Mitchell C. Philadelphia fetal and infant mortality review/ HIV summary report 2010-2021. HPHR. 2021:38. DOI:10.54111/0001/LL2

Most new HIV diagnoses are attributed to heterosexual contact in young, Black women. The risk of perinatal transmission, either through vertical transmission or breastfeeding, is about 25% with no intervention. However, regular antiretroviral therapy (ART) can lower this risk to less than 1%. The FIMR/HIV Prevention Methodology was adapted from the Fetal and Infant Mortality Review (FIMR) to improve services and resources for women living with HIV and their HIV-exposed infants. Through information gathering, case reviews, and community action team meetings, FIMR/HIV is effective in addressing systemic barriers that contribute to HIV incidence. Since 2010, a Philadelphia-based Case Review Team (CRT) of interdisciplinary professionals has reviewed more than 200 cases eligible for review. Twice a year, a Community Action Team (CAT) comprised of organizational professionals meets to identify noted healthcare gaps and suggest recommendations and action steps for barrier-focused subcommittees moving forward. As a result, referrals to and engagement in intensive perinatal case management, prenatal care, and HIV care have increased, and the number of women lost to follow-up postpartum has decreased. In every case reviewed in 2020, at least some prenatal care was received, a milestone in the decade-long history of FIMR/HIV. Next steps for Philadelphia’s FIMR/HIV include adding cross-committee activities and subcommittees related to current issues, as well as potentially adding a third CAT meeting and expanding membership to be inclusive of area hospitals with maternity services.

Of the 37,832 new cases of HIV in 2018, only 19% were among women. However, most female diagnoses were attributed to heterosexual contact, and more than half of new diagnoses occurred among Black/African American women between the ages of 25 to 34.1

Perinatal HIV transmission, HIV passed from mother-to-child during pregnancy, labor and delivery, or breastfeeding, has decreased by more than 95% since the early 1990s and 54% between 2014 and 2018 in the U.S.1 Women who are undiagnosed, not in HIV care, unaware of their pregnancy status, non-adherent with medications, or living in poverty without sufficient access to care are most likely to pass HIV onto their children.2

Pregnant women diagnosed with HIV can prevent perinatal transmission by visiting their health provider regularly, taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) daily to achieve an undetectable viral load, opting for a C-section in the case of an HIV viral load greater than 1,000 copies/ml, and abstaining from breastfeeding. The risk of perinatal transmission is less than 1% if women continue taking ART medication every day for the duration of pregnancy, receive intravenous AZT during the birth process if they have a detectable viral load, and give HIV medication to the infant for 4-6 weeks after delivery.2 The risk of perinatal infection with no intervention is approximately 25%, and the risk is highest if the mother acquires HIV during her pregnancy.3,4 Ultimately, the Fetal and Infant Mortality Review as applied to HIV (FIMR/HIV) aims to eliminate all perinatal HIV transmissions.

A 2020 cohort study of births among HIV-positive women found that women living in neighborhoods with high crime rates were more likely to have poor ART adherence, while women living in neighborhoods with access to educational resources were more likely to have their HIV under control. 5 This study used the ecological model of health behavior as a conceptual framework, which states that individual, interpersonal, community, and societal factors influence health outcomes. According to this theory, health policies and programs aimed at improving women’s access to healthcare can positively impact HIV prognosis and maternal and child health outcomes. 6 A recent initiative, Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S., is a Philadelphia-based project that focuses on “priority populations” (Black and Hispanic/Latino men who have sex with men, youth aged 18−24 years, and transgender people who have sex with men) and uses interdisciplinary teams, chart abstraction, and interview data to identify themes and service gaps among the cases. 7

FIMR/HIV Prevention Methodology is based on the methodology of the Fetal and Infant Mortality Review (FIMR). In 2005, three pilot sites (Baton Rouge, Louisiana; Detroit, Michigan; and Jacksonville, Florida) implemented the FIMR/HIV Prevention Methodology over the course of two years based on their previous experience with FIMR. At the end of the trial, all three sites reported integration of HIV care with family planning and improved preconception health information dissemination. The original FIMR is a community-based, action-oriented process with the goal of improving services, systems, and resources for women and their babies when a fetal or infant death has occurred. This methodology was designed by a public–private partnership between the federal Maternal Child Health Bureau and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to address root causes of infant mortality. Multidisciplinary teams of health care professionals analyze confidential cases and examine themes to help better understand how women’s experiences may have impacted their health outcomes.8 The three steps of FIMR are: information gathering, case reviews, and community action.

