Sugar S, Coyle T. Keep your pin up: students combating opioid use disorder stigma with lapel pins. HPHR. 2022;50. 10.54111/0001/WW1

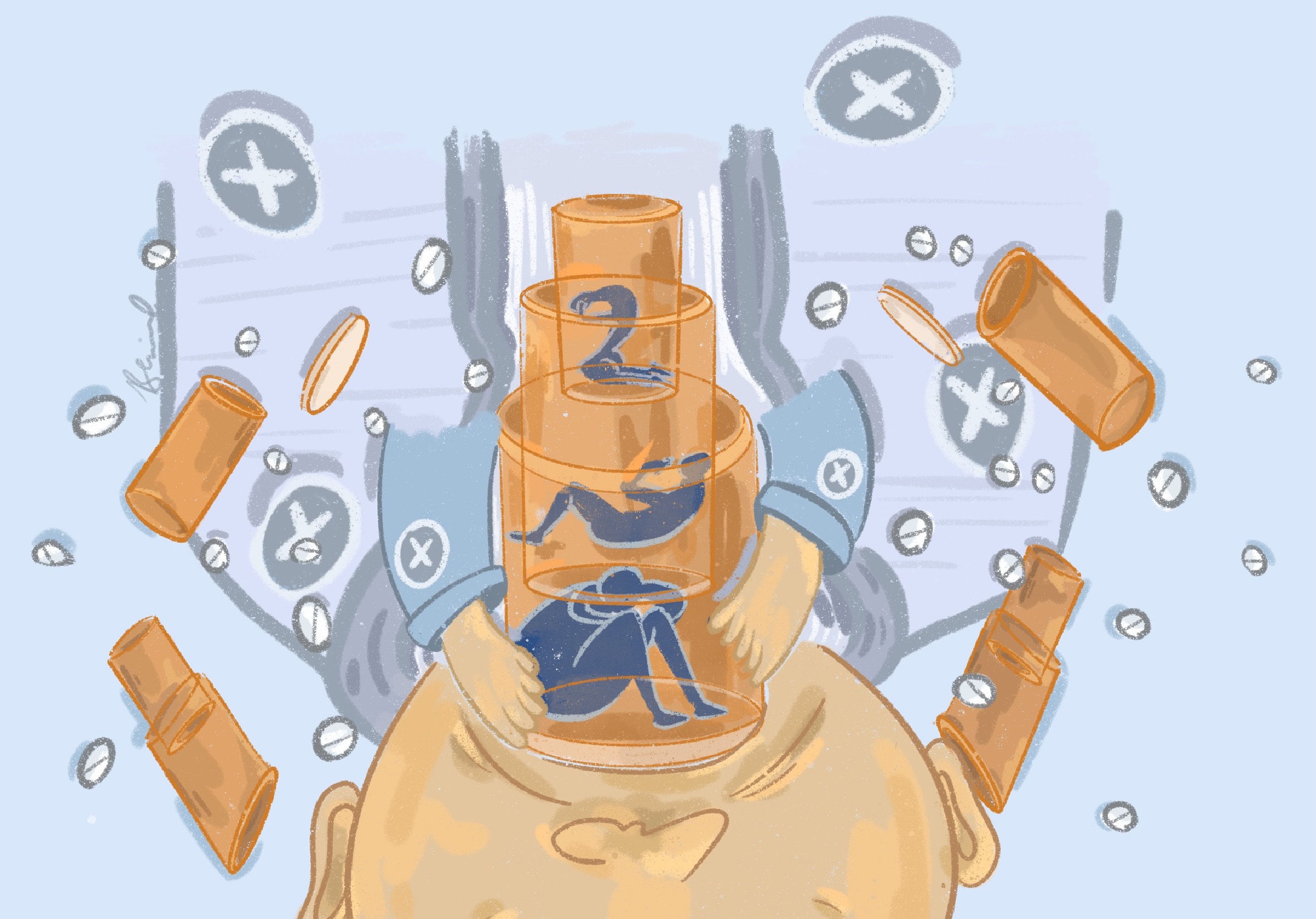

Drug overdose death rates continue to rise – more Americans and Coloradans are dying of drug overdoses than ever before. Despite efforts to shift the narrative, our society continues to struggle to acknowledge substance use disorders as medical conditions worthy of medical care. Rural settings are no exception. In this piece, a University of Colorado medical student describes her experience working to fight stigma surrounding opioid use disorder in both lay and healthcare professional populations. By designing and employing the use of lapel pins, students are leading a grassroots campaign to combat opioid use disorder stigma among healthcare professionals at the outset of their careers. Using real experiences from a rural clinic, the authors explore barriers to addiction care, including how stigma can perpetuate sub-optimal care for treatable medical conditions.

