Ammar A, Boykeb A, Vitala A, Hamzah R, Javed A, Rolle M, Park K. Out-of-pocket cost of neurosurgical bellwether procedures: a systematic review. HPHR. 2021; 32.

DOI:10.54111/0001/FF12

33 million people worldwide face catastrophic health expenditures each year from surgery and anesthesia. This study aims to collate the current literature on out-of-pocket (OOP) costs of Bellwether neurosurgical procedures in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to provide a basis for calculations of financial burdens, determine deficits in the literature, and guide further research efforts.

MEDLINE/PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar and Relief Web were searched for articles containing data on OOP costs for neurosurgical Bellwether procedures in LMICs. Of 415 relevant publications that were identified, 4 met inclusion criteria.

One study from Uganda found median direct medical and non-medical costs to be USD 118.06 and USD 84.33, respectively. A study from Vietnam found the total medical care and surgery for head injury OOP cost to be USD 287.30 and USD 63, respectively. A multi-country study found the cost of neuroimaging to vary by country income level and public/private institutions with a range of USD 14 to USD 286.

There is great variability in OOP expenses for neurosurgical Bellwether procedures, but the average cost to the patient did not exceed USD 300. When assessing patient expenditures, attention should be given to average country income, as the cost of a medical expense may be lower in an LMIC but the impact on the patient greater due to lower income. More studies on OOP costs for neurosurgical interventions in LMICs are needed to provide evidence for policy changes geared towards financial risk protection.

In 2015, the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery published their report estimating lack of access to safe and affordable surgical and anesthetic care for 5 billion people worldwide, with an annual deficit of 143 million surgeries to care for those people.1 The global surgical and in particular the global neurosurgical community has risen to address this enormous deficit and increase surgical capacity specifically in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). However, as surgical capacity increases, the cost to the patient must be closely monitored and limited in order to protect the 33 million people who face catastrophic health expenditures each year due to the cost of surgery and anesthesia.1 To do so, catastrophic expenditure, defined as the incurring of health payments higher than the resources of a household (>10% of annual expenditures2 or >40% of non-subsistence expenditure3), and impoverishment due to out-of-pocket (OOP) health payments, defined as healthcare payments that push families below the poverty line (USD 3.10/person/day) or push the impoverished even deeper into poverty,4 are two indicators commonly utilized to track the level of financial protection in health.5 These indicators are crucial as the affordability of surgical and anesthetic care for a hospital or government does not necessarily reflect the affordability for patients.3,6

Even in high-income countries (HICs), catastrophic expenditure is of great concern.7,8,9,10 In the United States, illness and medical bills are one of the leading causes of bankruptcy7, with 22% of Americans skipping medical consultations and 18% not purchasing prescribed medication due to cost8. These problems often disproportionately affect low socioeconomic patients.8

In order to address these issues, we must first determine the financial burden on patients by calculating the OOP costs for their essential care. Recent efforts have collected such data, mostly in HICs on a multitude of diseases such as cancer care in Germany and Italy9,10 and congenital heart disease in the United States11. Research efforts have also extended to LMICs, determining OOP costs for essential obstetric12,13,14 and surgical care15,16,17. However, although essential and emergency neurosurgical care in LMICs has been shown to be relatively inexpensive, costing as much as an appendectomy for some procedures,18 there is little data on OOP costs to patients for these procedures. This study seeks to collate the current literature on OOP costs of Bellwether neurosurgical procedures in LMICs in order to provide a basis for calculations of financial burdens, as well as determine the deficits in the current literature and guide future research efforts.

