Lewis T, Iyiegbuniwe E. Barriers and facilitators of mental health services for African-American college students: a pilot study. HPHR. 2021;39. 10.54111/0001/MM1

African-American/Black college students are less likely to utilize mental health services, when compared to other races or ethnicities in the United States. It must be noted that in general, Black college students have unique experiences that affect their mental health. However, there is paucity of published research and information in the literature on the utilization of mental health services by this population of college students. This pilot study was conducted to understand and appreciate the shared barriers and facilitators that affect Black students in seeking and utilizing mental health services on campus. Primary data collection involved two qualitative focus group discussions with 20 self-identified Black/African-American undergraduate students at a university in southern California. Semi-structured interviews were administered to two focus groups. The participants were asked questions that assessed their mental health knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, and personal experiences in accessing and utilizing mental health services on campus. Results from the study identified four common themes regarding barriers and facilitators to accessing and utilizing mental health services: racism/discrimination, lack of Black mental health counselors, cultural perceptions of mental health, and stigmatization. There were no facilitators identified in utilizing mental health services on campus. The results of the study suggest a greater need to employ more Black/African-American mental healthcare providers who are counselors/psychologists. Additionally, there is need to explore the necessity for alternative mental health treatments for Black students (e.g., group discussions, or group therapy, etc.), train faculty members and campus staff on cultural competencies to minimize potential biases and discrimination, and promote diversity, equity, and inclusiveness through mental health outreach for Black students. It is hoped that these findings may play a significant role in increasing the accessibility and utilization of mental health services by Black students.

In the United States, there is a growing number of college students with mental health challenges and difficulties due to the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.There are many mental health disparities that exist within African-American communities and specifically among Black college students who are less likely to seek mental health services and treatment. 1,2,3,4,5 Common barriers to seeking and utilizing mental health services within the African-American community include cultural mistrust, stigma associated with mental health, and spiritual and/or cultural norms that affect help-seeking behaviors.6 Available published research information has shown that African-Americans have more stigmatizing beliefs about individuals with mental illnesses or those who seek mental health treatment when compared to their Caucasian counterparts.7 In addition, research has shown that African-Americans rely more on religious leaders than health professionals when seeking support for mental health .8 Researchers also reported that African-American undergraduate students generally scored significantly lower than their Caucasian counterparts in overall tests regarding attitudes, interpersonal openness, and the recognition of the need for professional psychological services.9 Therefore, there is an underutilization of professional mental health services in this population of students.

Mental health service utilization among young African-Americans warrants future research since they have high vulnerability to mental health illnesses and other stressors of significant public health importance. It must be noted that in the United States, African-American college students represent 1.3 million of the 14 million students currently enrolled in post-secondary institutions10.However, there is paucity of peer-reviewed research on the mental health status of this population.10 Moreover, there is an urgent need to address mental health issues that affect African-American college students due the ever-increasing disparities including racism, depression, and lack of social and/or academic support. 9,11,12,13 From a public health perspective, there is an ever-increasing need and growing priority to understand the mental health needs of students of color, particularly African-America students on college and university campuses. The main objective of this study was to identify access and utilization of mental health services as well as barriers and facilitators to care for Black/African-American students. This study will provide a pilot data for understanding utilization and unmet mental healthcare needs of Black students.

Qualitative data was collected through semi-structured interviews with two focus groups of students who self-identified as African-American/Black and were enrolled for classes at the main campus during the 2018 Fall Semester. Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). Focus group questions, an invitation to participate, and Informed Consent form were approved by the IRB prior to starting the study.

Participants were asked questions that assessed their mental health knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, and personal experiences with accessing and utilizing mental health services on campus. Mental healthcare services (i.e., counseling, group support, mental health resources, and mental health training) are routinely provided through pre-paid school fees. The focus group interviews were conducted at the Black Student Center (BSC), were audio recorded, transcribed, and analyzed to identify common themes.

Study participants were Fall Semester 2018 undergraduate African-American students. who were at least 18 years of age and English language. Faculty and BSC staff assisted with students’ recruitment of using the snowball technique. Additionally, flyers were posted at various campus locations and email blasts were sent to faculty, counselors, and psychologists inviting students to participate in the study.

Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim and uploaded into ATLAS.tiTM for qualitative coding and analysis. Keywords that identify barriers and facilitators in accessing mental health services were assigned into 81 codes and categorized into four common themes (i,e, Racism/Discrimination on campus, Lack of Black Mental Health Counselors, Cultural Perceptions of Mental Health, and Stigmatization) as barriers.

