with friends and family t. Lee and Hsieh (2013) found that even those who engage in slacktivism had higher odds of writing to the government. Schumann and Klein (2015) found that those who engage in slacktivism were more likely to engage in signing petitions and attending events regarding a cause but did not participate in more demanding offline activities. This is an important finding from a social activism organization’s perspective and illustrates the value of encouraging people to share posts related to social justice activism, given the higher odds of such behavior leading to other forms of activism in the online sphere.

One study found that individual action is moderated by how strongly a person feels connected to the organization (Kristofferson et al., 2014). This may be useful in communication campaigns, as if organizations are better able to appeal to the public’s emotions about different causes, it may result in increased engagement.

Given the exploratory nature of this study, and the small sample size, we consider this a pilot study of using SDT to conceptualize motivations behind engaging in activism. As we utilized convenience sampling and an internet-based survey, the risk of self-selection bias and self-reported information accuracy must be considered a possible limitation (Dillman et al., 2014; Wright, 2005). Our sample size was predominantly White (44%) and South Asian (30%) and does not capture the US population’s broader racial diversity. Participants were also highly educated, and more than a third of the participants reported annual incomes higher than $100,000. Future studies may consider recruiting from a nationally representative panel to validate the findings. We must also consider the temporal setting of the study. The study was conducted after George Floyd’s murder, which may have heightened attention to racism in the general population. As such, results may be different during a different social context. Further, this study did not collect information regarding the impact of the mode of activism that participants partook in. This data could be important to examine the differential effects between types of activism, for example whether one uses storytelling on social media, versus reposting information, or sharing data about a particular topic.

Social media’s increasing role in contemporary societies is undeniable (Dwivedi, 2018). Much like almost any other aspect of modern life, social media also plays a role in social activism. As stated earlier, social activism is one of the keys to achieving health and social equity through public policy changes across the social determinants of health spectrum. In recent years, social media has been one of the primary vehicles for social activism associated with racial injustices against state-sanctioned violence, such as police brutality (Cammaerts, 2015). Despite heightened awareness of social media’s role in social activism, there remains a critical gap in understanding the underlying mechanisms at the intersection of social media use and social activism (Cammaerts, 2015). This study’s findings can inform social media practices of local and other organizations that work to combat racism and promote social justice.

This study provides insights into the utilization of SDT in explaining motivations towards engaging in sharing information on social media and actions that go beyond that. However, given the limitations of our sample, we recommend more representative research with larger probability samples to further identify the motivation pathways to offer insight into intervention points. This timely study provides some valuable insights into the utility of SDT for social media consumers and social activism beyond just sharing posts on social media. Further research is needed to elucidate the critical SDT pathways. For example, research should investigate existing social media message strategies that may increase autonomy and competency to engage in social activism.

APA. (2020). Racism Pandemic. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2020/05/racism-pandemic

APHA. (2020). Structural racism is a public health crisis: Impact on the black community. American Public Health Association.https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2021/01/13/structural-racism-is-a-public-health-crisis

Alang, S., McAlpine, D., McCreedy, E., & Hardeman, R. (2017). Police Brutality and Black Health: Setting the Agenda for Public Health Scholars. American journal of public health, 107(5), 662–665. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.303691

Bor, J., Venkataramani, A. S., Williams, D. R., & Tsai, A. C. (2018). Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans: a population-based, quasi-experimental study. Lancet (London, England), 392(10144), 302–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31130-9

Boyd R. W. (2018). Police violence and the built harm of structural racism. Lancet (London, England), 392(10144), 258–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31374-6

Census Bureau (2020). Number of people with master’s and doctoral degrees doubles since 2000. The United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/02/number-of-people-with-masters-and-phd-degrees-double-since-2000.html

Cammaerts, B. (2015). Social media and activism. The International Encyclopedia Of Digital Communication And Society, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118767771.wbiedcs083

Cooke, A. N., Fielding, K. S., & Louis, W. R. (2016). Environmentally active people: The role of autonomy, relatedness, competence and self-determined motivation. Environmental Education Research, 22(5), 631–657. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2015.1054262

Deci, E., & Ryan, R. (2020). Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology: Volume 1: Self-Determination Theory.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Deci, E. L., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2004). Self-determination theory and basic need satisfaction: Understanding human development in positive psychology. Ricerche di Psicologia, 27(1), 23–40. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2004-19493-002

Pew Research Center. (2020, November 10). Demographics of internet and home broadband usage in the United States. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/

Pew Research Center. (2020, November 10). Demographics of social media users and adoption in the United States. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/.

Dillman, D., Smyth, J., & Christian, L. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method (4th Edition). Wiley.

