Miller L, Ellis L. Health disparities in genetic testing for patients receiving government-funded insurance benefits. HPHR. 2021; 30

DOI:10.54111/0001/DD33

Patients receiving public health insurance benefits receive lower-quality, less-reliable care compared to patients with private insurance benefits. This study sought to determine the impact of race and insurance coverage on rates of genetic testing received by patients on government-funded insurance plans in Southeastern Wisconsin.

This study retrospectively reviewed 1,374 genetic testing records from 477 unique patients from January 1, 2015 through June 30, 2017.

The largest number of tests were performed on patients with coverage provided by Medicare (N=512). The highest proportion of tests not fully paid by the primary insurance were performed on patients with Medicaid-EBD (N=272).

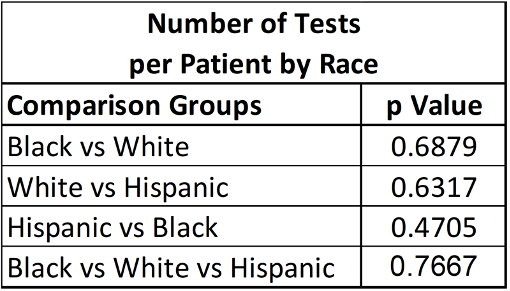

The three most common races represented were Black (N=226), White (N=148), and Hispanic (N=38). The differences in rates of genetic testing procurement by race between Black, White, and Hispanic patients were not statistically significant (p=0.7667). When comparing the rates between individual races, the differences were not statistically significant (p>0.05).

When comparing tests per patient, no specific race received significantly different rates of genetic testing compared to the other races. This suggests that patients who receive public insurance benefits in Wisconsin receive the equal access to genetic testing, regardless of patient race.

Health disparities are defined as “a particular type of health difference that is closely linked with social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantage.”1 Despite efforts to ensure equitable healthcare to all, gaps in care are still evident in today’s population.2 Many disadvantaged individuals qualify for government-funded health care coverage.3 In Wisconsin, those programs are Medicare, Medicaid for the elderly, blind and disabled (Medicaid-EBD), and BadgerCare Plus.

Medicare is federally funded health plan for individuals over the age of 65, some younger individuals with disabilities, and those diagnosed with End-Stage Renal Disease.4 Medicaid is also a federal program, but states retain the right to decide which services are covered. In this study Medicaid-EBD refers to the plan for the elderly, blind or disabled. Eligible persons must be 65 years of age or older, or must be blind or disabled.5

BadgerCare Plus is the standard Medicaid health plan that is offered to all low-income residents between the ages of 0 and 64. This funding is intended to cover individuals who do not yet qualify for Medicare and/or Medicaid-EBD in Wisconsin.6

Despite having primary insurance coverage, some patients require a second insurance provider for supplemental coverage. Independent Care Health Plan (iCare) is a private insurance company located in Milwaukee, Wisconsin that provides supplemental insurance to individuals whose primary insurance is through Medicare or Medicaid. The coverage provided by iCare applies to the costs incurred by patients that their primary insurance does not cover.

Genetic testing is a rapidly developing field within the healthcare industry. A multitude of tests are available, including panels focusing on specific genes as well as sequencing looking for small changes in genetic material. However, genetic testing methodologies are highly complex and require training and expertise, which results in a high cost for testing. In addition, the results of genetic testing are difficult to interpret as not all genetic variants will cause disease and multiple genetic variants can cause the same disease.7 Due to high costs and limited clinical utility for some disease states, insurance providers do not always cover this testing.8

The study sought to determine the impact of race and insurance coverage on rates of genetic testing received by patients on government-funded insurance plans in Southeastern Wisconsin.

This study reviewed all genetic testing records at iCare from January 1, 2015 through June 30, 2017. The types of genetic tests in the study included orders for specific genes and sequencing analysis for unknown single nucleotide polymorphisms. The most commonly performed tests were MTHFR (N=151), analysis of 2-10 single nucleotide polymorphisms of unknown significance (N=119), CFTR (N=100), and BCR-ABL (N=92). The records reviewed included 1,374 genetic tests performed on 477 unique patients, consisting of 138 males and 339 females.