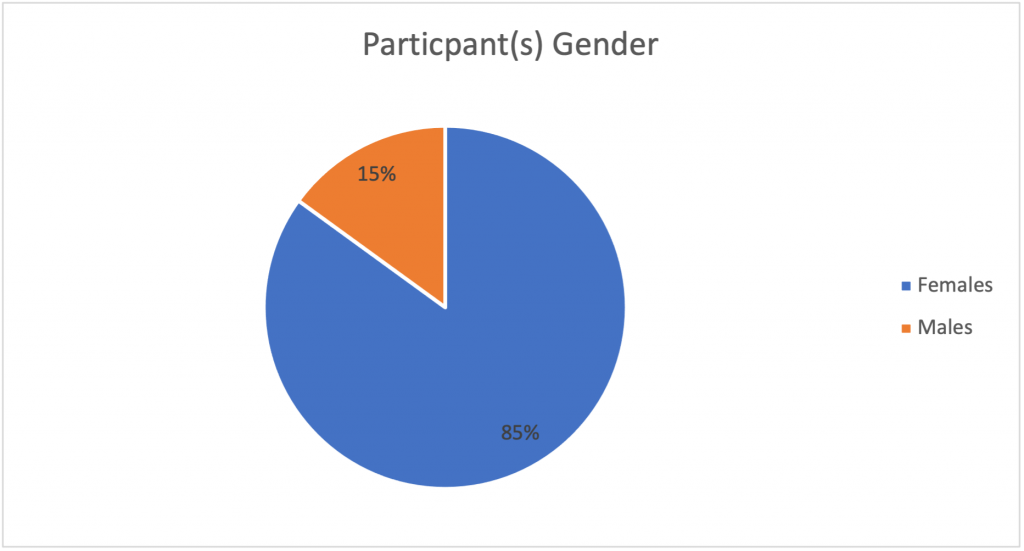

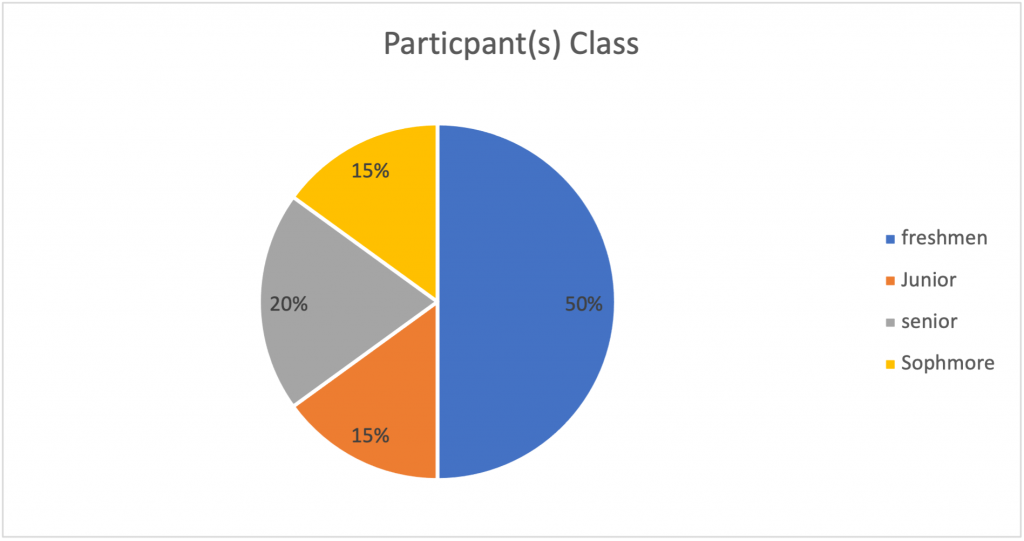

Twenty participants who met the inclusion criteria were recruited. As summarized in Figure 1, the participants were comprised of 17 females (85%) and 3 males (15%) and their year of study ranged from 15% (Sophomore and Junior) to 50% of Freshman (Figure 2). The main themes that emerged as barriers included racism/discrimination on campus, lack of Black mental health counselors on campus, cultural perceptions of mental health, and stigma. There were no facilitators identified in utilizing mental health services on campus. Details of the quotes from all the participants is summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1. Gender of focus group participants

Figure 2. Participants’ academic year of study

Table 1. Themes Identified as Barriers for Accessing and Utilizing Mental Health Services

Theme | Quote(s) |

Racism/Discrimination | “I think that we should do more things for people of color because part of it is that you need to feel like you’re in a community where you can speak out… I need to feel welcomed before I can share, and I feel most Black people don’t feel welcomed, so how do they expect you to talk to somebody when we don’t even get the greetings that we feel like we should get, or the respect we feel like we should get.”