First, information about the death is gathered from public health and medical records. Then, the mother has the option to complete an interview. Next, a Case Review Team (CRT) assembles to review the summary details of a case and interview, if it is available. This team consists of medical providers, community advocates, and other representatives of institutions, professional organizations, and private agencies that provide resources for women and their families. After reviewing the case, the team identifies gaps in care and makes recommendations for improvement. Lastly, members of a Community Action Team, a broader group of organizational leaders recruited for their ability to create systems changes, review recommendations made by the CRT and noted trends in barriers to care, best practices, and consistent case themes (see Table 1). Members of the CAT either have the political, organizational, and/or fiscal authority to make a significant impact within the community and offer an informed perspective on behalf of pregnant and parenting women and their families.

FIMR/HIV has a similar design and implementation as the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. initiative. As a result of FIMR/HIV’s success in Baton Rouge, Detroit and Jacksonville, as well as the literature supporting an interdisciplinary, multilevel approach to reducing perinatal transmission, the Philadelphia Department of Public Health received direct funding to implement FIMR/HIV within the jurisdiction in 2012. After two years, the funding continued through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV Prevention Grant. In 2018, FIMR/HIV became a requirement under the CDC Integrated HIV Prevention and Surveillance Grant.

Table 1. FIMR/HIV Perinatal Themes 2010-2020

Stage in Pregnancy | Theme |

Preconception | Reproductive health counseling including contraception and preconception counseling |

| Documentation of contraception and pregnancy intention; Intimate partner violence |

| Missed PrEP opportunities when STIs diagnosed |

| Access to and consistent use of contraception (in most cases reviewed, pregnancies were unplanned and unintended) |

Prenatal | Late entry to prenatal and HIV care (no clear recommendation) |

| Inconsistent prenatal or HIV care |

| Consistent Perinatal-specific Medical Case Management referrals and lack of engagement by clients in perinatal case management |

| Mental health and substance use screening and treatment access |

Maternal HIV Care | Viral suppression by the time of delivery |

| Diagnosis prior to delivery |

| Attendance at postpartum HIV follow-up visit |

| HIV care engagement at 12 months postpartum |

| Viral suppression at 12 months postpartum |

Intrapartum | Concurrent hepatitis C/B infection |

| Positive toxicology screen at delivery |

| No documentation of ART prescription at discharge |

| Cases with no prenatal care being diagnosed at the time of delivery |

Postpartum | Pediatric and postpartum appointments made prior to hospital discharge |

| Postpartum contraception type (implantable/IUD, injectable, OCP, BTL, condoms only, none) |

| Behavioral health access and follow up |

| Access to and consistent use of contraception postpartum |

Pediatric | DHS involvement |

| Loss of infant follow-up data due to move out of jurisdiction |

| Adequate pediatric antiretroviral prophylaxis and use of high-risk protocol |

The FIMR/HIV Prevention Methodology was adapted from the existing FIMR methodology to focus on perinatal HIV exposure rather than infant death. While continuing to adhere to all confidentiality and improvement measures, FIMR/HIV invites those with expertise in perinatal HIV care and/or those who work with women in the HIV-positive community onto its case review and community action teams.

The Case Review and Community Action teams vary based on the community. The FIMR/HIV Prevention Methodology adheres to the CDC recommendation to review all cases of perinatal infection as sentinel events. FIMR/HIV collects comprehensive qualitative and quantitative data to allow members of the committee to examine the health, social, cultural, educational, safety, and economic systems that contribute to perinatal HIV exposure and, more rarely, transmission.

