Bender A, Koegler E, Rich E. Mental health and substance use concerns among transgender individuals living on the margins in Cape Town, South Africa: Preliminary selected findings from the Western Cape Stop Exploitation (RESET) study. HPHR. 2021;43. DOI:10.54111/0001/QQ4

Globally, transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) individuals face social marginalization and stigma, 1 which increases vulnerability to mental health symptoms and various diseases. 2 In Cape Town, South Africa, as elsewhere around the world, TGNC individuals are frequently compelled to support themselves through jobs that may include illicit activities such as sex work. 3 Scholars are now beginning to understand the impact of this difficult life on mental health and problematic substance use 1, 4-5 within the South African context. 6 The current study describes mental health and substance use of 24 TGNC individuals living in Cape Town. Our aim is to elucidate the prevalence of mental health and substance use concerns among a subpopulation that is vulnerable to risks of labor and commercial sex exploitation in South Africa’s second-largest city.

The 24 individuals whose experiences we describe here were drawn from a larger study to estimate the prevalence of human trafficking in Cape Town. From March through October 2021, researchers visited homeless encampments, shelters, substance use treatment centers, and other locales frequented by individuals identified as vulnerable to labor and commercial sex exploitation. Individuals who agreed to participate in the study completed a research assistant-administered questionnaire (see selected questions in Table 1) about family history, health and mental health, substance use, markers of human trafficking, and COVID-19. Participants received a grocery voucher valued at R50 ($3.38) for their time. This study was approved by the research team’s ethics committees in the U.S. and Cape Town.

Table 1. Selected interview questions from the Western Cape Stop Exploitation (RESET) Study.

Income source: Which of the following best describes your employment status? [ Full time / Part time / Not employed outside the home / Self-employed]

Service Use (selected): In the last 12 months, have you interacted with or used any of the following services? Select all that apply. Homeless shelter, safe house, or temporary housing Hospital or trauma unit Drug/alcohol treatment program Healthcare clinic or hospital South African Police Services Victim services (e.g. rape crisis, domestic violence)

Substance use and misuse (selected): Have you ever felt that you ought to cut down on your drinking or drug use? [Yes / No] Have you ever had a drink or used drugs first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover? [Yes / No]

Mental health (selected): Over the past two weeks, how often have you been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless? [Not at all / 1-7 days / 8-11 days / 12-14 days] Over the past two weeks, how often have you been bothered by not being able to stop or control worrying? [Not at all / 1-7 days / 8-11 days / 12-14 days]

|

Note: All participants were given the option to skip questions they did not wish to answer. Interviewers were instructed to probe for additional information when participants answered in the affirmative and were willing to elaborate on select responses. |

Following the input of survey results into KoboToolbox, a data collection software, the lead author selected all 2 surveys in which the participant self-identified as “transgender” or “non-binary” for basic descriptive (quantitative; SPSS) and qualitative analysis. Reported here are participants’ demographics, rates of lifetime and past-year substance use, results from CAGE-AID 7-8 (a substance use screening tool), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2), 9 a screener for depressive symptoms; and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-2) ,10 a screener for anxiety symptoms. We analyzed differences in CAGE-AID, PHQ-2 and GAD-2 mean scores between the TGNC subsample and those participants not identifying as TGNC (N = 606) with an independent samples t-test.

We present demographic information and mean scores on substance use and mental health questionnaires in Table 2. All participants were from South Africa except for one individual who migrated from Burundi over a decade prior to the interview. The majority were unhoused, living on the street, in homeless encampments, or in shelters (N=21, 77.78%). Seventeen participants (63%) disclosed they had supplemented their income during the past 12 months through sex work, with another five individuals engaged in the sex trade during their lifetime. Income sources for many of the participants were unclear, although several had received public assistance from the government during the past year (N= 7, 28%), while others were currently employed in some capacity (N=14, 51.80%). Ten participants did not report regular monthly income at all, while approximately half earned between $107 – $850 (R601 and R12800) per month, placing them within low- to middle-income brackets.