“I feel like a lot of Black people end up wondering whether or not their Blackness is worth their mental health. If they were to fully immerse themselves in their own culture would that be worth the discrimination, or if they should allow themselves to deal with it.” |

Lack of Black Mental Health Counselors | “Someone asked me have you ever used therapy? I guess you get like 9 free sessions a semester and I said no, and they asked me why? I said unless there was a Black person in there [counseling center] that I can speak to I’m not going.”

“When it comes to mental health and stuff like that and thinking that I’m going to go sit in front of White person and expose my weakness is not registering with me… you know even if we did want to do it why would I go and expose my weakness to a White person who may possibly exploit that?” |

Stigma

| “If I were to go get counseling people would be like well… what is wrong with you? Because there is a stigma with talking about these things.”

“You don’t have time to have anxiety, you don’t have time to have multiple personality disorders, and then no matter what those illnesses were mentally within the Black culture of America it got labeled as crazy and then you don’t want to be called crazy”

|

Cultural Perceptions Related to Black Culture

| “Just growing up your taught to handle it on your own, whether it was taught to you by your parents, or maybe just the world. You’re grown into to having to feel like that and you have to just handle it on your own”

“Mental Illness is an American thing”

|

Cultural Perceptions Related to Religious/Spiritual Beliefs | “If you spoke it [mental illness] into existence then you’re causing it on yourself, or validating, feeding, and giving it strength.”

“If something is mentally wrong then you need prayer and they would take you to the Church, or Mosque and have prayers read on you”

“You know one time I opened up to my mom and she told me I need to go to the Church and then I got in trouble for talking about it.”

|

Racism and discrimination was the most frequently mentioned theme for not utilizing mental health services on campus. Participants described many events that have occurred on campus that affected their mental health. Racially insensitive comments, cultural appropriation, and racial mistreatment by students and faculty were identified as major mental health stressors. Daily occurrences of racial discrimination had negative impact on Black students’ mental health and this prevented them from seeking mental health services. The question of “what can we do?” when faced with the daily micro-aggressions due to racism and discrimination was a reoccurring theme for participants. One participant stated that he had to be “mentally tough especially dealing with racism,” while another questioned “if his mental health is worth their Blackness?”

Participants stated that they avoided seeking mental health services provided on campus due to lack of Black mental health counselors and/or psychologists. They felt that non-Black mental health counselors and/or psychologists would not be able to identify or relate to their mental health needs, including trauma from media exposure to racist abuse and violence across America.

Rather than go to mental health services offered on campus, participants sought help from older Black faculty who they believe can relate to what they were going through. However, most of those faculty members did not work in the mental health offices on campus. Furthermore, multiple participants stated that they were unaware of counseling services offered on campus and those who were aware of mental health services on campus were reluctant and uncomfortable with White counselors and service providers.

Multiple cultural perceptions of mental health were identified as barriers to seeking mental health services and were directly linked to the history of Black culture, family norms, religious and spiritual beliefs, and the constant misconception that mental health is not a Black issue.

Participants recalled that seeking mental health services was not a familiar occurrence growing up in their households. One participant recalled that not only was seeking medical attention emergent, but speaking to a therapist or counselor was perceived as an “extracurricular thing.” This was mostly due to the cost of medical treatment, which left most Black families unable to afford the cost of healthcare. Although, some participants recognized that mental health services were included in their fees, they were not aware of anyone utilizing or seeking mental health treatment in their family, hence did not know how to go about accessing it. Moreover, this gap in mental healthcare access has left all participants expressing the notion that mental health treatment was only reserved for White families.

The unique experiences related to cultural norms was also true for first generation Black students whose families did not grow up in the United States. For instance, a female participant described how the topic of mental illness was an “American thing” whenever it was discussed in her household. In fact, mental health treatment was “normally a problem” when expressions of seeking or needing help was presented in family discussions. Secondly, all participants agreed that their cultural perception of mental illness was due to spiritual or religious factors rather than biological circumstances. Additionally, religious services were used as a source of treatment in some households.

Stigma was identified as a barrier to seeking and utilizing mental health services by 17 participants who associated the topic of mental health as being a “taboo” or “weak-minded,” Eight students reported that their peers would react negatively to them seeking mental health treatment. Additionally, one participant reported that he/she felt the need to act a certain way around people or was expected to receive a backlash. Furthermore, the stigma of being labeled “crazy” featured prominently in not seeking mental health treatment, especially as this was viewed as anti-Black culture.

Participants responded that they thought it was courageous and brave to seek mental health treatment offered on campus. However, not all participants were aware of the services provided on campus or the perception of multiple barriers described above. Therefore, there were no facilitators identified in the focus groups for accessing and utilizing mental health services on campus.