Cases are eligible for review if they meet one or more of the following criteria: perinatal HIV transmission, late maternal HIV diagnosis, lack of or inadequate prenatal care, lack of maternal HIV treatment or inadequate viral suppression, or lack of ART prophylaxis during labor and delivery. Information for case reviews is obtained from a variety of sources, including physician/hospital records, reports from home visits, WIC documentation, and social services.

FIMR/HIV was determined not to be human subjects research by the Philadelphia Department of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

The first Philadelphia Case Review Team meeting took place in September 2011. The team is composed of multidisciplinary professionals, including clinical HIV, OB/GYN, and behavioral health providers, managed care representatives, social workers, case managers, Department of Human Services, Substance Use Disorder providers, homeless agencies, advocacy groups, and community members. A case is defined as an HIV-exposed infant or fetus greater than or equal to 24 weeks gestation. Prenatal care, labor and delivery, and pediatric care data are collected through chart abstraction, and a maternal interview is conducted when possible.

In total, between 2010 and 2021, 206 cases of women living in Philadelphia were reviewed, six of which resulted in perinatal transmission.

In 2010, the first year of the FIMR/HIV Case Review, six cases were reviewed from September to November with all births taking place in 2010. No perinatal transmissions or maternal deaths occurred. Half of the cases received some level of prenatal and maternal HIV care. One infant death occurred due to SIDS.

In 2011, 21 cases were reviewed, with births in 2011, resulting in two perinatal transmissions and one fetal death. Eight women reported unintended pregnancy, and seven did not report contraception use. Sixteen women did not report prenatal care; five had inadequate prenatal care, and six were not engaged in maternal HIV care. Fourteen women were active substance users, 11 had a history of mental health issues, four had unstable housing, and two were incarcerated during pregnancy. Eight women were not aware of their HIV status before pregnancy.

In 2012, 17 cases (including one twin gestation) were reviewed, with births occurring in 2012, resulting in zero transmissions. Nine maternal interviews were obtained. Maternal ages ranged between 21 and 39, and three women were foreign-born. Fourteen women had no documented use of contraception, and three had an intended pregnancy but were unaware of their HIV status. Ten women were aware of their HIV status, but only eight engaged in HIV care. Four women not engaged in prenatal care, and 10 were not referred to perinatal case management. Five women were active substance users, and three had previously diagnosed mental health issues. Two women visited the emergency room, three had unstable housing, and two were incarcerated during pregnancy. In one case, the mother refused to give AZT to her infant.

In 2013, 23 cases were selected for review (including one twin gestation), with births occurring in 2011, 2012 and, 2013, resulting in one transmission. Two infant deaths from chorioamnionitis and SIDS occurred. Six women underwent a maternal interview. Maternal age ranged from 19 to 44, and five women were foreign-born. Fifteen women had no documented contraception use, and seven had an unintended pregnancy. Sixteen women were aware of their HIV status, but only 14 were previously engaged in HIV care. Three women received no prenatal care, and only 13 were referred to perinatal case management. Eleven women were active substance users, 11 had previously diagnosed mental health issues, three visited the emergency room, and nine had unstable housing during pregnancy. Eight women were lost to care postpartum.

In 2014, 23 cases were selected for review, with births in 2012 and 2013, resulting in zero transmissions. Maternal age ranged from 21 to 47 years old, and two mothers were foreign-born. Ten women had no documented use of contraception, and five women had unintended pregnancy. Eight women were active substance users, 10 had previously diagnosed mental health issues, three visited the emergency room, and three had unstable housing during pregnancy. For the first time since perinatal case management became available, all 23 mothers were referred and received it. However, eight women had inconsistent ART usage. Two women received no prenatal care and were among the five cases diagnosed at labor and delivery. Five women had a positive toxicology test at delivery, and six had Department of Human Services (DHS) involvement due to substance use. Pediatric AZT was administered in all 23 cases.