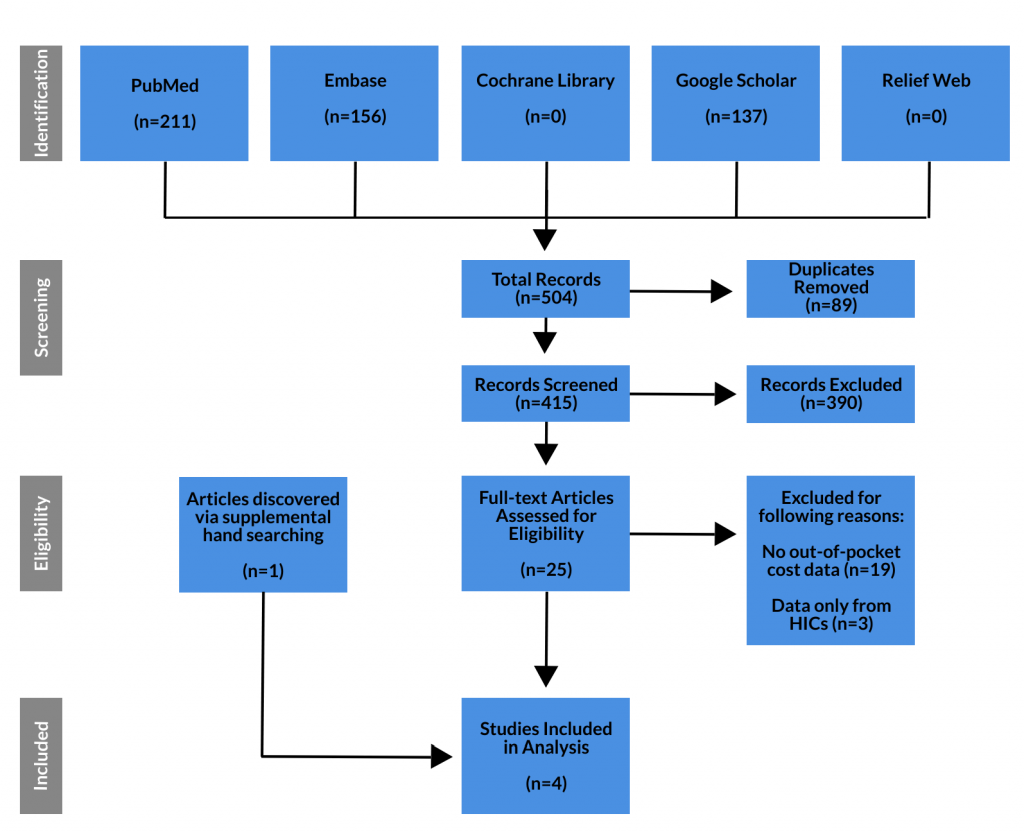

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using MEDLINE/PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar and Relief Web in June 2020 following PRISMA guidelines. The search strategy included title/abstract and controlled vocabulary terms for LMICs, cost and selected neurosurgical procedures, captured from all years. Supplemental hand searching was performed to identify additional records. The complete search strategies, including search terms, are available in the Appendix. The title and abstract screening was performed on all included studies by one author (A.A.). Full text review, inclusion/exclusion determination, and data extraction was performed by four authors (A.A., R.H., A.V., A.B.). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus between the reviewers. Articles were evaluated for whether they contained data on the OOP cost of neurosurgical procedures in LMICs. Included studies had to meet the following criteria: 1) describe OOP costs for patients of selected Bellwether neurosurgical procedures – craniotomy for trauma and abscess evacuation, hydrocephalus treatment, and computed tomography (CT) head imaging, 2) be written in English language, and 3) describe procedures in low, lower-middle, and upper-middle income countries (combined here as low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)) as defined by the World Bank Country and Lending Groups classification.19 Low-income, lower-middle income, upper-middle income, and high-income countries were all defined by the World Bank income classification.19 As there is no consensus description of Bellwether neurosurgical procedures, the definition was extrapolated from the World Bank’s Disease Control Priorities20 and a study detailing Bellwether procedures for pediatric neurosurgery21 to be any essential neurosurgical procedure that is suited for a primary or secondary-level hospital to perform. From these papers, the authors selected a focus on craniotomy for trauma and abscess evacuation, hydrocephalus treatment, and head CT imaging. There was no time frame limitation for publication. Exclusion criteria included studies from HICs and studies on health system costs of procedures. Figure 1 demonstrates the detailed process of excluding articles to get to the final count for data extraction.