A review of the data showed that rather than utilize mental health services on campus, participants lean on their peers for mental health support. A major source of refuge for participants was the emotional and social support provided at BSC and Black SistaHood organizations. All participants described the BSC as an area where they received tutoring and mentorship. Most importantly, the BSC was regarded as a safe space to escape the daily mental health stressors and have conversations regarding common issues Black college students faced. The BSC allowed them to distress and work out their problems, while educating each other on things relating to Black people and their culture.

The BSC and Black SistaHood provided students with a sense of family, a valuable attribute when dealing with mental health stressors on and off campus. As one participant stated “who else are you going to talk to?” In fact, participants in the Black SistaHood share the same beliefs and values. As a result, they often gather as a community where they collaborate with one another, eat together, and participate in extracurricular activities outside of campus as a way to distress. This alternative is important especially when considering the unique barriers that deter students from accessing services offered on campus.

The results of this pilot study revealed that mental health services and resource needs of Black students is a growing priority that have not been adequately addressed or promoted at the university campus. For one, most participants were comfortable with discussing mental health issues and stressors. However, several barriers were identified regarding access and utilization of mental health services, and these were consistent with previously published studies. A study by Greer and Chwalisz14 specifically identified several common and unique experiences that impacted mental health utilization among Black students at higher institutions to include racism, discrimination, cultural mistrust. Another study by Masuda et al. 9 reported stigma and self-concealment as systemic barriers to accessing mental health services due to lack of awareness or people not feeling culturally connected to the services provided. This feeling of lack of support was consistent with previous research.15

Spiritual/religious beliefs was identified as a barrier to seeking mental health services and according to several studies, support from religious/spiritual leaders remains a favorable alternative to mental healthcare among African-Americans.16,17,18,19

There are larger variations in mental service utilization and lower treatment among students of color when compared to white students across racial/ethnic groups in America.21 The authors concluded that the disparities in unmet mental health needs was highest among college students of color relative to white students. If left untreated, mental health can lead to depression, anxiety, or other mental health illnesses and should be addressed, especially for first year college students who reported that they preferred to handle their emotional problems on their own due to feeling embarrassed and would be hesitant to seek help in the future.22 African-American college students have disproportionally experienced excessive stress, anxiety, and depression and are more likely to underutilize or discontinue mental health services. 17 Being in a good mental health state would help all students to cope with life-changing moments, especially during the current COVID-19 pandemic, which has generally increased the risks of mental health disorders.23

No facilitators to mental health services were identified, however, this pilot study provides recommendations to aide future research in accessing mental health services for Black students. There is need to employ Black/African-American counselors to significantly reduce the effects of cultural mistrust and increase help-seeking behaviors in Black students.20 To minimize implicit bias and assist students during mental health crisis, cultural competency training is recommended for both faculty and staff. Providing the right mental health resources on college campuses will support students to be more successful in their educational and workforce careers.

Table 2. Future Recommendations for Mental Health Services

Recommendations for Mental Health Services | Quote(s) from Participants |

1. Employ Black/African-American counselors and/or psychologists that have experience with mental health stressors that plague Black adults, specifically in higher learning institutions. | “So, my question to them was when can they get somebody Black on campus that can actually help? If you’re going to help a mental issue or mental health, bring somebody Black in here. I have been asking and asking and asking. I have been talking to I don’t know how many people. Why don’t we still have anybody here that’s Black?” |

2. Implement culturally sensitive counseling interventions, such as group discussions and congregations that are conducted in the Black Student Center, can help facilitate Black students to release any mental health stressors that they may have | “I prefer this way [group discussion] instead of going to see an Asian or White doctor. If I go to see them and talk to them, I have to explain things that they have no concept of. I would rather go around my people to talk to somebody who can help me with that and then you also get to have fun. So, you get to release some stress and maybe help correct an issue. Now you can handle all of those things and be comfortable the whole time.” |

3. Cultural Competency Training for Faculty Members & Staff | “If we were to go in to one of these meetings or to one of these people and say you know what! I was just looking on the news and I just saw a Black man have his house invaded by the police, he was shot in front of his kids and his wife and then they said they had the wrong house. Or, if he talks about the guy that just got lynched, they [mental health counselors] have absolutely no understanding of what he’s going through, mentally, physically, emotionally…none of that.” |

