Begum F, Dodson B, Srinivasan A. Community health assessment of Muslim women at an East Harlem Islamic Center. HPHR. 2021; 30.

DOI:10.54111/0001/DD13

Create a health profile of Muslim women in East Harlem.

Surveys at the Islamic Cultural Center in East Harlem, NY, during Ramadan in 2016 and 2017. Questions pertained to demographics, health insurance, health status, preventive care, women’s health services, and perceived health issues. Chi-square analysis of principal outcomes was compared with representative populations.

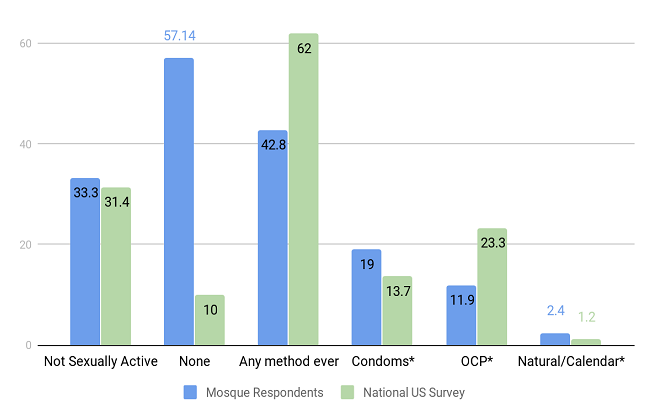

Surveys completed by 79 women with an average age of 32 around New York City. Racial composition: 40.5% black, 36.14% Asian, 17.72% Middle Eastern, and 6.32% Hispanic. Eighty-four percent reported “good” or “excellent” health. Eighty-two percent had health insurance; 50.76% public insurance. Seventy-six percent had a physical exam and 70.88% had seen in a dentist in the past year. In the past year, 34% had a cervical cancer screening in the previous year and 45% received a mammogram, similar to the utilization rate for control population. Of sexually active women, 57.14% used no contraception, 19.04% used condoms, and 11.9% used hormonal birth control. All these measures were significantly different than the control population.

Worshippers at the Islamic Cultural Center are unique and diverse. This preliminary assessment contributes to the small body of existing work and creates a foundation for future research with similar populations.

There are over 3 million Muslims in the United States and The Pew Research Center estimates this number will double by the year 2050.20 Approximately 400,000 to 800,000 people of the New York City metropolitan area are Muslims.6 Despite this significant number, the

healthcare needs and self-assessments of Islamic populations are rarely published, creating a blind spot in data-based healthcare policies. National healthcare services and databases don’t ask about religious affiliations, which likely influence healthcare practices and decisions, hence compromising the quality of care and opportunities to address healthcare needs. Therefore as an attempt to help eliminate this blind spot, this study explores the health needs of Muslim women worshipping at the Islamic Cultural Center in East Harlem, New York (ICCNY).

In 2015, the University of Michigan conducted a study with four Muslim community organizations in Southeast Michigan. They found that participants had a God-centric view of healing, which can be accomplished by direct religious means, i.e. praying and reciting the Quran, and through indirect agents such as doctors, family, friends, and Imams (Islamic leaders). Participants also stated they want physicians to be more religiously competent and sensitive towards their beliefs and practices.2

When looking for research on the health profile of Muslim groups from other countries, the 2001 UK census found that Muslims, compared with other groups in the UK, have the highest rate of reported ill health and disability. It is important to note that the ethnic makeup of Muslims in the UK are largely of Asian descent, while more Muslims in the US are of African descent. Muslims in the US also have a higher overall socioeconomic status than Muslims in the UK.18

Despite the racial variation of Muslims, there are unique health concerns general to the Muslim population, including risks of infectious diseases during Hajj (annual pilgrimage to Mecca). Additionally, health professionals should counsel patients about fasting during Ramadan, especially those with chronic illnesses or pediatric patients. Doctors should be aware of the occurrence of female genital mutilation, a practice seen in some African-Muslim populations that may need to be reported.18 Most Muslim patients are more comfortable with same-sex practitioners, with as little unveiling as possible,26 and prefer examination with family members present.16 It is important to note that mental illness is often stigmatized, and Muslims may prefer private reflection and religious strategies for managing depression and symptoms of schizophrenia.18 This could impact how respondents answer questions about mental health issues in their community.