Due to study heterogeneity, data was not pooled and further systematic analysis was foregone.

The initial literature search yielded 211, 156, 137, 0, and 0 studies from PubMed, Embase, Google Scholar, Cochrane Library, and Relief Web, respectively. Of these 504 studies, 89 were duplicates, leaving 415 studies that were screened via title and abstract review. 25 studies were determined to require full text review, of which 19 reported no OOP cost data, and three other studies reported data from HICs only. One additional article was found via supplemental hand searching, which did not reference neurosurgery or neurosurgical procedures but referred to surgery for “head injury”, which we took to mean craniotomy for trauma. This left 4 studies that reported data on OOP cost for the neurosurgical Bellwether procedures in LMICs, and were used for data analysis (Table 1).

Amongst the 4 articles which met the relevance criteria, 17 LMICs are represented. The low-income countries (n=8; 47.1%) include Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Haiti, Myanmar, Somaliland, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. The low-middle income countries (n=9; 52.9%) include Bhutan, Ghana, India, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Nigeria, Pakistan, Tunisia, Vietnam, and Zambia. Collectively, the papers were published during the time period of 2015 to 2018, and they involved patient data existing from years 2010 to 2016. Three of the involved studies utilized a survey tool for data collection, while one study produced data based on introduction of a new surgical device. All of the studies investigated medical costs for a variety of healthcare expenditures. The cost of neurologic tests or neurosurgical intervention was common amongst the articles included in our study. Cost analysis pertaining to OOP costs for neurosurgical procedures were included in two articles, which individually presented data from the low-income country Uganda, and the low-middle income country Vietnam.22,23 Cost analysis pertaining to OOP costs for diagnostic imaging was included in one article, which presented data collected from 37 different countries.25

Given the limited number of studies and their heterogeneity, direct comparison of their results was not possible. Instead, we report their results descriptively. The studies differentiated between direct medical expenses (cost of surgery, medication, etc.), direct non-medical expenses (travel, lodging and food) and indirect expenses (lost wages).

At one government hospital in Uganda in 2016, the median direct medical expense for patients undergoing surgery other than cesarean section – of which only 3% were neurosurgical patients – was USD 118.06 with a range of USD 42.17 to USD 320.46. In the same group, the median cost for direct non-medical expenses (transport/food) was USD 84.33.22 The authors in this study did not define the type of neurosurgical procedures performed or where in the range the neurosurgical patients fell, limiting accurate understanding of neurosurgical costs. In a similar study examining hospitalized trauma patients at a single hospital in Vietnam in 2010, head injuries had an average total medical care OOP cost of USD 287.30. As part of that cost, craniotomy for trauma cost USD 63. The authors found three major drivers of OOP cost, all direct medical expenses: cost of surgery, cost of diagnostic tests/examinations, and cost of medications. Non-medical expenses amounted to USD 19.20 for transportation and USD 23.80 for hospital stay.23 These studies do not delineate the cost of implants, however, which is an important consideration specifically in the treatment of hydrocephalus where cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) shunts are commonly utilized. Authors in Tunisia developed an external ventricular drain for temporary shunting of CSF that cost USD 10-20, compared to USD 170-380 for contemporary external ventricular drains in Tunisia.24

One of the studies focused on neuroimaging, for which we report the data on head CT testing given its utility in cases that may require neurosurgical intervention. The study provided data on cost of head CT testing and other neurodiagnostic studies in 2015 from 37 countries encompassing 8 (22%) low-income countries, 7 (19%) lower-middle income countries, 13 (35%) upper-middle income countries, and 9 (24%) high-income countries. The mean OOP cost for head CT imaging differed between country income groups, with high and upper-middle income countries costing more than low and lower-middle income countries (p=0.07), and between public and private institutions, with private institutions costing more than public (p=0.02) (Table 2). The gap in cost between the public and private sector increased for higher income countries, with the mean OOP cost for head CT imaging at private institutions less in low and lower-middle income countries compared to high and upper-middle income countries, and the reverse holding true for public institutions, with the mean cost of head CT imaging greater in low and lower-middle income countries compared to high and upper-middle income countries (Figure 2). In lower-middle income countries, however, the cost of head CT imaging was the same for public and private institutions. It is also important to note that the affordability of CT for patients increased with increasing country income level, with only 10-20% of the population able to afford any neurodiagnostic test at below catastrophic health care expenditure levels in low-income countries, but 80-100% of the population in high-income countries as the relative cost of CT compared to average per capita income decreased to minimal levels (Figure 2).25