Twenty-two participants met CAGE-AID criteria for a potential lifetime substance use problem (81.5%). Twenty participants (74.07%) screened positive for symptoms of major depressive disorder and 21 (22.22%) for generalized anxiety disorder in the last two weeks as measured by the PHQ-2 and GAD-2, respectively. Eight of 24 participants (33%), without prompting, disclosed that they were HIV positive, had AIDs, or had stopped taking ARVs in sections of the survey that allowed for open-ended responses.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of transgender and non-binary participants (N=24) in a survey of individuals at risk for labor/commercial sex exploitation in Cape Town, South Africa [RESET Study].

| TGNC subsample (N= 27) | Full sample excl. TGNC (N =606) | ||

| Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent |

Gender Transgender Non-binary |

23 4 |

85.20 14.80 |

— — |

— — |

Age 18-25 25-34 35-44 45 and older |

2 11 7 7 |

7.40 40.70 25.90 25.90 |

113 198 134 130 |

19.65 34.43 23.30 22.61 |

Race Mixed race Black White Asian No answer / another race |

20 4 1 2 — |

74.10 14.80 3.70 14.80 — |

433 134 25 4 12 |

71.57 22.15 4.13 0.66 1.98 |

Education No formal education Completed primary school Completed high school Some university Completed university No response |

— 15 5 5 1 — |

— 55.56 18.50 18.50 3.70 |

7 90 409 64 23 |

1.18 14.85 67.49 10.79 3.80 |

Income source No formal employment Employed full time Employed part time Self-employed No response |

— 8 6 11 2 |

— 29.60 22.20 40.70 7.40 |

287 118 120 54 29 |

48.81 20.07 20.41 9.18 4.79 |

Monthly income R1-R400 [$0.63-$25] R1 601-R3 200 [$107-$215] R3 201-R6 400 [$215-428] R6 401- R12800 [$428-856] R12801 or more [$856 and up] No response |

1 4 8 2 2 10 |

3.70 14.80 29.60 7.40 7.40 37.03 |

20 134 85 27 24 242 |

4.84 32.45 20.58 6.54 3.96 39.93 |

Housing Lives on the street/unhoused Lives in a shelter/facility Lives in an apartment/home |

11 10 6 |

40.74 37.03 22.22 |

86 91 429 |

14.19 15.02 70.79 |

Relationship status Single Married/living together In a relationship Other |

10 7 8 2 |

37.03 25.93 14.80 7.40 |

230 166 128 134 |

37.95 27.39 21.12 22.11 |

Note: Due to rounding, percentages may not equal 100. | ||||

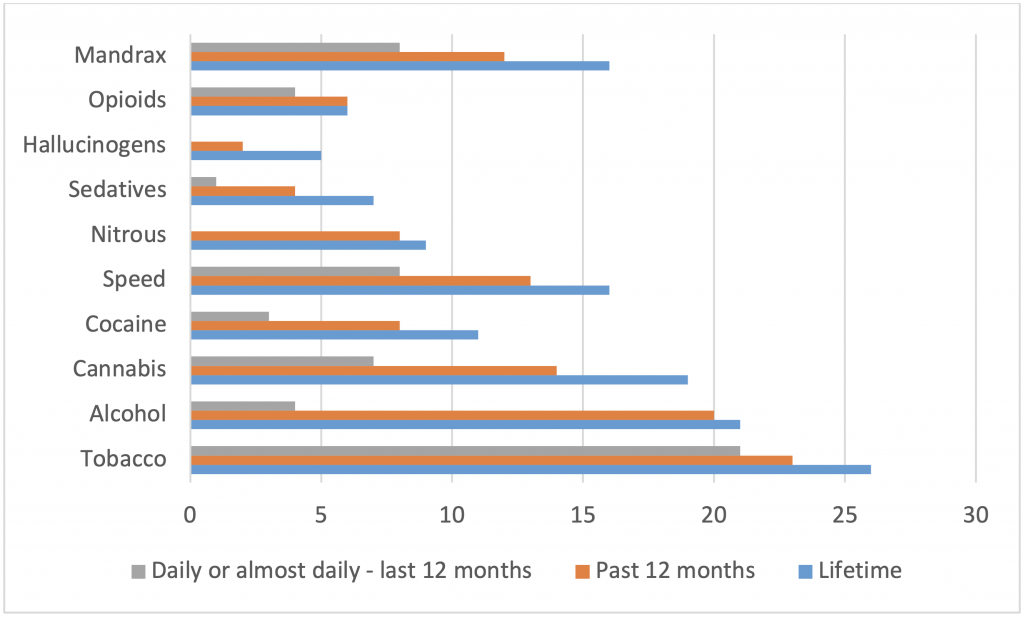

Rates of current and lifetime substance use were uniformly high across the TGNC sample (Figure 1). The most used substances over the lifetime were tobacco (N= 26, 96.30%), alcohol (N= 21, 77.80%), and cannabis (N= 19, 70.40%). . The majority of tobacco users reported smoking daily within the past 12 months (N=21, 77.80%), while eight participants (29.63%%) reported using amphetamines and/or mandrax (methaqualone; a sedative) on a daily or near-daily basis during the past year. Daily or near-daily marijuana (N=7, 25.93%) and opioid use (N=4, 14.807%) during the past 12 months was also common. Five participants (20.83%) sought treatment for drug or alcohol use within the past year.

