Rea S, Coleman A, Omonuwa K, Weldense S. Improving spoken language interpreter services for birthing people. HPHR. 2021;52. 10.54111/0001/ZZ2

Health disparities for perinatal people in North Carolina (NC) with limited English proficiency (LEP) are widening, including decreased access to quality prenatal care, higher-risk deliveries, disproportionate obstetric trauma, and increased postpartum depression. Several obstacles exist related to utilization and availability of medical interpreters, and without swift policy action to address these barriers to linguistically accessible care, health disparities will continue to widen. The aim of this commentary is to assist NC in developing policy that increases health equity for perinatal people with LEP. Through utilization of a socioecologic framework and SWOT analysis, we proposed four different policies related to medical interpreter services. Proposed policies were: 1) to improve the quality of training for medical interpreters by requiring that all interpreters be board certified, 2) to provide Medicaid reimbursement to hospitals and providers for interpreter services, 3) to mandate culturally-sensitive curricula in medical schools, and 4) to allocate funding for language concordant statewide perinatal education that includes information about navigating healthcare systems with LEP, patients’ rights, and patient advocacy. Current policies are insufficient to address the widening health disparities that are occurring for perinatal people with LEP. The proposed policies are worthy of consideration for implementation to further address reducing health disparities for birthing people with LEP at patient, provider, and structural levels.

Patients in the United States (U.S.) who have limited English proficiency (LEP) are defined as individuals who do not speak English as their first language, and have a limited ability to read, write, speak, or understand English (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013). The number of patients with LEP in the U.S. is continuing to grow (Yeheskel & Rawal, 2019). Eleven percent of families in North Carolina (NC) speak a language other than English at home, and there are 437,382 North Carolinians who are LEP (Tippett, 2016; U.S. Census Bureau, 2015).

In the U.S. Medicaid population, LEP is concentrated among Hispanic, Asian, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, American Indian and Alaskan native populations, as well as those with lower educational attainment (CMS, n.d.). Language barriers in healthcare for historically oppressed populations widens health disparities compared to native English speakers. Although medical interpreters exist through in-person, telephone, and virtual platforms, they are often underutilized or undertrained, further contributing to inequitable care and outcomes (Karliner et al., 2007).

Health disparities associated with language barriers exist in the perinatal period, which includes pregnancy, labor and delivery, and postpartum care. The words women, maternal, maternity care, and mothers are used throughout this paper, although we recognize the value of gender-neutral terms such as perinatal health and birthing people. Patients with LEP have experienced double the risk of obstetric trauma during vaginal births, higher-risk deliveries, greater complications after emergency cesarean surgeries, and increased postpartum depression (Hines et al., 2014; Jacoby et al., 2015; Sentell et al., 2016; St Fleur & Petrova, 2014). Furthermore, birthing people with LEP have demonstrated limited breastfeeding knowledge and reduced opportunities for breastfeeding education compared to English speaking birthing people (St Fleur & Petrova, 2014). During the COVID-19 pandemic, in-person interpreters were considered non-essential staff, which further exacerbated health disparities for birthing people with LEP (Le Neveu et al., 2020). These disparities stem from language barriers that prevent fully informed consent, patient education, and confidentiality breaches from using ad hoc interpreters such as family members, friends, or other providers who are not on the patient’s care team.

Disparities among non-native English speakers are reflective of historical racial and ethnic oppression in the U.S.. As the population of people with LEP continues to grow rapidly, health disparities will widen if no policy action is taken. This paper aims to 1) discuss contributing factors to health disparities for birthing patients with LEP, 2) describe gaps in existing policies and programs, and 3) propose four policies that could benefit birthing people in NC with LEP. Policy makers should prioritize reducing health disparities for perinatal patients with LEP in NC to improve health outcomes in an equitable and cost-effective manner.