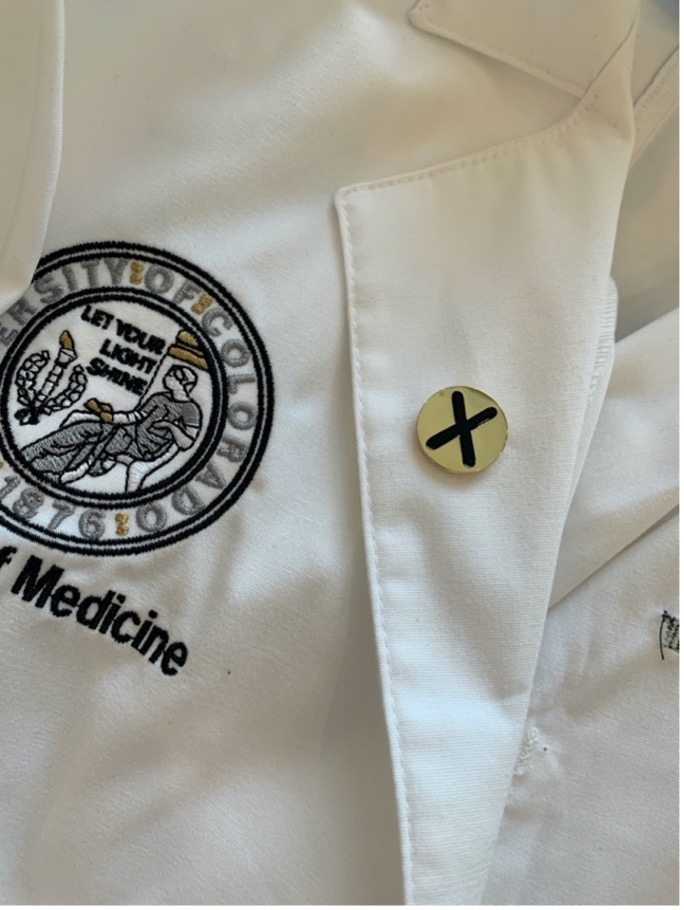

Photograph 1. “X” lapel pin

The lapel pin was designed with an X, a nod to the X Waiver, signifying the completion of federally approved buprenorphine waiver training and displays the wearer’s interest in talking openly about and treating OUD.

“We don’t treat those kinds of people here. I don’t even let them in the waiting room anymore.” Nestled between introductions and morning pleasantries, these are the words my attending shared in my first few minutes with him. I was just beginning a new medical school clerkship in his rural clinic. He was speaking about those in his community with opioid use disorder (OUD).

I had twenty ‘first days’ throughout my third year of medical school. Twenty different clinical sites and teams for rotations. Twenty first impressions. Twenty orientation tours. This time, I was placed in rural Colorado. I will never forget it. Upon meeting my attending, he introduced himself and quickly asked, “What’s up with the X?”

I reflexively looked down at my white coat. I was surprised – nobody had noticed my lapel pin that quickly before. I explained the meaning of the shiny golden “X” pinned to my coat. The “X Waiver” authorizes medical providers to prescribe buprenorphine, one of three FDA-approved medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD). My mentor and I designed the white coat lapel pins with an “X” on them as a nod to the waiver for those who completed the training required to use buprenorphine; to signify my interest in talking openly about and treating substance use and combating stigma.

“Oh, I thought about getting my X Waiver… but never did. Those people make bad choices in life, then disrupt my office full of patients.” I doubt my face hid my dismay. Perhaps his attitude reflected the values of his upbringing, or perhaps years of practice had hardened him from the emotional demands of caring for patients. Then again, maybe he was just the product of a medical education system which so often failed to provide clinicians with a foundation or training in addiction medicine. Regardless, I mustered a placating response, fixed my face, and carried on with first-day orientation as best as I could. Despite his disappointing reaction, though, I knew this was why we created the pins.

Drug overdose death rates continue to soar. Over 100,000 fatal drug overdoses were reported in the United States in the 12 months ending in May 2021, the highest annual number ever.1 Despite efforts attempting to shift the narrative, our society struggles to acknowledge substance use disorders as medical conditions worthy of medical care – especially in rural settings.

