Melchiorre M, Merhavy Z. Treating Hepatitis C in medicine and primary care through a telehealth model; a curriculum. HPHR. 2022;50. 10.54111/0001/WW2

The American Association for the Study of Liver Disease created a simplified cascade for the treatment of non-cirrhotic, treatment naïve, adults with hepatitis C. Given the expanded guidelines, a novel curriculum was implemented to train nonspecialist providers. With the need for immediate access to hepatitis C treatment, in part due to the increase in IV drug use creating a new cohort of those infected, this project assessed the efficacy of a curriculum designed to train nonspecialist providers to treat hepatitis C following CDC and AASLD simplified guidelines.

The educational curriculum and survey setting was an addiction medicine telehealth-based practice operating in several states including New Jersey, Michigan, Texas, Ohio, California, Alaska, and Florida. The providers included physician assistants and nurse practitioners who ranged from newly graduated to over twenty years’ experience. The survey had 23 questions assessing points on treating hepatitis C, past experiences, comfort level and feelings about the curriculum and support.

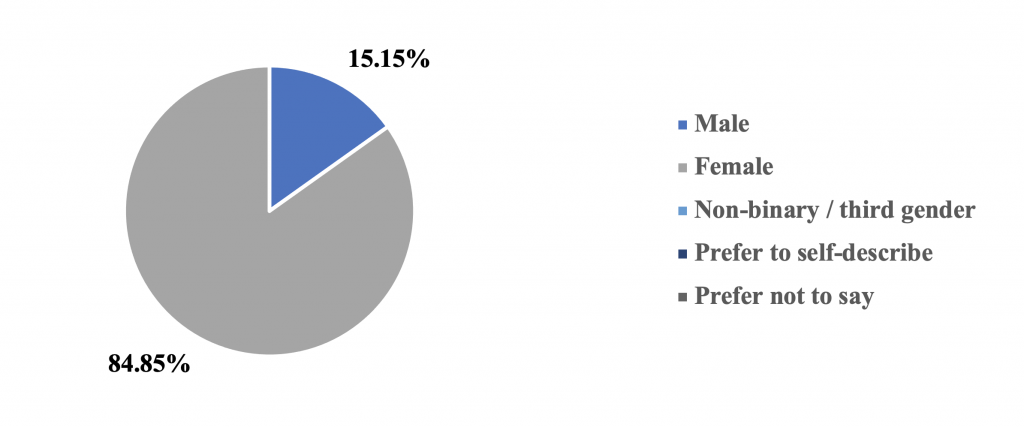

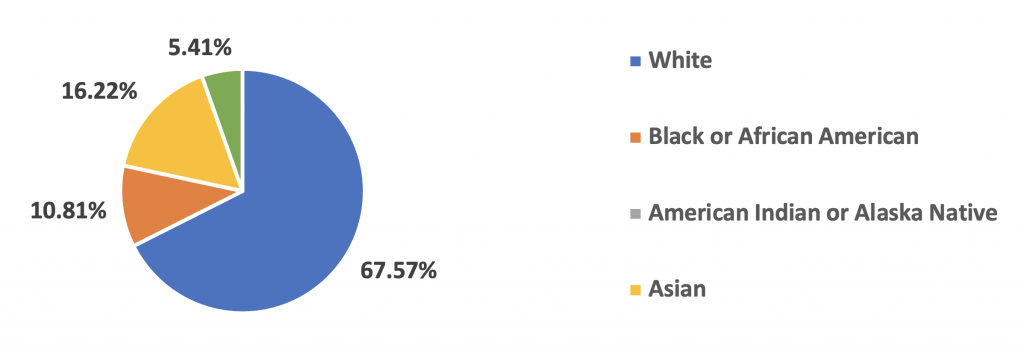

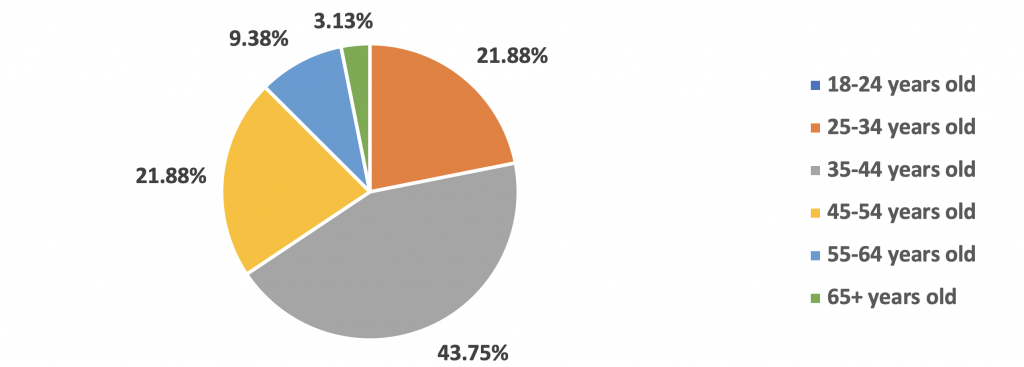

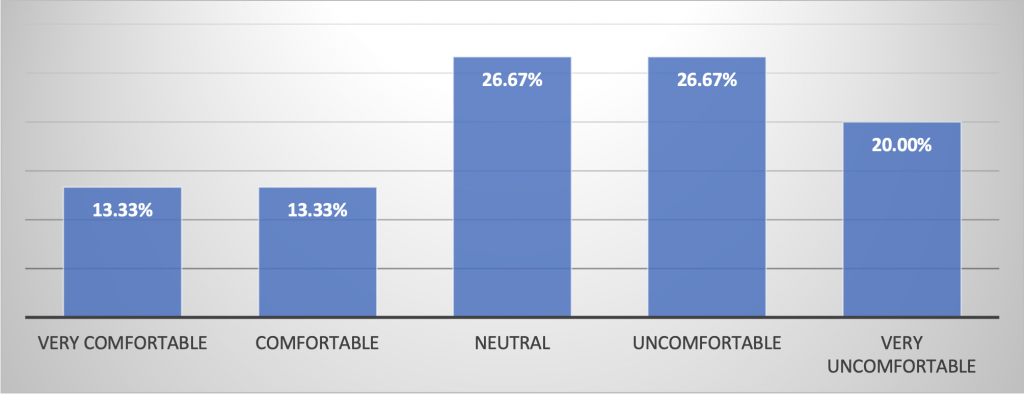

The 37 survey participants were 85% who identified as female and 15% who identified as male, 67% of which identified as White with the overall age distribution being varied (majority between 34-45). 46% of participants stated they felt uncomfortable or very uncomfortable about treating hepatitis C before completing the curriculum and 69% of the respondents had never treated hepatitis C. After completing the training 76% remarked that they felt either comfortable or very comfortable treating hepatitis C.

With the colliding epidemics, it is imperative to have trained providers who can treat hepatitis C. Since there are only 20,000 specialists, the addition of nonspecialist providers removes barriers to access and timely care. The follow-up survey assessed a compelling change in comfort level after doing the training, which supports the integration of the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease simplified guidelines in various types of practices. Curriculums designed to treat hepatis C and utilize telehealth systems will help decrease barriers and reduce the public health risk of spreading new infections.