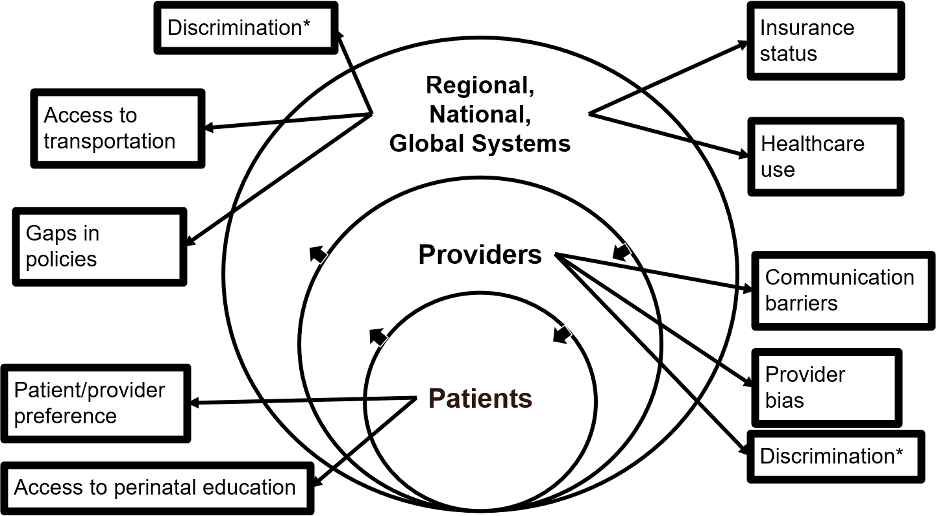

Factors contributing to increased health disparities for birthing people with LEP are shown in an adapted socioecological framework (Figure 1). At the individual level, perinatal patients have reported preferences for using various interpreter platforms, including in-person, telephone, or bilingual physicians, with many participants preferring in-person interpreters (Joseph et al., 2018; Pathak et al., 2021). One study reported that by providing patients with LEP access to a preferred interpreter service, informed consent processes were improved (Lee et al., 2017). Immigrant birthing people in particular may lack support networks, access to perinatal education, and familiarity with navigating healthcare systems (Trainor et al., 2020). There have also been documented disparities related to health literacy, educational status, and socioeconomic status (Prasannan et al., 2021).

Figure 1. Adapted Socioecological Framework

Interpersonal contributions to health disparities for birthing people with LEP are prominent within healthcare teams. One review identified several themes that contribute to overall patient experience for patients with LEP, including communication barriers, relationships with health care providers, discrimination and identity, and cultural safety (Yeheskel & Rawal, 2019). Inclusion of professional in-person interpreters as part of the care team allows translation of verbal and nonverbal patient expressions, yet health care providers often attempt to communicate with their own limited language skills or nonverbally (Betancourt et al., 2012; Le Neveu et al., 2020). Provider bias occurs when providers make assumptions about a patient’s primary language, or when discrimination prohibits shared-decision making in maternity care (Betancourt et al., 2012; Cheng et al., 2020).

Living and working conditions also contribute to worse health outcomes for birthing people with LEP. A higher percentage of immigrant women are giving birth in comparison to U.S. born women (Pew Research Center, 2020). NC Medicaid covers approximately 50% of pregnancies and deliveries in the state, yet pregnant undocumented immigrants in NC often do not qualify for Medicaid and must obtain care at Federally Qualified Health Centers (Daw et al., 2020; NCDHHS, 2020). The next sections will discuss policies and structural factors that exist within the healthcare system that aim to address quality of care for birthing people with LEP.

Through both section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the 1964 Civil Rights Act, all health care providers who receive federal funds are required to develop systems to improve access to their services for individuals with LEP. Whether or not meaningful access has been provided is made on a case-by-case basis, and can also vary depending on factors such as the proportion of individuals with LEP who are likely to be served and the cost of language assistance services (Department of Health and Human Services, 2016; Federal Coordination and Compliance Section Civil Rights Division U.S. Department of Justice, 2011; Jacobs et al., 2018).

Furthermore, states are not required to reimburse providers for the cost of language services, nor are they required to claim related costs to Medicaid/CHIP. The cost of medical interpreters ranges from $75-150 an hour, which serves as a barrier to services in small practices and hospitals (Department of Health and Human Services, 2016; Jacobs et al., 2018). However, medical interpreters are cost-effective when considering health outcomes and disparities associated with lack of interpretation (Brandl, 2020). Furthermore, there are time constraints involved with using an interpreter, which health care providers are often not compensated for (Diamond et al., 2009).

As of 2016, patients with LEP have the right to sue healthcare providers for language access violations via Section 1557 of the ACA (Lingolet, n.d.). Additionally, the Minority Health’s Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services standards and the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) require interpreter services for patients with LEP with limited delay (Mejia, 2019). Further existing policies and programs are discussed within the following sections.