Health profiles of Arab Americans, 50% being Muslims,11 have shown a significantly greater mortality due to diabetes, cardiac disease, and cerebrovascular disease than non-Hispanic white men.12 Similarly, a study conducted in 2002 found Arab Americans in Southeast Michigan have more risk factors for coronary heart disease including higher blood pressure, cholesterol, BMI, and smoking rates, and decreased HDL levels.14 Arab-American men have a higher prevalence of smoking (20–30%), compared to 14 % of all Americans, and a lower quitting rate than the general U.S. adult male population.13,15

When looking at the East Harlem population, it is a population of 108,100 with 55% Hispanics and 33% Blacks. The leading causes of death in this area are, in the following order: heart disease, cancer, diabetes, lower respiratory tract infection, HIV, stroke, hypertension, drug-related issues, and Alzheimer disease. Ten percent of all live-births in the area are preterm. In 2015, the percentage of people who reported their own health status as excellent, good, or very good was 70% in East Harlem, compared with 78% in NYC. Approximately 19% of East Harlem residents are smokers, compared to 15% of NYC residents. Thirty-three percent of East Harlem residents are obese and 13% have diabetes, while NYC residents have rates of 24% and 10%, respectively. East Harlem ranks fifth in highest number of avoidable hospitalizations due to diabetes. This was a major driver for NYC Health + Hospitals at Metropolitan Hospital (NYCH&H/Metropolitan Hospital) to establish a diabetes center of excellence. There is a significantly greater percentage of alcohol and drug-related hospitalizations than in other NYC areas. Access to healthcare is also an issue in East Harlem, since 24% do not have health insurance, versus 20% in NYC overall. There is also a greater percentage of new HIV diagnoses in the East Harlem area than in NYC as a whole (46.1 per 100,000 v. 30.4 per 100,000). East Harlem has more than twice the percentage of psychiatric hospitalizations compared to NYC and the fifth highest rate of avoidable asthma hospitalizations. It also has a greater percentage of stroke incidents than NYC as a whole, with hypertension as a leading risk factor.17,19 This data points to some of the health concerns of the East Harlem community, however there are no surveys or hospital data reflecting the health concerns of the a Muslim community in NYC.

After initiating conversation with the Imam, securing the Mosque’s cooperation, and recognizing the community’s interest in our health assessment initiative, we conducted voluntary in-person anonymous surveys of women at ICCNY aged 18 to 65 at the mosque during the Islamic month of Ramadan for two consecutive years (June-July of 2016 and 2017). This was convenience sampling. The surveys were presented in English and translated into Bengali as necessary (since one of the researchers speaks Bengali). The surveys averaged 5-8 minutes and were completed on electronic devices provided by NYCH&H/Metropolitan Hospital. The Institutional Review Board at the New York Medical College approved this study, and all subjects provided oral consent.

Our survey (appendix 1) was created using the NYCH&H Community Health Needs Survey, provided by Metropolitan Hospital along with the corresponding 2016 patient survey results. Metropolitan Hospital is in close proximity to the ICCNY, therefore results from the 2016 survey provided a comparison to the needs of a Muslim population in a similar geographic area. It is important to note that worshippers at the ICCNY come from various areas and are not limited to the service area of NYCH&H/Metropolitan Hospital. Data acquired from our survey was compared to national, state, and city data.

The survey questions assessed health concerns, services utilized, and the healthcare status of women in the Muslim community. Respondents were asked about their demographics (age, residential zip codes, race, and language), perception of health, health insurance, health care services received, and family planning methods. Women were asked to rate the severity of health issues in their communities by selecting 0, 1, 2, 3 or ‘Not Sure’. Health issues addressed include hypertension, obesity, diabetes, cancer, asthma, mental illness, dementia, premature births, HIV/STDs, alcohol/drug abuse, and smoking.

Only women above the age of 21 and 40 were considered for the Pap smear and mammogram questions, respectively.7,3

We conducted a Chi-square test to determine significance compared with the results of the NYCH&H/Metropolitan community needs assessment.

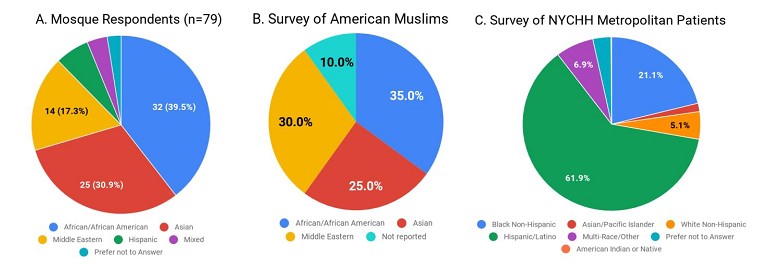

There were 79 total survey responses: 65 from 2017 and 14 from 2016. The average and median ages of respondents were 32.14 and 30, respectively. Sampling included residents from NYC (n=74), Long Island (n=2), New York state outside of NYC (n=1), and eastern New Jersey (n=2). Women from the ICCNY have a similar race distribution as American Muslims; these distributions are different from patients at Metropolitan Hospital (Figure 1).16

The majority of respondents spoke English (56.96%, n=45), 20.25% spoke Arabic (n=16), 15.18% spoke Bengali (n=12), 10.12% spoke Urdu (n=8), 8.86% spoke French (n=7), and 5.06% spoke Spanish (n=4).