In 2015, 21 cases were selected for review, with births in 2013 and 2014, resulting in zero transmissions. Maternal ages ranged from 18 to 41, and two women were foreign-born. Twelve women had no documented use of contraception, and eight women had an unintended pregnancy. Four women were unaware of their HIV status prior to pregnancy. Seven women were active substance users, six had previously diagnosed mental health issues, three visited the emergency room, and eight had unstable housing during pregnancy. Perinatal or HIV case management was offered in 16 cases. Four women had no prenatal ART use, and five had inconsistent ART use. Three women were lost to follow-up postpartum, and twelve had DHS involvement due to maternal substance use.

In 2016, 17 cases were reviewed, with births in 2014 and 2015, resulting in zero transmissions. One woman was foreign-born and experienced a language barrier with providers. The maternal ages ranged between 18 and 41. Six women had an unintended pregnancy, and two were unaware of their diagnosis prior to pregnancy. Two women received no prenatal care, and 15 had inconsistent ART usage. Eight women were active substance users, 13 had previously diagnosed mental health issues, five had unstable housing, and three utilized emergency department services during pregnancy.

In 2017, 16 cases were reviewed, with births in 2012, 2014, 2015, and 2016, resulting in two perinatal transmissions (infants born in 2015), two intrauterine fetal demises (placental abruption with corresponding maternal cocaine use and encephalocele and amniotic band syndrome) and one infant death. he maternal age ranged from 19 to 34, and one maternal interview was obtained. Four women had an unintended pregnancy. Eleven women were active substance users, six had previously diagnosed mental health problems, and 10 had unstable housing during pregnancy. Three women were unaware of their HIV status prior to pregnancy, and all 16 had some type of case management referral. Three women were incarcerated during pregnancy, and one case had DHS involvement. For the first time, hepatitis C testing and neonatal abstinence syndrome were reported; four women were tested for hepatitis C as part of their prenatal labs, and one infant was diagnosed with neonatal abstinence syndrome.

In 2018, 17 cases were reviewed, with births in 2016, 2017 and 2018, resulting in zero transmissions and zero infant or maternal deaths. Maternal age ranged from 19 to 39. Four women reported an unintended pregnancy, and only two were aware of their HIV status prior to pregnancy. Six women were active substance users, eight had previously diagnosed mental health issues, and 12 had unstable housing. Three infants had neonatal abstinence syndrome, and 10 women were tested for hepatitis C. Three women were incarcerated during pregnancy, and 10 had DHS involvement due to positive toxicology screens and incarceration postpartum.

In 2019, 18 cases were reviewed, with births occurring in 2017 and 2018, resulting in no transmissions or infant deaths. Maternal age ranged from 22 to 38, and two women were foreign-born. Six women had an unintended pregnancy, and 13 had inconsistent ART usage. Two women received no prenatal care, and four were unaware of their HIV status prior to pregnancy. Eight women were active substance users, 10 had previously diagnosed mental health issues, eight visited the emergency room, and six had unstable housing during pregnancy. Eight women were undetectable at some point during pregnancy, and 11 were undetectable postpartum. One infant had neonatal abstinence syndrome, and 11 infants received IV AZT. Three mothers had positive toxicology tests at delivery, and 17 women were tested for hepatitis C. Unfortunately, one mother committed suicide seven months postpartum.

In 2020, 14 cases were reviewed (including one twin gestation) with births occurring in 2018 and 2019, resulting in zero transmissions. Maternal age ranged from 18 to 44; one maternal interview was obtained, and three women were foreign-born. Ten women had an unintended pregnancy, and three were unaware of their HIV status prior to pregnancy. One woman was diagnosed after labor and delivery due to confusion regarding her HIV diagnosis, as she did not know how to interpret her test result. Five women were active substance users, six had previously diagnosed mental health issues, and six had unstable housing during pregnancy. In one case, the patient went to the emergency room 24 times, mostly for falls. Three women had positive toxicology test results at delivery, and eleven had inconsistent ART adherence. Two infants had neonatal abstinence syndrome, and 10 mothers were tested for hepatitis C. Six cases were virally suppressed by the time of delivery, and all infants received IZ AZT at delivery.