We used an adapted socioecological framework (Figure 1) and SWOT analysis of NC hospitals (Table 1) to gain background information on existing disparities and policy gaps. We then selected four proposed policies for consideration, which are elaborated upon in the following sections.

Table 1. SWOT Analysis

Strengths What do NC hospitals do well? Some hospitals have a broad range of resources to interpreter services

What resources do NC Hospitals have?

| Opportunities What trends support the NC hospitals’ focus on disparities?

What existing relationships can the practice leverage?

Not always up to date, but could be improved through patient intake/registration

|

Weaknesses What do NC hospitals do poorly? · Connecting patients w/ language access services, notifying providers of a patient’s LEP · Ad hoc interpreters used (family, friends, providers who are not trained) (Ali and Watson 2018; Gerchow et al. 2021) · Underutilization of federal funding for interpreter services (KFF, 2021; NHeLP, 2010) · Incomplete documentation of patients’ primary languages or when interpreter service are utilized · Limited provider knowledge of interpreter services and cultural humility o Limited education in health professional schools on culturally concordant care and cultural humility · Lack of accountability for improper usage of interpreter services What is missing from NC Hospitals? · Requirements for medical interpreter certification · Variability and inconsistency between hospitals and birthing facilities · No Medicaid reimbursement for use of interpreter services in North Carolina · Inconsistent perinatal education across the state and possibly within the same facility | Threats What new policies affect NC hospital operations? · Section 1557 of the ACA · Inconsistency with reimbursement o Room for interpretation of laws and no clear definition of what proper access/use of interpreter services look like What community priorities may conflict with plans for equity? · Not wanting to seek care due to past negative experiences related to LEP o Not wanting to face discrimination due to LEP o Wanting to receive language concordant care · Patients with LEP who are uninsured may seek care at federally qualified health centers, which may have different reimbursement models |

What is unknown? What new information do you need? · Solicit input from legislators, hospital systems, patients who use interpreter services · Total number of in-person interpreters, how many interpreters would be needed to bridge the gap o Is there a shortage or a surplus? o What is the required training and accreditation? Barriers to training? · Discussing the burdens, concerns, and challenges for interpreters | |

The use of professional medical interpreters has been associated with reduced disparities, improved clinical outcomes, and improved patient satisfaction (Jimenez et al. 2012; Karliner et al. 2007). There are two national accrediting bodies for medical interpretation in the U.S. The Certification Commission for Healthcare Interpreters (CCHI) and The National Board for Certification of Medical Interpreters (NBCMI) both provide written and oral board examinations to certify medical interpreters. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are over 11,000 medical interpreters currently working in the U.S. (2019). However, only an estimated 6,000 of these interpreters are certified through CCHI or NBCMI (Certification Commission for Healthcare Interpreters, n.d.; The National Board of Certification for Medical Interpreters, 2016).

The distinction between fluency in a language and competency in interpretation is important to note. Although individuals must report fluency to apply for board certification, the federal exam passing rates for national interpreter exams ranges from 4-13%, highlighting the unique skills that medical interpreters must acquire (VanderWielen et al., 2014). Furthermore, studies of interpreters demonstrate increased medical errors in populations with LEP when an ad hoc interpreter is used compared to a professionally trained medical interpreter (Flores et al., 2012). A recent systematic review found that ad hoc interpreters are still often used, including physicians, nurses, family members, and friends who have not been trained in medical interpretation (Ali and Watson, 2018; Gerchow et al., 2021).

This proposed policy would aim to improve accreditation standards for medical interpreters in NC by requiring that all medical interpreters are board certified. North Carolina does not require that medical interpreters be certified through NBCMI or CCHI, which creates a gap in the quality of medical interpreters being used clinically. There are significant differences in the training of a certified interpreter and someone who may be qualified, and without regulating these differences, birthing people with LEP are experiencing greater numbers of medical errors and reduced quality of care. California, New York, New Jersey, North Dakota, and Vermont implemented similar policies requiring all medical interpreters to be board certified through NBCMI or CCHI (California Code of Regulations, 2013; Youdelman, 2019). North Carolina should require all medical interpreters to undergo board certification and licensing through NBCMI or CCHI, which could contribute to fewer medical errors, improved health outcomes, greater patient satisfaction, and reduced health disparities.