4.Promote Inclusion Through Mental Health Outreach for Black Students | “There aren’t posters on our website. You don’t see any African-American counselors or students who are African-American going to receive help. So, it’s like is it [mental health services] for me? I’m not sure…”

|

There is an ever-increasing priority and growing need to understand the mental health needs of students of color, particularly African-America students on college and university campuses. This pilot study identified shared barriers and facilitators for Black/African-American students in seeking and utilizing mental health services at a university campus. Barriers that participants identified included racism and discrimination, lack of Black mental health counselors and/or psychologists, cultural perceptions and stigma. In contrast, there were no facilitators identified in seeking mental health services on campus and this was consistent with previously published research studies. Students’ mental health influence how they act, think, and feel, hence the mental need and desire for university administrators to consider the provision of mental health services as a top priority. Overall, the key findings from this study would be useful in bridging the existing gap in knowledge and the literature regarding mental health by shedding light on Black college student’s perceptions and ability to access and utilize mental health services on their college campus. We hope that this study will shed some light in providing pilot data for understanding the unmet mental healthcare needs and service utilization among Black/African-American students.

The authors would like to thank Cheryl Berry, MEd for her contributions during data collection and analysis for this paper.

The authors have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Informed Consent

Title of Project: Barriers and Facilitators of Mental Health Services for African-American Students

Invitation to Participate

Dear Participant:

You are invited to participate in a research study titled “Barriers and Facilitators of Mental Health Services for African-American Students.” Before agreeing to participate in a research study, please read this form very carefully and ask any questions that you may have or if you need additional information. You must be 18 years or older to participate in the study.

The information provided during the focus group will only be used by the investigator to identify the shared barriers and facilitators for African-American students in accessing and utilizing mental health services on campus. None of the information provided will be used to identify the respondents. By signing this Consent Form, the participants are giving their implied consent.

PURPOSE OF STUDY:

You are being asked to take part in a research study. The purpose of this study is to gain a better understanding of the common barriers and facilitators of seeking and utilizing mental health services on campus. If you agree to participate, you will be one of 25 participants in this research study that aims to play a significant role in treatment of mental illness in African-American students on campus.

STUDY PROCEDURES:

If you agree to participate in the study, you will be required to do the following:

RISKS AND INCONVENIENCES:

There are minimal risks and inconveniences associated with participating in the study. These may include:

SAFEGUARDS:

In order to minimize the risks and inconveniences, the following measures will be taken:

BENEFITS:

There will be no direct benefit to you for your participation in this study. However, the information obtained from this study will allow participants to start a conversation about mental health among black students in the community. Also, findings from this study will help identify crucial areas in which higher education counseling center staff may intervene and educate African-American college students. Lastly, results from this study can assist in possible interventions to implement for further research studies that may help both African-American and other minority students on campus.

CONFIDENTIALITY:

Your responses to the interview questions will be anonymous. None of the information provided will be used to identify the respondents.

Each participant will be assigned an identification number or code. The investigator will not collect names, birthdates, addresses, phone numbers, and social security numbers from participants. The data collected will only be used for research purposes. All notes, interview transcriptions, and any other identifying participant information will be kept in a password protected laptop device.

The results of this study may be used by the investigator to generate reports, presentations, and/or publications as part of the requirement for an integrative learning experience.

CONTACT INFORMATION:

If you have questions at any time about this study, or you experience adverse effects as a result of participating in this study, you may contact with any further questions. In addition, if you have any questions regarding your rights as a participant in this research, please contact the Institutional Review Board (IRB) office.

VOLUNTARY PARTICIPATION:

Your participation in this study is voluntary. It is up to you to decide whether or not to take part in this study. Withdrawing from this study will not result in any penalty and will affect your relationship with the investigator.

INCENTIVES FOR PARTICIPATION:

Snacks and drinks will be provided for participants during the focus group discussion.

PARTICIPANT’S CONSENT:

Printed Name Participant’s Signature Date

Focus Group Discussion Questions

Defines general characteristics of participants. Demographics were aggregated to preserve participants’ identity and confidentiality.

Demographic Questionnaire

Freshman Sophomore Junior Senior Postgraduate Studies (Masters/PhD)

Tasha Lewis is a Community Health Promotion Specialist with over 11 years of diverse healthcare experience. She earned her MPH in Health Promotion and Education at California State University San Marcos. Her research areas include maternal and infant health, and health disparities in minority communities.

Dr. Emmanuel Iyiegbuniwe earned both the MSPH and PhD degrees in Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences from University of Illinois at Chicago and MBA from Western Kentucky University. He is an Associate Professor of Public Health at California State University San Marcos (CSUSM) and has over 28 years of academic, administrative, and consulting experience. He served as the inaugural Director for the MPH program at CSUSM with concentrations in Global Health and Health Promotion & Education. He teaches several public health courses and conducts research on the social and environmental determinants of health.

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()