In Colorado, 1 in 10 residents live in places with no access to substance use treatment, with many in remote rural areas having to travel over 30 miles to seek treatment.2 Roughly 13% of Coloradans live in rural or frontier areas of the state, many of which have been heavily affected by drug use.4 Colorado’s rural areas experienced a 140% increase in drug overdose deaths from 2002-2014, while urban areas experienced 96% increase in overdose deaths during that same time frame.5

In 2020, 1,477 Coloradans died of drug overdoses – the most overdose deaths ever recorded in the state, and a sharp increase from 2019. Fentanyl overdoses more than doubled between 2019 and 2020, and have increased ten-fold since 2016.6 Access to care is limited: only about a quarter of the 47,000 Coloradans with OUD receive medical treatment. During 2016-2017, almost half (46%) of the 702 providers in Colorado holding a federal waiver did not prescribe buprenorphine, and only 8% of providers able to prescribe buprenorphine for OUD were in rural counties.7 This provider distribution embodies the reality that many patients with OUD experience stigma when seeking healthcare in rural settings. Unfortunately, legislation has not been advanced to subsidize transportation costs for patients, or properly expand the use of telemedicine or pharmacy-dispensed treatment. Stigma with roots in both individual attitudes of providers, as well as the enactment of public policies limiting harm reduction resources in rural communities, drives (in)access to substance use care.8,9

The University of Colorado’s Interprofessional Clinical Opioid Use Disorder (ICLOUD) curriculum aims to improve addiction care through provider education. This project was awarded a grant from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to train medical, nurse practitioner, and physician assistant students to provide buprenorphine products to treat patients with OUD. To date the program has held 9 federally approved trainings, with over 350 healthcare professions students attending the trainings.

In a student-led grassroots anti-stigma campaign in partnership with ICLOUD, a classmate and I co-founded the Interprofessional Addiction Medicine Student Interest Group (IAMSIG) in 2020. We hoped to educate our healthcare peers regarding the value of MOUD, and to view OUD as a medical condition worthy of evidence-based treatment. In its inaugural year, IAMSIG held a virtual Narcan training and coordinated a careers in addiction medicine panel with local experts. We have since organized field trips to Arapahoe County Recovery Court and Denver’s Harm Reduction Action Center, hosted book clubs, and helped establish a second chapter at Rocky Vista University College of Osteopathic of Medicine in nearby Parker, CO.

We launched our lapel pin project to combat OUD stigma among healthcare professionals at the outset of their careers. We designed the “X” pins in black and gold (CU’s school colors) and have distributed over 300 pins to students and faculty since 2020. We hope the pin will encourage providers to advocate for evidence-based substance use disorder treatment within our healthcare system without stigmatizing patients who need care. Coupling the buprenorphine training with a lapel pin creates an opportunity for a conversation about OUD treatment, helping facilitate education and translate beliefs into actions.

My attending proved to me that we needed these pins. I wore mine with pride, despite his reaction. During my second week of the rotation, I had a clinic visit with an older woman seeking care for her diabetes. During this encounter, my patient asked, “What is that X on your coat?” A flash of déjà vu passed, and I told her the same explanation about treating OUD, advocacy, and fighting stigma I had offered to my attending.

Instead of dismissing me, her eyes lit up. She explained that her friends were dealing with chronic pain and had recently moved from using prescription opioids to now getting drugs “from the streets,” which worried her. She said her friends have talked about taking their own lives to escape their addictions, and that their doctors have turned their backs on them. She said she would talk about MOUD with her friends, and that our conversation restored some of her faith in the healthcare system. She said our conversation made her day; it certainly made mine.

These dichotomous interactions reaffirmed my commitment to fighting stigma in substance use care. I won’t win everyone over – I found that out quickly enough. But maybe I’ll move the needle just enough to make a difference for a patient, loved one, or colleague struggling with substance use in the future. That’s all I can hope for.

The authors have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Funding for this work was made possible in part by grant no. 1H79TI082556 from SAMHSA. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Additionally, this work was supported by the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Sophia Sugar is a medical student at the University of Colorado School of Medicine (CUSOM). After earning her Bachelor of Science from Gettysburg College, she performed research at Nationwide Children’s Hospital Center for Perinatal Research in Columbus, Ohio. There, Sugar investigated the effects of perinatal inflammation on neonatal lung development. She is currently an MD candidate in the CUSOM Class of 2023, where she has a particular interest in addiction medicine.

David (Tyler) Coyle is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. He is board-certified in both Preventive and Addiction Medicine, and serves as Assistant Medical Director for CU’s Addiction Research & Treatment Services Adult Outpatient Program. He specializes in the management of opioid use disorder. After earning his medical degree from Columbia University, Dr. Coyle completed his residency training in Public Health & General Preventive Medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, where he also earned a master’s degree in Epidemiology. Following residency, Dr. Coyle worked at the U.S. Food & Drug Administration as a medical pharmacoepidemiologist specializing in the non-medical use of drugs. He serves as the Program Director for CU’s Public Health & General Preventive Medicine Residency.

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()