The population of patients receiving genetic testing was broken down by race and type of insurance coverage: Medicare, Medicaid-EBD, BadgerCare Plus, FCP SNP (Medicare plus supplemental coverage), and FCP SSI (Medicaid-EBD plus supplemental coverage). Further analysis was performed on the genetic tests in each insurance category to elucidate the impact of each insurance on how the testing was paid for and the impact of race on rates of testing. Statistical significance of the rates of testing between the racial sub-populations was performed using Welch’s analysis of variance and t-test analysis.

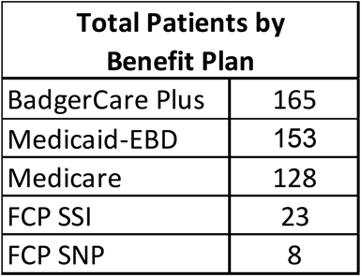

The 477 patients included in this study were spread across the five insurance plans. Most patients had coverage provided by BadgerCare Plus, Medicaid-EBD, and Medicare (Table 1).

A total of 1,374 genetic tests were performed on iCare patients. Out of the tests requested, 745 were paid in full the by patient’s primary insurance plan. The remaining 629 required supplemental reimbursement from the patient’s coverage provided by iCare.

The number of genetic tests received by patients in each type of benefit plan varied. Patients who are covered under Medicare received the highest number of genetic tests with the lowest number of non-covered tests (Figure 1). Patients covered by Medicaid-EBD received the second highest number of total genetic tests with the highest number of tests not covered. Those covered by BadgerCare Plus received a lower number of genetic tests than the previous two plans and also had a high proportion of tests not covered fully by their primary insurance plan. The patients covered by Medicare and Medicaid-EBD who also carry supplemental insurance (FCP SSI and FCP SNP, respectively) received the lowest rates of genetic testing.

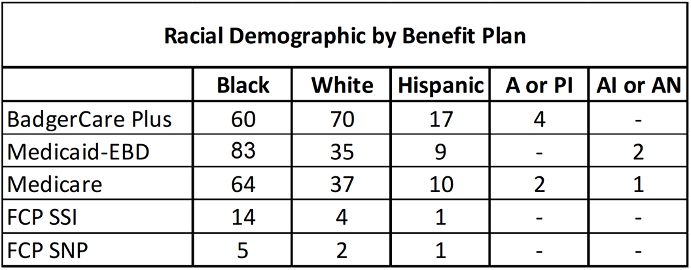

The three most common races represented were Black, White, and Hispanic (Table 2). Black patients were the most common race represented in both Medicare and Medicaid-EBD, and the second most common in BadgerCare Plus. White patients were the second most common patients represented in Medicare and Medicaid-EBD, and were the most common race represented in BadgerCare Plus. Hispanic patients were the third most represented race in Medicare, Medicaid-EBD, and BadgerCare Plus. Patients without a defined race, noted as “Not Provided” or “Other” were excluded from analysis.

The races that received the most genetic testing were Black, White, and Hispanic, which corresponded with the number of patients represented in each racial sub-population (Figure 2).

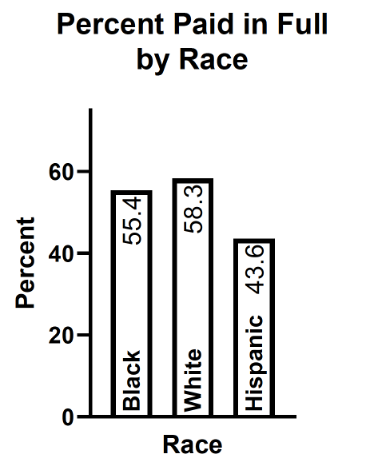

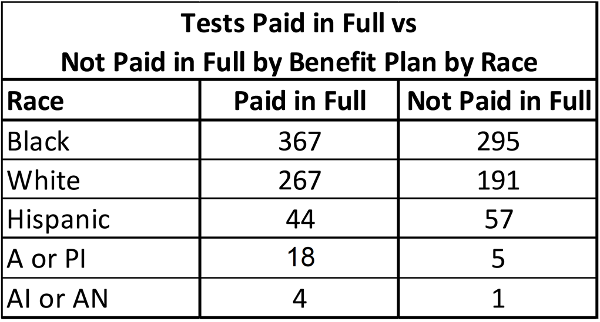

When comparing the genetic tests that were paid in full by the primary insurance provider versus those that needed supplemental reimbursement from iCare, Hispanic patients had the highest rate of tests not paid in full (Figure 3 and Table 3). The subpopulations of Black and White patients each had over half of the testing paid in full by the benefit plan.