The opioid epidemic in the United States has created a new health crisis in the 20–30-year-old demographic, increasing new hepatitis C infections.1 Once viewed as a baby-boomer disease, the CDC now recommends screening everyone 18-75 at least once regardless of risk factors for hepatitis C. In the United States today, approximately 2.4 million people have been diagnosed with hepatitis C, and up to 50% more people do not even know they have this diagnosis.2 The United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) states that hepatitis C is the most common blood-borne infection in the United States and supports the increase in new hepatitis C infections and the link to IV drug use. The USPSTF recommends screening everyone from 18-79 at least once to help to identify new infections.3 There are currently 20,000 specialists practicing (GI, Hepatology) in the United States today that have traditionally treated hepatitis C.4 To put this deficit in perspective, Dr. Arora, who helped create Project Echo at the University of New Mexico, is one of 75 GI specialists practicing in New Mexico. That translates to roughly 1 specialist for every 27,939 people, according to data from the American College of Medicine.5 With over 2.4 million people affected, it is necessary to look outside of traditional means to tackle this epidemic. Hepatitis C is a public health concern. While it is a blood-borne disease, it is easily transmitted by sharing needles, spoons, straws, and even toothbrushes. Treating and curing hepatitis C helps the community at large. One less infection means one less person can transmit the disease. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that 77 million people worldwide have hepatitis. The WHO has a goal to eradicate hepatitis by 2030 and implemented an aggressive campaign to make this goal feasible. The WHO has endorsed a simplified cascade of treatment that will involve nonspecialist providers.6 The United States has only three states on track to align with the WHO goals: South Carolina, Connecticut, and Washington State.7 Overall, the US is more aligned towards 2037. The Department of Health and Human Services has created a program called Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan A Roadmap to Elimination to create urgency to align more with WHO goals.8 This paper looks at nonspecialist providers that undertook the curriculum to learn to treat hepatitis C.