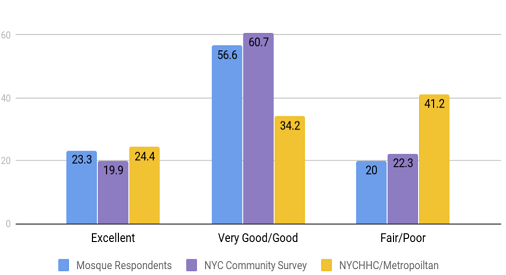

Self-reported health status of women from ICCNY (Figure 2) was statistically different (p=2.806×10-6) from the NYCH&H/Metropolitan community needs assessment, and was not different from the NYC community health survey (p=0.57).

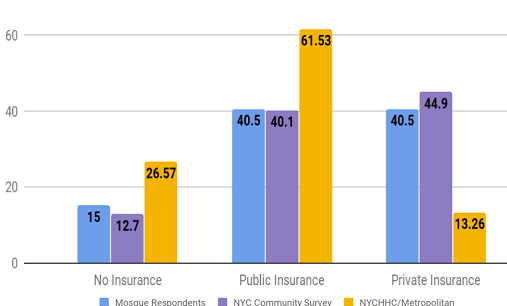

Our data was statistically different from the NYCH&H/Metropolitan community needs assessment (p=1.562×10-15), where more of the respondents used public insurance, while not statistically different from NYC community health survey (p=0.653) (Figure 3).

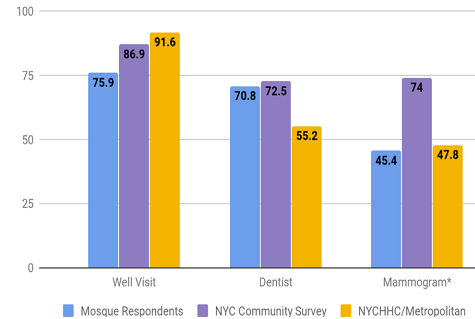

Women’s usage of preventive health services was statistically different from the NYCH&H/Metropolitan community needs assessment (p=0.0078) (Figure 4) but not different from the NYC women’s data (p=0.231).

When asked about hospital visits, 48 of 79 (60.7%) respondents reported using an emergency department for medical services and 40 (50.6%) reported seeking primary care health services in a hospital. In the NYCH&H/Metropolitan survey, 62 out of 143 people responded that they had visited the ER in the past 12 months (43.35%).

Ten (45.45%) out of 22 respondents (over age 40) indicated that they had a mammogram in the past year. A community health survey conducted in NYC in 2015 found that 74% of women over 40 years of age had a mammogram performed in the past one year. In NYCH&H/Metropolitan

Hospital’s 2016 Pledge Report, it was found that 47.86% of patients fulfilled their mammogram orders (Figure 4).

Contraceptive use among women at the mosque differed significantly compared with the Guttmacher Institute’s national data (p=4.5893×10-28) (Figure 5).