Although our review focused on OOP costs in LMICs, we found three articles specific to HICs in our literature search, one of which detailed hospital rather than patient costs. In order to help provide perspective on the differences between HICs and LMICs, we report the results from the two relevant studies here. At a single institution in the United States, craniotomy for hematoma evacuation and CSF diversion procedures had OOP costs of USD 231 and USD 281, respectively.8 These costs were only for the procedures themselves, however, and did not include other medical and non-medical expenses. Another study took this into consideration when looking at OOP costs of hospitalization for shunt failure at a single institution in the United States. The overall cost was USD 419 including transportation, food and lodging, sibling child care, and medical payment costs for patients, but it varied by insurance type.26

One study that arose in our literature search discussed the cost to the hospital to perform neurosurgical procedures in Uganda. They calculated the cost per patient for 12 main neurosurgical procedures, outlined in Table 3. They found that the mean cost of all the procedures was USD 542 (range USD 291 to USD 1220), with craniotomy for subdural/epidural hematoma costing USD 316 and ventriculoperitoneal shunting costing USD 615.84.27 A deeper look into the healthcare system costs in Uganda reveal that on average about 73% of their healthcare financing is supported by out-of-pocket contributions from the patients.28 Using this as the percentage of cost that a patient would have to pay, we can calculate the rough OOP cost of craniotomy for subdural/epidural hematoma evacuation and ventriculoperitoneal shunting to be USD 230.68 and USD 449.56, respectively. However, this is a rough estimate from one hospital and does not include direct non-medical costs or indirect costs for the patient and assumes no profit margin for the hospital.

Although there is limited data on patient OOP costs for neurosurgical Bellwether procedures, some important points are raised by the currently available literature. There is high variability in the reported OOP expenses for patients, varying between countries as well as private and public institutions within a country, but the average cost to the patient was usually not more than USD 300.22,23,25 These costs account for both direct medical and non-medical expenses, including travel to the hospital, lodging and food, which are just as important as direct procedural costs when determining catastrophic and impoverishing expenditures. Implant and consumable costs, specifically to the patient, such as for external ventricular drains and CSF shunt devices, as well as indirect costs such as lost wages are also important to consider. We also found that even though OOP cost is slightly lower in LMICs compared to HICs, the cost relative to patient income is higher with a larger percentage of the population not able to afford these procedures in LMICs, and so country specific calculations are needed in order to ensure reduction in catastrophic expenditures.25 Using Uganda as an example, although user fees for health services in public facilities were abolished in 2001, 73% of their healthcare financing is supported by out-of-pocket contributions from the patients.28 This is an enormous cost to be borne by patients, especially since the adjusted net national income per capita in Uganda is only USD 533 and payment for essential neurosurgical procedures could amount to almost 50% or more of annual income for a patient.29 However, as we advocate for access to affordable neurosurgical care within universal health coverage, we must consider the sustainability of the systems as well, with low to no out-of-pocket payment supplementation placing a high cost burden on healthcare systems of hospitals and countries as well.

As two of the six key indicators for health system strengthening defined by the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery,1 patient financial risk protection is integral to the health and safety of a population. However, even though health information is the backbone of health system development,30 we lack the data necessary to develop health systems that are not only safe and accessible to patients, but affordable and equitable as well. The first step in reducing the financial risk to patients who undergo essential and often life-saving neurosurgical procedures is to determine the costs through studies like the ones included here.