In 2021, 13 cases were reviewed, with births occurring in 2019 and 2020, resulting in one transmission, one fetal demise, and one maternal death. Maternal age ranged from 25 to 41, and four women were foreign-born. Six women had an unintended pregnancy, and five were unaware of their HIV status prior to pregnancy. Seven women had inconsistent ART adherence. Four women were active substance users, six had previously diagnosed mental health issues, four visited the emergency room, and four had unstable housing during pregnancy. Four women had positive toxicology test results at delivery, and four were incarcerated during pregnancy. One infant had neonatal abstinence syndrome, and four mothers were tested for hepatitis C. Eight cases were virally suppressed by the time of delivery; nine infants received IZ AZT at delivery.

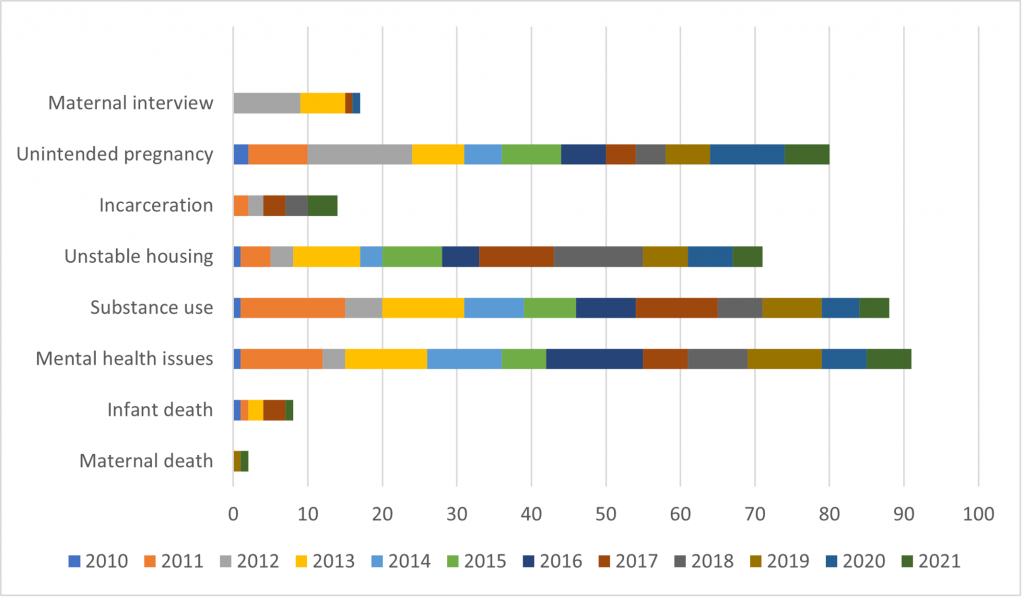

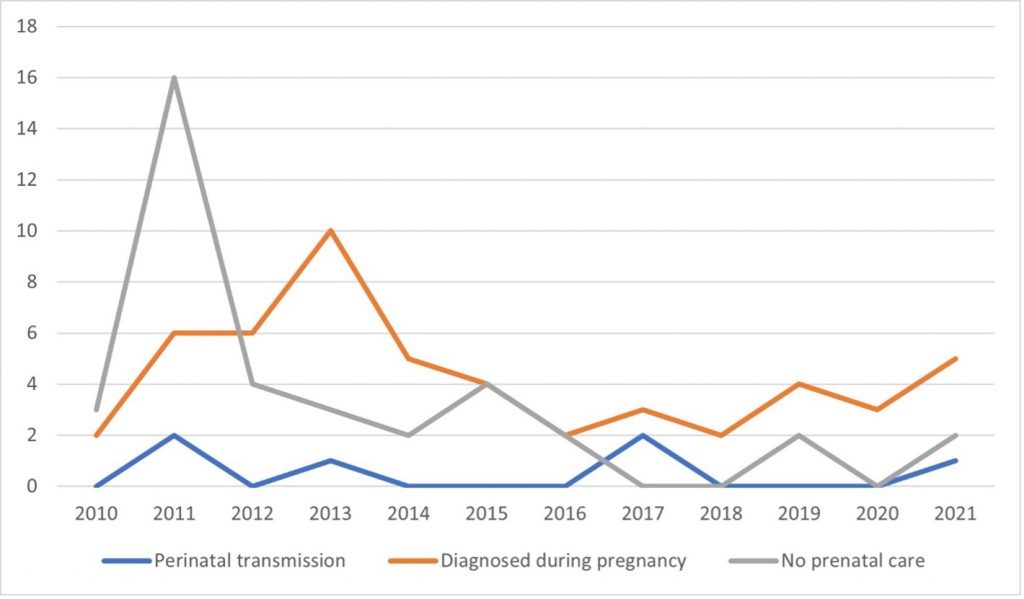

Overall, the incidence of perinatal transmission has decreased within the past decade. In 2020, for the first time since the FIMR/HIV project began, all mothers whose cases were reviewed received at least some prenatal care. Perinatal case management referrals increased from 28.5% in 2011 to 84.6% in 2021. The number of women diagnosed during pregnancy was on the decline from 2013 to 2016 but began to rise again from 2017 to 2021 (see Figure 1). The prevalence of previously diagnosed mental health conditions does not have a consistent pattern. The prevalence of unstable housing increased from 17.6% in 2012 to 30.8% in 2021. Substance use has also increased from 19.0% in 2011 to 30.8% in 2021. Incarceration rates have plateaued; however, these rates were usually low in comparison with other measures (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Summary Data 2010-2021

Figure 2. Main Three Findings 2010-2021

From 2016 to 2021, the number of emergency C-section deliveries decreased from five (29.4%) to zero. DHS involvement following labor and delivery is declining, but it is still highest among women with active substance use disorder. Currently, infants are receiving pediatric antiretroviral prophylaxis of zidovudine (AZT) plus nevirapine (NVP), or triple-drug antiretroviral prophylaxis of AZT/NVP/lamivudine (3TC), as is recommended for high-risk perinatal exposure, more often than AZT monotherapy. Between 2012 and 2020, the number of women lost to follow-up in the postpartum period decreased. Maternal and infant deaths have remained low over the past decade and are neither increasing nor decreasing.