The COVID pandemic has birthed the telehealth model of medicine out of necessity. New support from The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in reimbursement for telemedicine has opened the world of medicine to new possibilities.9 This has created opportunities to reach out to the community affected by opioid abuse through telehealth to treat addiction. This removes barriers to care, such as stigma and access.The purpose of this project was to develop hepatitis C treatment curriculum for use via telemedicine through addiction medicine practices and primary care. The rules of treatment have been simplified and benefit from nonspecialist providers as a treatment option. The American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) updated their guidelines for treatment of hepatitis C to include a simplified cascade available to those patients who have never been treated for hepatitis C or have advanced disease. In other words, for treatment naïve, non-cirrhotic, without coinfection with HIV or hepatitis B patients.9 The goal is to support the goals of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) edict to eradicate hepatitis by 2030.6

In the past five years, studies and governing bodies have changed the focus of hepatitis C treatment from baby boomers to people who inject drugs (PWIDs). An epidemic of opioid abuse in the United States has changed the demographic dynamic of who the typical hepatitis C patient is. Drug use is now driving the transmission of hepatitis C. In fact, it is the number one cause of new infections, driven primarily by injection drug users. While PWIDs are the major force in new cases, many patients have not had access to care and stigma is still present. In the past, specialists were reluctant to treat PWIDs due to risk factors of reinfection and treatment noncompliance.10 Insurance companies had placed restrictions for treatment on patients proving that they had not used drugs for six months. The SIMPLIFY study followed PWIDs with the direct-acting antiviral protocols and showed that drug abuse did not affect outcomes adversely; PWIDs had similar outcome success to non-drug users. In fact, PWIDs had similar outcome success to non-drug users.11

New support from The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in reimbursement for telemedicine has opened the world of medicine to new possibilities. This is new territory since it has been in the past five years that studies and governing bodies have changed the focus of hepatitis C from baby boomers to people who inject drugs (PWIDs).12 A study of 13 Federally Qualified Community Health Centers (FQHC) in the District of Columbia used non-specialist providers to train and then treat hepatitis C. The outcomes were comparable to the specialists.11 The focus of the ASCEND phase four pilot study was to look at using direct acting antivirals in an outpatient, community health center format. The providers were given three hours of training, access to Project Echo, the 2015 AASLD guidelines, and the FDA indications where they studied only 1a genotype. The study also included co-infection with HIV and cirrhotic patients. The work done by this principal investigator was able to build on that foundation with the addition of the AASLD simplified cascade and the University of Washington hepatitis C training.11

This project created and implemented the new simplified treatment guidelines that support nonspecialist providers treating non-cirrhotic, treatment-naïve hepatitis C patients. The curriculum draws from the CDC-sponsored University of Washington Hepatitis C modules, Project Echo, a remote-based, provider-led learning environment created by the University of New Mexico in response to New Mexico having the highest rate of liver disease in the United States and a deficit of specialists to treat them.4 The educational curriculum created a model of care that can be taught easily to other interested providers.

The advanced practice providers were given an anonymous survey created through Qualtrics, a statistical survey tool. The survey had 23 questions designed to assess the comfort level, experience, opinions, and demographics of the providers who participated in the hepatitis C training. Inclusion criteria were physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and primary care physicians currently working at Workit Health with or without experience in treating hepatitis C. Exclusion criteria were those providers not treating hepatitis C voluntarily, or those for whom the opportunity had not presented itself during the study. The survey was sent out through employer-based email and placed in the Workit Health Slack channels appropriate to the providers. The providers were given three weeks to complete the survey. The educational curriculum and survey setting was Workit Health, an addiction medicine virtual telehealth-based practice. The providers were advanced practice providers, which included physician assistants and nurse practitioners with experience ranging from just out of school to over twenty years in practice. Workit Health had clinics in several states. The survey had 23 questions assessing points on treating hepatitis C, experience, comfort level and feelings about the curriculum and support.