Currently, NC Medicaid covers more than 55% of deliveries in the state (NCDHHS, 2020). Marginalized populations, such as those with LEP, are overrepresented in the Medicaid population (NCDHHS, 2020). Although undocumented immigrants in NC do not qualify for full Medicaid for Pregnant Women (MPW), the Emergency Medicaid program covers birthing costs (Tucker & Zachary, 2020). More than 80% of Emergency Medicaid claims are obstetric related, and almost 100% of the users are undocumented immigrants (Swartz et al., 2017).

North Carolina must ensure that patients with LEP are receiving adequate language services in order to maintain compliance with federal legislation. Furthermore, approximately 1 in 40 malpractice claims are a result of failure to provide interpretation services, and settlements can cost millions of dollars (Jacobs et al., 2018). NC Medicaid does not currently reimburse providers for interpreter services (Mejia, 2019). However, the federal government is able to assist states and health care providers with the costs of language services through covered services, administrative costs, and disproportionate share hospitals (DSH) (NHeLP, 2010).

As the number of individuals living with LEP continues to grow, NC will need to rethink their current policies to ensure compliance with federal legislation and strive towards equitable birthing outcomes for all. Medicaid reimbursement for interpreter services has the potential to improve medical outcomes for birthing people with LEP and decrease health care costs associated with medical errors.

This proposed policy is intended to increase access to interpreter services by ensuring proper funding for providers and health care facilities who use them. North Carolina would not be the first state to provide Medicaid coverage for interpreter services, as 14 states (Hawaii, Iowa, Idaho, Kansas, Maine, Minnesota, Montana, New Hampshire, New York, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and Wyoming) and the District of Columbia are currently providing Medicaid reimbursement for interpreter services (Jacobs et al., 2018). Looking to states with established programs can guide NC as it establishes its own program, as well as help the state anticipate costs. Although the Federal government is paying a large portion of the additional costs, this policy would increase the immediate costs to NC Medicaid. However, Medicaid reimbursement for interpreter services has great potential for cost savings due to improved quality of care for populations with LEP.

Despite living in a linguistically diverse nation, language proficiency and skills to address cultural aspects of clinical care, research, and education are severely lacking in health professional training (Molina & Kasper, 2019). While the number of patients with LEP is growing, many medical schools fail to offer medical language courses, which disincentivizes language-concordant and culturally competent care (Pereira et al., 2020). Incorporating historical events which lead to stereotyping and bias in medicine are crucial to understanding deep rooted mistrust in the U.S. healthcare system by persons of color and those who have LEP.

Cultural humility in the medical context is the process of being aware of how people’s culture can impact their health behaviours and in turn using this awareness to cultivate sensitive approaches in treating patients (Prasad et al., 2016). Unlike cultural competency, cultural humility has no end point and does not require demonstration of a ‘quantifiable set of attitudes’. This concept is a continual process, one that requires self-reflection and self-critique (Prasad et al., 2016).

This proposed policy would mandate that all medical schools in NC integrate education about interpreter services into existing cultural competency and cultural humility curricula. Using the skeleton of the cultural competency curriculum and The Tool for Assessing Cultural Competence Training (TACCT), schools will be able to implement cultural humility curricula. Implementing a culturally competent/humility curriculum requires institutional support and commitment, dedicated community leaders, and a clearly defined accountability and evaluation process (AAMC, 2005). Moving forward, institutions should aim to create more diversity in the students and residents that they recruit, in order to create a workforce that is reflective of the languages spoken in the U.S. (AAMC, n.d.).

Thus, the proposed cultural curriculum would be intended to teach culture-concordant care which could also encompass content areas such as relevant health inequities that commonly affect patients who speak different languages, cultural sensitivity, humility, and bias, particularly around beliefs and practices that affect health and wellbeing, and how to work in language-discordant encounters with interpreters and other modalities (Molina & Kasper, 2019). This professionalization of language competency in medical schools can “improve patients’ trust in individual physicians and the profession as a whole; improve patient safety and health outcomes; and advance health equity for those we care for and collaborate with in the U.S. and around the world” (Molina & Kasper, 2019).

The goal of formal childbirth education is to provide birthing people with up-to-date knowledge about labor and birth, how to manage labor-related challenges, make informed decisions about their care, and strategies for how to advocate for themselves in the healthcare system (Lothian, 2016). Perinatal education positively impacts pregnancy, childbirth, breastfeeding, and the transition to parenthood (Zolotor & Carlough, 2014). For perinatal education to be accessible to individuals with LEP, it must implement aspects of culturally humble care which can increase patient satisfaction, adherence to treatment, and engagement with providers (Brunett & Shingles, 2018). Common components of culturally appropriate care include incorporating culturally specific concepts, using culturally and/or linguistically appropriate materials, involving the family, offering telemedicine, and increasing outreach (Handtke et al., 2019).