Figure 1. Rates of lifetime and past-year substance a use among transgender and non-binary participants in a survey of individuals at risk for labor/commercial sex exploitation in Cape Town, South Africa (N=27)

a Measured via Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST).

Participants reported high rates of potential mental health concerns and problematic substance use. Many were currently unhoused or recounted a lifetime of unstable housing, which is not uncommon among TGNC people in South Africa or globally. 2,11 The majority engaged in sex work, either as a primary income source or to supplement their income. Such revelations were not unexpected coming from a high-risk sample, and indeed many of the participants who identified as cisgender also reported current homelessness or residential shelter housing (N = 47, 7.76%), problematic substance use (N = 312, 51.49%), and engaging in sex work during the last 12 months (N = 42, 7.60%).Yet the proportion of current substance use and possible substance use disorder as identified by the CAGE-AID among the TGNC subsample was striking in comparison to the (albeit high-risk) general sample. Coupled with the unsolicited disclosure by eight of the participants that they were living with HIV/AIDS revealed further concerns related to the participants’ overall health status, safer sex practices, and the lack of residential stability. The risk of acquiring HIV is 13 times higher for transgender persons than other adults, 12 and the co-occurrence of HIV and substance use problems is well-documented. 13 This entanglement of poverty, HIV/AIDS, and substance abuse is often referred to as a syndemic, 14 with negative health and social outcomes that compound and reinforce one another in a vicious cycle.

These findings are preliminary, based on a subsample of alarger study that was not aimed at addressing TGNC mental health and substance use concerns specifically. The sampling strategy relied on a combination of purposive and snowball sampling, and the locations our South African research assistants targeted for recruitment of the overall sample included homeless encampments, drop-in programs, and addiction treatment centers. While this sampling strategy was appropriate for an exploratory study aimed at identifying human trafficking prevalence among socially and economically vulnerable populations, it undoubtedly introduced selection bias into the findings reported here. As such, our results must be interpreted with caution and may not be representative of the TGNC population living in Cape Town. We present this information with the caveat that rigorous further research is necessary, as the TGNC population has too often been excluded from scholarship on human trafficking (particularly labor exploitation) and public health in general. 15

The TGNC community is as diverse and heterogeneous as any on earth 1. However, discrimination based on perceived gender transgression 16 often constrains social, economic, and other opportunities, potentially elevating risk for labor and sex exploitation 15, 17-18. Living under such stressors – conceptualized by Meyer 18 as the minority stress model – causes or exacerbates health and behavioral health problems. While South African law has established gender identity as a protected category 19 and services are available for mental and behavioral health, our findings suggest that TGNC individuals face unique barriers related to accessing affirming care 20 – particularly if they are unhoused or making a living from sex work. 3 Additional research, ideally undertaken with TGNC individuals, may further contextualize the transgender experience in South Africa and elucidate the risk of trafficking or other interpersonal violence that affects this community.

This work is made possible through support from USAID and the South African Department of Science and Innovation (DSI), as a supplement to a USAID Cooperative Agreement #7200AA18CA00009 to Purdue University. Contents reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of USAID or DSI. The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the South Africa-based field workers who were instrumental in the collection of data for this project.

The authors have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Annah K. Bender is an Assistant Professor in the School of Social Work and Affiliate Faculty in the Gender Studies Program at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. Her research interests include interpersonal violence, trauma, and substance use disorders. She received her Ph.D. and postdoctoral training at Washington University in St. Louis.

Erica L. Koegler is an Assistant Professor in the School of Social Work at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. Her research interests include human trafficking and mental health / substance use sequelae. She received her Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins University and postdoctoral training at the University of Missouri.

Edna G. Rich is a Senior Lecturer in the Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies on Children, Families and Society at the University of Western Cape. She received her Ph.D. in Social Work from the University of Western Cape.

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()