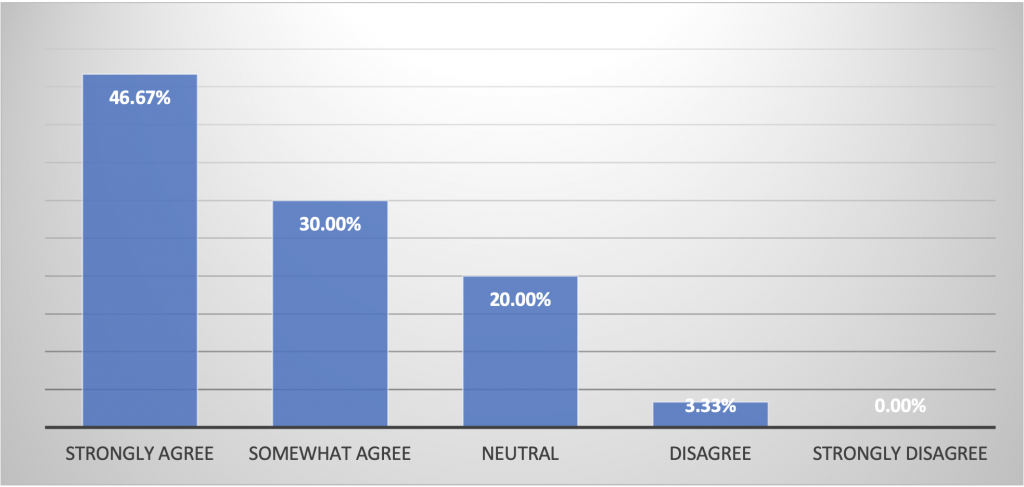

The results recorded 37 individual responses from the survey results. The sample survey had 37 completed responses with clinic participants from New Jersey, Michigan, Texas, Ohio, California, Alaska, Florida, and Oregon. Participant demographics included 85% who identified as female and 15% who identified as male. At the same time, the survey included non-binary and preferred not to disclose; these options were not utilized by those who completed the survey (Figure 1). The providers identified 67% as White, 10% as Black or African American, 16% as Asian-American, and 5% as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (Figure 2). Overall, the age distribution varied as well. The majority fell in the age group between 34-45 years of age (Figure 3). Before the training program, 69% of the responding providers had not treated hepatitis C. A complete protocol presented the opportunity to see if nonspecialist providers would be comfortable treating hepatitis C after the training. One of the survey questions asked the providers to describe their comfort level in treating hepatitis C before the curriculum. Only 13% identified as feeling very comfortable treating hepatitis C before the training. Of the survey respondents, 20% identified as very uncomfortable and 26% as uncomfortable (Figure 4). After completing the training, 47% identified as strongly agreeing to have an increased comfort level in treating hepatitis C, 30% somewhat agreed, and only 3% disagreed with feeling more comfortable. The survey questions showed a consistent theme of support helping to make the segue from training to treatment possible. Part of the curriculum included 1:1 coaching, question and answer sessions, and prerecorded trainings. The survey responses showed that providers found these tools helpful. Overall, nonspecialist providers who responded to this survey felt that curriculum and support were helpful in making a decision to treat hepatitis C.

Figure 1. Gender Identification of Providers

Figure 2. Race Distribution of Providers

Figure 3. Age Distribution of Providers

Figure 4. Provider comfort level with the idea of treating Hepatitis C before completing the Hepatitis C treatment training program

Figure 5. Provider level of Comfort Treating Hepatitis C after completing Curriculum

This study was powered by the IRB to look at provider comfort level in treating hepatitis C before and after the training curriculum. The interpretation is based on a limited cohort of providers trying out a novel program and the study does not have a comprehensive, calculated analysis. This work was primarily created to see if it was viable in real world application and enhancements will be implemented in future studies.

With 2.4 million Americans infected with hepatitis C and an increase in the opioid crisis, which is a major risk factor for viral transmission, and with the colliding epidemics, it is imperative to have trained providers who can treat hepatitis C. Since there are only 20,000 hepatitis-identified specialists in the United States, this creates barriers to access and timely care. This fact changes with the advent of the CDC and AASLD simplified treatment cascade for treatment naïve, non-cirrhotic patients to be implemented by primary care, addiction medicine and other non-specialist provider. The addition of a complete educational curriculum designed to treat hepatitis C was developed based on these guidelines and the CME courses from the University of Washington and AASLD guidelines. Programs like this can help to chip away at the 2.4 million people infected with hepatitis C. The follow-up survey assessed the comfort level and experience before and after the training. There was a compelling change in comfort level after doing the training, which supports the integration of the AASLD simplified guidelines in various types of practices.

The authors have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Dr Melchiorre is an eternal student who is committed to the underserved while working with like-minded community to make innovative, yet attainable changes for a compassionate tomorrow.

MS2 at Ross University Medical School with research, writing, editing, and publishing experience in medical education, sexual health, anesthesiology, microbiology, and more. Founding member of the Varkey-Merhavy Research Consortium producing over 25+ publications in the past 2 years, spanning various fields.

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()