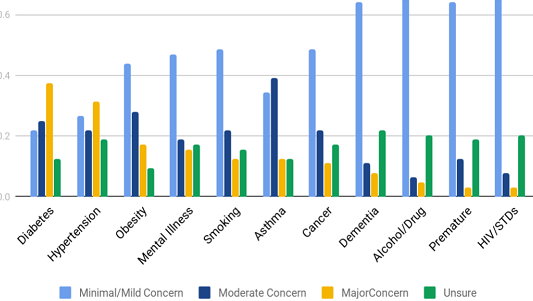

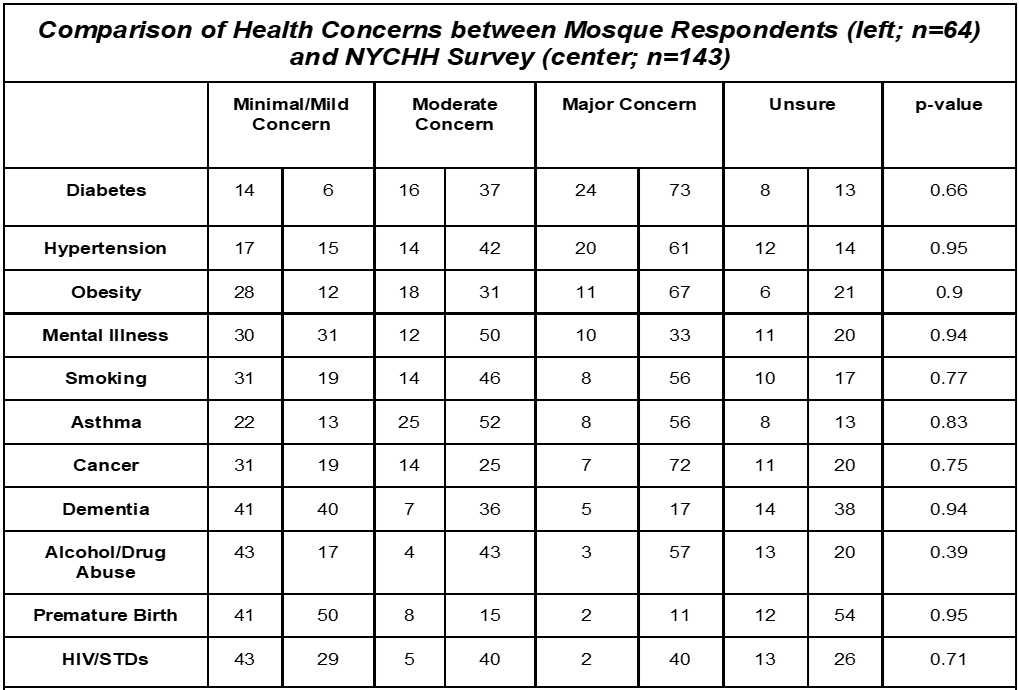

Sixty-four women ranked their health concerns. This data was compared to that of the NYCH&H/Metropolitan Community Needs Assessment. The p-values are depicted in Table 1. After accounting for the rank of each health concern, there was no statistical difference (p>0.01) for any of the variables (Figure 6).

NYCH&H is a large public healthcare system, serving as a safety net provider for the NYC population via 11 acute care hospitals. Despite the size and diversity of the population treated, there is no data addressing care towards the Muslim population it serves. These survey results will create a foundation for future research in this area and help establish improved health outreach programs.

The racial demographics of our study population were similar to that of Muslims nationally.16 Worshippers in East Harlem were 40.5% African/African American, 36.14% Asian, and 17.72% Middle Eastern. This was different from the racial profile of patients at Metropolitan Hospital where 61.9% of patients were Hispanic/Latino and 21.1% were black.1 One explanation for the difference is the wide geographic distribution of attendants of the Mosque, compared with members of the East Harlem community, specifically.

Self-reported health status was significantly different (p=2.806×10-6) from the NYCH&H/Metropolitan community needs assessment.1 A majority of women in the mosque consider themselves in “good” or “excellent” health, similar to the NYC community health survey (p=0.57).9 Health coverage of our respondents was similar to that from the NYC community health survey, but differed from the NYCH&H/Metropolitan community needs assessment where the majority of patients used public insurance. (p=1.562×10-15).1 These results indicate our sample is representative of NYC residents overall, but not of East Harlem.

Use of preventive healthcare over the past year was statistically different from the NYCH&H/Metropolitan community needs assessment (p=0.00782), but not different from the NYC community health survey. Data from the mosque shows 75.94% of women had a physical exam, the NYC community health survey found 86.9% had a well-visit with their PCP, and the NYCH&H/Metropolitan community needs assessment found 91.6% had seen their regular doctor.1 In comparing dental visits in the past 12 months, 70.88% of mosque respondents said they visited a dentist, compared with 72.5% from the NYC community health survey and 55% from the NYCH&H/Metropolitan community needs assessment.1 Visits to the emergency room in the past year were reported by 60.7% of our respondents, while only 43.35% of NYCH&H/Metropolitan respondents had visited this ER.1

Both the East Harlem population as a whole and the mosque population surveyed are generally young; however, the East Harlem population seems to use more preventative care services. Our study population may not see value in visiting a physician unless they are sick, as compared to the population of East Harlem who value well-visits.8,23 This could account for the difference in both the ER visits and the well-visits with primary care physicians.