Table 1. FIMR/HIV Perinatal Themes 2010-2020

Stage in Pregnancy | Theme |

Preconception | Reproductive health counseling including contraception and preconception counseling |

Documentation of contraception and pregnancy intention; Intimate partner violence | |

Missed PrEP opportunities when STIs diagnosed | |

Access to and consistent use of contraception (in most cases reviewed, pregnancies were unplanned and unintended) | |

Prenatal | Late entry to prenatal and HIV care (no clear recommendation) |

Inconsistent prenatal or HIV care | |

Consistent Perinatal-specific Medical Case Management referrals and lack of engagement by clients in perinatal case management | |

Mental health and substance use screening and treatment access | |

Maternal HIV Care | Viral suppression by the time of delivery |

Diagnosis prior to delivery | |

Attendance at postpartum HIV follow-up visit | |

HIV care engagement at 12 months postpartum | |

Viral suppression at 12 months postpartum | |

Intrapartum | Concurrent hepatitis C/B infection |

Positive toxicology screen at delivery | |

No documentation of ART prescription at discharge | |

Cases with no prenatal care being diagnosed at the time of delivery | |

Postpartum | Pediatric and postpartum appointments made prior to hospital discharge |

Postpartum contraception type (implantable/IUD, injectable, OCP, BTL, condoms only, none) | |

Behavioral health access and follow up | |

Access to and consistent use of contraception postpartum | |

Pediatric | DHS involvement |

Loss of infant follow-up data due to move out of jurisdiction | |

Adequate pediatric antiretroviral prophylaxis and use of high-risk protocol |

*X= completed

As part of the case review process, the Case Review Team identifies gaps and missed opportunities in prenatal, HIV, intrapartum, postpartum, and pediatric care at the system and provider level (see Table 2). Preconception gaps in care included the need for support and services for individuals and/or their family members to navigate health systems, especially for individuals with behavioral health issues; contraception discussion and distribution; and improved dissemination of updated perinatal HIV management guidelines among obstetric providers and infectious disease specialists not affiliated with academic medical centers.