The differences in rates of genetic testing procurement by race between White, Black, and Hispanic patients were not statistically significant when calculated using analysis of variance (p=0.7667). The subpopulations of American Indian or Alaskan Native and Asian or Pacific Islander were excluded due to the very small population sizes. When comparing the rates between individual races, the rate of genetic testing was not statistically significant using unpaired t-test analysis (Table 4).

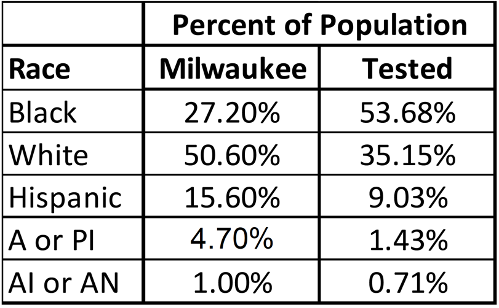

When comparing the racial breakdown of the iCare population to the racial breakdown of the population in Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, Black patients made up a higher proportion of the testing population compared to the general population while all other races made up lower proportions of the testing population compared to the general population (Table 5).

As of 2017, the Milwaukee demographics were as follows9:

This study sought to determine if the racial disparities seen in healthcare as a whole translated specifically to the provision of genetic testing in a specific population of patients in Southeastern Wisconsin. Over the 2.5 years covered by this study, a total of 1,374 genetic tests were performed on patients for a variety of genetic conditions. The majority of the testing was performed on patients receiving insurance coverage through Medicare, Medicaid-EBD, and BadgerCare Plus. The largest number of tests were performed on patients with coverage provided by Medicare (37.3%). The highest proportion of tests not fully paid by the primary insurance were performed on patients with Medicaid-EBD (64.0%). When the tests not fully paid for by the benefit plan were analyzed by race, Hispanic patients had the highest rate of needing supplemental coverage from iCare. Overall, the results of the testing did not reflect the expected breakdowns for the insurance coverage and race as expected from Milwaukee’s population.

Patients who received genetic testing with only Medicare coverage received the highest amount of genetic testing (37.3%). This could likely be due to age of the patients in Medicare as patients over the age of 65 are more likely than younger patients to have chronic diseases in need of diagnosis.10 It has also been well-documented that patients ages 65-84 disproportionately spend a greater amount of healthcare than patients in other age groups.11 Patients receiving coverage through Medicare also had the lowest proportion of test payment needing supplemental coverage by iCare (27.1%). Genetic testing coverage by Medicare is limited to specific cancer diagnoses associated with known mutations such as BRCA1 for breast cancer and MSH2 and MSH6 for Lynch Syndrome.12 However, this coverage is more expansive than Medicaid programs.13

Patients receiving insurance coverage through Medicaid-EBD who required genetic testing received the second highest number of genetic tests performed during the study period (30.9%). Sixty-four percent of the testing was not paid in full by Medicaid-EBD, requiring supplemental coverage by iCare. Patients with coverage through BadgerCare Plus received the third largest number of genetic tests during the study period with over half of testing (55.1%) requiring supplemental coverage from iCare. Wisconsin Medicaid programs (including Medcaid-EBD and BadgerCare Plus in this study) require a case-by-case approval for genetic testing and many specific tests require prior authorization. Additionally, the administrator of Medicaid plans in Wisconsin has a maximum fee schedule that is eligible for reimbursement, regardless of the actual cost of testing.14