Multiple examples of culturally responsive perinatal education have emerged over the last decade. One study evaluating the effectiveness of a multi-prong breastfeeding intervention delivered in Chinese to Chinese American birthing people discovered that both any and exclusive breastfeeding increased by 16.8% and 9.1% respectively (Lau et al., 2021). DeStephano et al. found that using culturally tailored educational videos in the clinic setting decreased cultural barriers to care and increased health knowledge among pregnant Somali birthing people (DeStephano et al., 2010). Another study of pregnant Hispanic women noted that issues related to prenatal care included language barriers, the attitudes of providers, and inadequate access to information about pregnancy yet also suggested that group education classes could address those concerns (Fitzgerald et al., 2016).

The CenteringPregnancy program uses a group discussion format and incorporates 3 different components of prenatal care: risk assessment, education, and support (Rising, 1998). Over 200 provider settings across the U.S. and Canada have adapted the CenteringPregnancy model to different populations (Walker & Worrell, 2008). One example of modifying the CenteringPregnancy model for Japanese birthing people to better suit the needs and preferences of the population meant developing transcultural modifications such as education about navigating healthcare systems with limited English skills, advice about travel precautions, and technical knowledge about breastfeeding (Little & Fetters, 2019). Another study comparing CenteringPregnancy to individual prenatal care in Latina Spanish-speaking birthing people found that individuals who participated in CenteringPregnancy had higher odds of attending prenatal and postpartum care visits (Trudnak et al., 2013), while another study investigating the effectiveness of CenteringPregnancy in Spanish speaking birthing people found improved birth outcomes (Tandon et al., 2012). In all of the previous CenteringPregnancy examples, the program was delivered in the primary language of the participants, highlighting the need for linguistically accessible education, especially since group education provides participants with additional opportunities to create support networks (Little & Fetters, 2019).

This proposed policy entails allocating funding for the implementation of a state-wide perinatal education program in major hospital systems using the CenteringPregnancy model. The CenteringPregnancy model is currently available in at least 19 medical practices in NC and consistently leads to improved birth outcomes (Strickland et al., 2016). An initial pilot of the program will be delivered in NC’s most commonly spoken languages, English and Spanish with plans to increase the scope over 5 years (Tippett, 2016). To ensure that the model is appropriate for birthing people with LEP, the curriculum will undergo transcultural adaptations and include topics such as navigating healthcare systems with LEP, information about patients’ rights, and tips for patient advocacy, and newborn baby education (Congden, 2016; Little & Fetters, 2019). Additionally, materials will be available online and through local health departments to increase the accessibility of resources for patients with LEP, especially with the onset of COVID-19 showing the benefit of online and smart-phone based education programs (Olivia Kim et al., 2019; Pasadino et al., 2020). Finally, to monitor the impact of the program and inform future adaptations, each site will conduct an annual evaluation of the model and include concepts such as parenting knowledge, parenting experience, and program satisfaction (Benzies et al., 2016).

Several policy options exist to reduce health disparities for perinatal people with LEP in NC. We identified four potential policies that could be useful for prenatal, birthing, or postpartum folks with LEP. Current policies are insufficient to address the widening health disparities that are occurring during prenatal care, labor and delivery, and postpartum care due to language barriers between patients and providers. Although this analysis focuses on perinatal people with LEP in NC, implementation of any of these policies is likely to benefit a broader population. However, by targeting a policy toward a vulnerable group with disproportionately worse health outcomes, it would be expected that health disparities between birthing people with LEP and English-speaking birthing people would be reduced.

We would like to thank Dr. Cleo Samuel-Ryals for her support and passion for reducing health disparities, and for her outstanding dedication to teaching.