Earl, J., Maher, T., & Elliott, T. (2017). Youth, activism, and social movements. Sociology Compass, 11(4), e12465. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12465

Freelon, D., McIlwain, C., & Clark, M. (2018). Quantifying the power and consequences of social media protest. New Media & Society, 20(3), 990-1011. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816676646

Garza, A. (2014). A herstory of the #blacklivesmatter movement. In J. Hobson (Ed.), Are all the women still white? Rethinking race, expanding feminism (pp. 2328). Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Gillet, N., Lafreniere, M. A. K., Huyghebaert, T., & Fouquereau, E. (2015). Autonomous and controlled reasons underlying achievement goals: Implications for the 3× 2 achievement goal model in educational and work settings. Motivation and Emotion, 39(6), 858-875. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-015-9505-y

Gillison, F. B., Rouse, P., Standage, M., Sebire, S. J., & Ryan, R. M. (2019). A meta-analysis of techniques to promote motivation for health behaviour change from a self-determination theory perspective. Health psychology review, 13(1), 110–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2018.1534071

Godlee, F. (2020). Racism: The other Pandemic. BMJ, 369. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2303

Gutsell, J. N., & Inzlicht, M. (2011). Ironic effects of antiprejudice messages: How motivational interventions can reduce (but also increase) prejudice. Psychological Science, 22(12), 1472-1477. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611427918

Jager, J., Putnick, D., & Bornstein, M. (2017). More than just convenient: The scientific merits of homogeneous convenience samples. Monographs Of The Society For Research In Child Development, 82(2), 13-30. https://doi.org/10.1111/mono.12296

Kristofferson, K., White, K., & Peloza, J. (2014). The nature of slacktivism: How the social observability of an initial act of token support affects subsequent prosocial action. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(6), 1149–1166. https://doi.org/10.1086/674137

Laurencin, C. T., & Walker, J. M. (2020). A Pandemic on a Pandemic: Racism and COVID-19 in Blacks. Cell systems, 11(1), 9–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2020.07.002

Legault, L., Gutsell, J. N., & Inzlicht, M. (2011). Ironic effects of antiprejudice messages: How motivational interventions can reduce (but also increase) prejudice. Psychological Science, 22(12), 1472-1477. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611427918

Lee, Y. H., & Hsieh, G. (2013). Does slacktivism hurt activism? The effects of moral balancing and consistency in online activism. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 811-820).

Pelletier, L. G., & Sharp, E. (2008). Persuasive communication and proenvironmental behaviours: How message tailoring and message framing can improve the integration of behaviours through self-determined motivation. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 49(3), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012755

Renström, E., Aspernäs, J., & Bäck, H. (2020). The young protester: the impact of belongingness needs on political engagement. Journal Of Youth Studies, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2020.1768229

Rotman, D. Vieweg, S. Yardi, S. Chi, E. Preece, J. Shneiderman, B. Pirolli, P. and Glaisyer, T. (2011). From slacktivism to activism: participatory culture in the age of social media. Proceedings of the International Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI 2011. Extended Abstracts Volume, Vancouver, BC, Canada. https://doi.org/10.1145/1979742.1979543

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.55.1.68

Segerberg, A., & Bennett, W. L. (2011). Social media and the organization of collective action: Using Twitter to explore the ecologies of two climate change protests. The Communication Review, 14(3), 197-215. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714421.2011.597250

Schumann, S, & Klein, O. (2015). Substitute or stepping stone? assessing the impact of low threshold online collective actions on offline participation. European Journal Of Social Psychology, 45(3), 308-322. https://doi.org10.1002/ejsp.2084

Sheldon, K., Wineland, A., Venhoeven, L., & Osin, E. (2016). Understanding the motivation of environmental activists: A comparison of Self-Determination Theory and Functional Motives Theory. Ecopsychology, 8(4), 228-238. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2016.0017

Smith, M. A., Williamson, L. D., & Bigman, C. A. (2020). Can Social Media News Encourage Activism? The Impact of Discrimination News Frames on College Students’ Activism Intentions. Social Media+ Society, 6(2), https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120921366

Su, Y. L., & Reeve, J. (2011). A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of intervention programs designed to support autonomy. Educational psychology review, 23(1), 159-188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9142-7

Wright, K. (2006). Researching internet-based populations: advantages and disadvantages of online survey research, online questionnaire authoring software packages, and web survey services. Journal Of Computer-Mediated Communication, 10(3), 00-00. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2005.tb00259.x

The authors would like to thank Karen Mackey for her support with research logistics. This study received funding from the Department of Behavioral and Community Health at the University of Maryland, School of Public Health

The author(s) have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Munjireen Sifat is completing her PhD in the Behavioral and Community Health Department at The University of Maryland. Her research areas include mental health and digital health. She is joining the University of Oklahoma at the Health Promotion Research Center as a post-doctoral researcher.

Shawn Chiang, MPH is a Doctoral Academy Fellow in the Department of Health, Human Performance, and Recreation at the University of Arkansas. His research focuses on health communication and computational social science in the area of cancer prevention.

Nazra Amin is completing her MPH in Global Health Epidemiology and Disease Control at The George Washington University. Her research areas include decolonizing global health, global mental health, and sexual and reproductive health.

Samira Traore is completing her MPH in Humanitarian Health at the George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health. She is interested in studying health disparities at the global level, and within the context of complex emergencies.

Ans Irfan is a multidisciplinary global public health scholar and practitioner. His work focuses on translating evidence into policies and programs to ameliorate social, racial, and health inequities.

Dr. Kerry Green is an associate professor in the Behavioral and Community Health Department at The University of Maryland. As a prevention scientist, Dr. Kerry Green’s work concentrates on improving the health and well-being of disadvantaged populations. Her research focuses on identifying the causes of adverse outcomes over the life course among urban African Americans, including structural factors.

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()