Limitations of this review include the limited number of articles specifically regarding the OOP costs to patients for neurosurgical Bellwether procedures in LMICs. Multiple factors have likely led to this dearth in literature. Although patient financial protection has been a key aspect of health policy,31 data collection on factors affecting patient OOP costs is relatively new.3 In addition, the difficulty in collecting this data is underlined by the multiple cost factors seen in our results – direct medical, direct non-medical, and indirect costs. In LMICs in particular, the underdevelopment of monitoring and evaluations systems makes this even more difficult, and leads to a vicious cycle where lack of accurate health data is both a cause and symptom of underdeveloped health systems.32 Another limitation is that the studies included in our review are heterogeneous – one for “head injury”/craniotomy, one for head CT, one for external ventricular drain implant cost, and one for which neurosurgery was only 3% of cases and not defined.22,23,24,25 Our search criteria were limited to English language journals, which may have missed articles from journals in LMICs written in other languages. However, even if there were more articles on the subject to analyze, there is tremendous variability between countries and even within a country considering health insurance, public vs. private hospitals, and payment methods that reduce the ability to generalize data.

There is a dearth of literature on the out-of-pocket costs for patients undergoing neurosurgical procedures, especially in LMICs. There is a dire need for more research on this subject in order to address the issue of catastrophic expenditures due to the cost of surgery and anesthesia. When collecting such data, researchers should consider cost models that incorporate direct medical expenditures, including implant and consumable costs, direct non-medical expenditures such as transportation, food and lodging costs for patients and their families, and indirect expenditures such as lost income during the patient’s time in the hospital and recovery. Because costs vary amongst countries, each country should have a study of their specific OOP costs for neurosurgical procedures. This data must then be compared to country-specific income levels to inform the development of policies that reduce catastrophic and impoverishing expenditures for patients and make essential neurosurgical procedures accessible and affordable to the entire population, promoting universal neurosurgical care.

Adam Ammar is a Neurosurgical resident at Albert Einstein/Montefiore Medical Center, and a Global Neurosurgery Fellow at the Harvard Medical School Program in Global Surgery and Social Change. He graduated from the Johns Hopkins University in 2010 with a Bachelor of Arts in Neuroscience with a minor in Entrepreneurship & Management, then completed medical school in 2015 at the University of Illinois at Chicago, where he was inducted into Alpha Omega Alpha and the Gold Humanism Honor Society. His research efforts are focused on pediatric and global neurosurgery.

Adam Ammar is a Neurosurgical resident at Albert Einstein/Montefiore Medical Center, and a Global Neurosurgery Fellow at the Harvard Medical School Program in Global Surgery and Social Change. He graduated from the Johns Hopkins University in 2010 with a Bachelor of Arts in Neuroscience with a minor in Entrepreneurship & Management, then completed medical school in 2015 at the University of Illinois at Chicago, where he was inducted into Alpha Omega Alpha and the Gold Humanism Honor Society. His research efforts are focused on pediatric and global neurosurgery.

Medical doctor interested in Global Neurosurgery who needs to contribute to a better future for the underserved.

I am a neurological surgery resident from Malaysia and Master of Public Health degree holder from Harvard Chan School of Public Health. I am the incoming Paul Farmer Research Fellow for the Program of Global Surgery and Social Change (PGSSC). Current interest mainly in Global Neurosurgery, health equity, health system and big data.

I’m a father, a husband and a PGY3 Neurosurgery RMU, Pakistan, Secretariat Member of WFNS GNC.

Dr Myron Rolle is a neurosurgery resident, Global Neurosurgery fellow, Rhodes Scholar, former NFL player and founder of the CARICOM Neurosurgical Initiative.

Dr. Park practiced private neurosurgery for 12 years in the US before spending the next decade teaching neurosurgery in Nepal, Ethiopia, and Cambodia. He then returned to the US to obtain his MPH at the Harvard Chan School of Public Health. He joined the Program in Global Surgery and Social Change in 2016 where he leads the policy and advocacy aspects of global surgery as well as the global neurosurgery initiative.

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()