The author(s) have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

AAMC. (2005). Cultural Competence Education. Retrieved May 4, 2021, from

https://www.aamc.org/media/20856/download

AAMC. (n.d.). GSA Committee on Student Diversity Affairs

(COSDA). Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.aamc.org/professional-development/affinity-groups/gsa/cosda

DeStephano, C. C., Flynn, P. M., & Brost, B. C. (2010). Somali prenatal education video use in a United States obstetric clinic: a formative evaluation of acceptability. Patient Education and Counseling, 81(1), 137–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.12.003

Diamond, L. C., Schenker, Y., Curry, L., Bradley, E. H., & Fernandez, A. (2009). Getting by: underuse of interpreters by resident physicians. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 24(2), 256–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0875-7

Fitzgerald, E. M., Cronin, S. N., & Boccella, S. H. (2016). Anguish, yearning, and identity: toward a better understanding of the pregnant hispanic woman’s prenatal care experience. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 27(5), 464–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659615578718

Gareau, S., Lòpez-De Fede, A., Loudermilk, B. L., Cummings, T. H., Hardin, J. W., Picklesimer, A. H., Crouch, E., & Covington-Kolb, S. (2016). Group Prenatal Care Results in Medicaid Savings with Better Outcomes: A Propensity Score Analysis of CenteringPregnancy Participation in South Carolina. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20(7), 1384–1393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-1935-y

Lau, J. D., Zhu, Y., & Vora, S. (2021). An evaluation of a perinatal education and support program to increase breastfeeding in a chinese american community. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 25(2), 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-020-03016-z

Lothian, J. (2016). Does childbirth education make a difference? The Journal of Perinatal Education, 25(3), 139–141. https://doi.org/10.1891/1058-1243.25.3.139

Mejia, C. (2019). The echo in the room: barriers to health care for immigrants and refugees in north carolina and interpreter solutions. North Carolina Medical Journal, 80(2), 104–106. https://doi.org/10.18043/ncm.80.2.104

Molina, R. L., & Kasper, J. (2019). The power of language-concordant care: A call to action for medical schools. BMC Medical Education, 19(1), 378. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1807-4

Pasadino, F., DeMarco, K., & Lampert, E. (2020). Connecting with Families through Virtual Perinatal Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic. MCN. The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 45(6), 364–370. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMC.0000000000000665

Pathak, S., Gregorich, S. E., Diamond, L. C., Mutha, S., Seto, E., Livaudais-Toman, J., & Karliner, L. (2021). Patient Perspectives on the Quality of Professional Interpretation: Results from LASI Study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06491-w

Pereira, J. A., Hannibal, K., Stecker, J., Kasper, J., Katz, J. N., & Molina, R. L. (2020). Professional language use by alumni of the Harvard Medical School Medical Language Program. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 407. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02323-x

Pew Research Center. (2020). Key findings about U.S. immigrants. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/20/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/

Trudnak, T. E., Arboleda, E., Kirby, R. S., & Perrin, K. (2013). Outcomes of Latina women in CenteringPregnancy group prenatal care compared with individual prenatal care. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 58(4), 396–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.12000

Tucker, W., & Zachary, C. (2020). Medicaid coverage for pregnant women: A pathway to healthy outcomes for moms and children. North Carolina Medical Journal, 81(1), 51–54. https://doi.org/10.18043/ncm.81.1.51

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2013, July 26). Guidance to Federal Financial Assistance Recipients Regarding Title VI and the Prohibition Against National Origin Discrimination Affecting Limited English Proficient Persons – Summary. Retrieved April 19, 2021, from https://www.hhs.gov/civil-rights/for-providers/laws-regulations-guidance/guidance-federal-financial-assistance-title-vi/index.html

VanderWielen, L. M., Enurah, A. S., Rho, H. Y., Nagarkatti-Gude, D. R., Michelsen-King, P., Crossman, S. H., & Vanderbilt, A. A. (2014). Medical interpreters: improvements to address access, equity, and quality of care for limited-English-proficient patients. Academic Medicine, 89(10), 1324–1327. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000296

Vela, M., Fritz, C., & Jacobs, E. A. (2016). Establishing Medical Students’ Cultural and Linguistic Competence for the Care of Spanish-Speaking Limited English Proficient Patients. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 3(3), 484–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-015-0165-0

Youdelman, M. (2019). Summary of State Law Requirements Addressing Language Needs in Health Care – National Health Law Program. National Health Law Program. https://healthlaw.org/resource/summary-of-state-law-requirements-addressing-language-needs-in-health-care-2/

Ms. Samantha Rea is a MD student at the Wayne State University School of Medicine. She completed her MPH at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She is pursuing a residency in pediatrics and pediatric physical medicine and rehabilitation. Her interests include health policy, social determinants of health, and adolescent sexual and reproductive health.

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()