The type of genetic testing required by patients in this study likely contributed to the reimbursement by the different health plans reviewed. Genetic testing can be performed using single gene analysis (CFTR), panel testing (colon cancer screens), or by sequencing larger parts of the genome for variants of unknown significance.15 The cost of the testing depends on the complexity of the analytical method and number of results that will be provided when testing is complete, and can range from a few hundred dollars to a few thousand. Because this study encompassed all testing records, it is likely that the more complex testing methods with higher costs resulted in higher rates of non-reimbursement by the primary health plan. Regardless of the testing type, Hispanic patients had the lowest rate of testing coverage by the benefit plan (43.6%) with White patients having the highest number of tests paid in full (58.3%). This difference in coverage could be due to a number of factors including the tests performed, the patient’s clinical presentation, and indications for testing.

Differences in incidence of the disease states tested for also likely impacted the small differences rates of genetic testing by race. For example, CFTR variants cause cystic fibrosis more often in Caucasian populations, and mutations in G6PD causing deficiencies in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase are more common in Black and Mediterranean populations, while BRCA1/2 mutations in breast cancer and BCR-ABL mutations in leukemia can be found throughout the general population, regardless of race. As reimbursement for testing by insurance providers is based upon available data indicating clinical significance, the incidence of disease, and indications for testing based upon available data, these factors likely influenced the rate of testing and reimbursement for the racial subpopulations included in this study.

The greater representation of Black patients in the study population compared to the general population in Milwaukee, Wisconsin is reflective of these patients having higher poverty rates and poorer health outcomes than other races within the state.16 These patients are more likely to be covered by government-funded benefits, and their health status potentially causes them to need supplemental coverage for expenses.

In context of the literature, this study provides data to answer a previously unknown question. While it is widely accepted that Black and Hispanic patients are much more likely to have government-funded health insurance compared to White patients, and that patients on government-funded health benefits face disparities that prevent them from accessing more expensive treatments, this study demonstrated that despite the disparities when compared to private insurance, these populations are not further disadvantaged by race when accessing genetic testing when compared to each other.17 However, barriers to genetic testing do exist for patients in ethnic minorities compared to White patients. Studies have shown that minority patients are less likely to be referred for genetic testing compared to White patients.18,19 Some of the barriers could include lack of knowledge about testing for both patients and providers and distrust of the medical system stemming from past prejudices in addition to the differences in insurance coverage.18

System barriers could also be compounding on the differences in insurance coverage between private and government-funded benefits. As genomic medicine is still a rapidly developing field, the nation’s billing platforms have not been able to keep pace with the changes. In 2019, fewer than 200 billing codes existed for over 70,000 genetic tests.20 This makes it impossible for insurers to bill for genetic tests in a standardized fashion. Additionally, with the lack of data on clinical utility and necessity as these tests hit the market, it can be difficult for insurers to know which tests should be covered under what clinical circumstances.20 As this industry continues to evolve, more data about testing will be needed to ensure insurers provide proper reimbursement for patients that require genetic results to direct their care.

While health disparities for disadvantaged populations have been documented for patients receiving government-funded benefits compared to private insurance, within the population analyzed, there was no significant difference between the number of genetic tests received by patients of different races, regardless of which government-funded insurance plan they held. When comparing tests per patient, no specific race received significantly different rates of genetic testing compared to the other races. This suggests that patients who receive public insurance benefits receive equal access to genetic testing, regardless of race. However, this suggestion is limited by the specific demographics of this population as this sample is a small subset of patients from Southeastern Wisconsin. The variability of sample size between the racial subpopulations, while accounted for in the statistical analysis, limits the applicability of this study to a larger population. Additional studies using different populations are needed to determine the applicability of this study’s findings in other contexts. Further research is also needed to quantify the difference in procurement of genetic testing between private and public insurance, and determine its significance in the context of known health disparities.

The primary author would like to thank Independent Care Health Plan for supplying the study data, as well as the Wisconsin Medical Society Foundation and the Waukesha County Medical Society for providing the fellowship funding to make this experience possible.

Lauren J. Miller is a 3rd year medical student at the Medical College of Wisconsin and aspiring pathologist. Her research interests include quality improvement, medical genetics, and medical education.

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()