Prenatal gaps included the discontinuation of psychiatric medications during pregnancy, either by the patient herself or by a provider, and lack of access to mental health care; a lack of investigation into red flags for intimate partner violence (e.g. reports of “falls”) when they are chief complaints of emergency department visits; inconsistent interpreter and ASL services resulting in either the inappropriate use of a family member for translation assistance or discomfort in divulging sensitive and personal information to a stranger; and health and reading literacy issues.

Labor and delivery gaps included inconsistent documentation of the depression screening results and poor communication between HIV, outpatient, and inpatient obstetric providers, causing an inability to access to prenatal records, particularly with transfer of care.

Maternal postpartum gaps included not scheduling postpartum appointments prior to discharge from the hospital; inconsistent use of nurse home visitors; no preconception and postpartum contraception discussion at delivery; no documentation about access to social services; and maternal reluctance to accept the offer of nurse home visits due to privacy and confidentiality concerns.

Infant postpartum gaps included loss of insurance after relocation out of the original jurisdiction (insurance not covering home visits or pediatric nurses) and verifying whether the mother continues HIV care after labor and delivery.

HIV care gaps included poor care coordination between HIV and prenatal care providers; no HIV care records for women living out of jurisdiction prior to pregnancy; infrequent viral load testing despite being in OB care; and no CD4 counts during pregnancy. Moreover, engaging women in care is an ongoing continuity of care challenge.

This case review did have some limitations, however. Since it was a sentinel case review, it was not necessarily representative of all perinatal exposures in Philadelphia within the time period. In addition, because most women did not complete an interview, there are potentially missed opportunities that were not captured by the raw data alone. Neonatal abstinence syndrome and hepatitis C testing were not regularly measured until 2017, and inconsistent data collection resulted in missing data between 2013 and 2018. Lastly, outdated contact information may have limited outreach for interviewers and made postpartum follow up difficult.

In the future, Philadelphia’s FIMR/HIV project strives to add cross-committee collaborative activities and new subcommittees focused on relevant topics, such as substance use disorder and breastfeeding. The Community Action Team hopes to give the committees more time to develop plans with each other, in addition to scheduling a third meeting on the calendar. Finally, the CAT proposes broader membership and representation from all Philadelphia hospitals with maternity services. This includes a hospital discharge planner, labor and delivery nurse, community behavioral health specialist, local hospital administrator, federally qualified health center director, Medicaid managed care director, and a consistent representative from the Department of Behavioral Health. Furthermore, the Philadelphia FIMR/HIV project has been successful in reducing the incidence of perinatal transmissions and diagnoses during pregnancy, as well as increasing the incidence of prenatal care and viral suppression at labor and delivery.

The author has no relevant personal, commercial, academic, or financial disclosures or conflicts of interest. The author contributed to the creation of the submission, and grant HPHR permission to review and (if selected) publish their work. The submission is not under consideration by another publication and/or has not previously been published elsewhere.

I would like to thank Kristin Walker, the Perinatal HIV Prevention Project Coordinator, Debra Dalessandro, the Director of Public Health Training and Technical Assistance, and Dr. Kathleen Brady, the Medical Director at the Health Federation of Philadelphia for assisting in collecting FIMR/HIV data and editing this research article.

Christina Mitchell is a first-year master’s student with a concentration in epidemiology and biostatistics in the 4+1 Masters of Public Health accelerated program at Temple University. She graduated with her Bachelor of Science from Temple in May 2021 and is currently working as a research assistant at the Kornberg School of Dentistry and an intern at the Philadelphia Children’s Alliance while completing her master’s degree.

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()