In the previous year, 33% of women received a cervical cancer screening and 45% of women over 40 received a mammogram. This varies from the NYC community health survey in which 80% of surveyed women had a cervical cancer screening in the past three years and 74% of women over 40 had a mammogram performed that year.9 NYCH&H/Metropolitan Hospital’s 2016 pledge report found 47.86% of women received a mammogram, which more closely follows our data.1 This indicates that could be a geographic reason for the lower rate of mammograms, including less access to facilities in East Harlem or difficulty in scheduling appointments. There could also be cultural and socioeconomic reasons behind the low utilization of mammography services; unfortunately, the socioeconomic status of our respondent population was not explored in our survey. A recent study at the University of Chicago found several “barriers” among Muslim women that prevent them from getting mammograms, including the belief that God controls disease and a desire for modesty. The study found mosque-based intervention can increase the intention to receive mammograms. Prior to the intervention in this study, 58 Muslim women had not obtained a mammogram within the preceding two years. At the one year post-intervention follow up, 22 of the 58 participants had gotten a mammogram.4,25 Our cervical cancer screening results may be skewed from the NYC community health survey because our question specified screenings in the past 12 months, which is inconsistent with guidelines recommending screening every three years.5

The use of contraception among our study population was significantly different from national data (p=4.5893×10-28); NYC data was not available for comparison. Our study found 57.14% of sexually active women do not use any form of birth control and 33.3% are not sexually active. Of women using contraception, 19% use condoms and 11.9% use hormonal birth control. The women in our survey were an average of 30 years old, while the median age of women in US, according to the US Census Bureau in 2010, is 38.5 years.27 Similarly, the Pew Research Center’s Religion and Public Life Project found that 44% of Muslims in the United States are aged 18-29 and 37% aged 30-49.29 This high proportion of practicing Muslims in the younger age group could be one reason why our data was not representative of the national population regarding contraception. This same study also found that 64% of American Muslims consider religion “very important.”29 This could explain the proportion of our study population who is not sexually active. Additionally, religiosity could account for the lower use of contraception since sexual intercourse is often considered for conception only.

We found no statistical difference between perceived health problems of our study population and the NYCH&H/Metropolitan community needs assessment (p>0.05). This was expected, but we were surprised by the “minimal concern” reported by our sample regarding smoking, alcohol use (67.18%), and mental health issues (46.87%). Muslim Arab-Americans experienced greater stress correlated with depression compared to their Christian counterparts.4 Therefore, we expected our sample to report greater concern regarding mental illness. One explanation for this difference is that our survey respondents may not consider stress or acculturation-related depression to be mental illness. Future studies could clarify stressors to better capture their experiences.

Regarding smoking, the percentage indicating “minimal concern” was surprising because of the high prevalence of smoking among Arab-American men.13 One explanation is the Hawthorne effect, in which participants change their behavior or report differently, because they are being observed. In this study, respondents may not have wanted to show the Muslim community in a negative light and therefore reported less concern than they really felt for certain health issues.

As this study collected numerous parameters, there are limitations to these results and analyses. The biggest limitation is the sampling bias, since we were limited to women comfortable speaking to us and using the electronic survey. Our sample was younger than average and most participants spoke English fluently.

A national study would provide valuable information regarding similarities among Muslims overall, and would clarify any data points attributed solely to geography. It would be interesting to study the religious makeup of East Harlem residents to explore the significant differences between our study and the NYCH&H/Metropolitan community needs assessment. A comparison between male and female Muslims would also be illuminating. We encourage further study of this population, as it would enable institutions to develop health and outreach programs specific for the concerns of Muslims in NYC.

1) What is your zipcode or borough?

2) How old are you?

3) What is your race/ethnicity?

4) What language(s) do you speak in your household?

5) In general, how is your health? :

6) What type of health insurance do you have?

7) Where do you regularly receive health care?

8) Which of the following services have you received in the past 12 months. Select all that apply.

9) Do you have a women’s health doctor (gynecologist) ?

10) Do you perform self-breast exams (checking for lumps, etc)

11) Which of the following family planning services do you use. Select all that apply.

12) Do you visit a spiritual, religious, or cultural healer for your medical needs (imam, etc)?

13) Please RATE each of the following health issues based on how serious and/or widespread they are in YOUR MUSLIM COMMUNITY: Where 1 is not so serious and 3 is very serious (options: Unsure, Not a problem, 1, 2, 3).

17) What services have you used at any hospital? Select all that apply

19) Does your community have any other health concerns or are there any services that would help your community ? __________________________________________

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()