Goodman J. The ethics of crisis. HPHR. 2021; 28.

DOI:10.54111/0001/bb12

The harvest has passed, the summer has ended, and we have not been rescued. Over the breaking of my People’s Daughter I am broken, I plunge in gloom, desolation has gripped me. Is there no balm in Gilead, is there no healer there? For why has no mending come to my People’s Daughter?"

Jeremiah 8: 20-22 Tweet

Our country has experienced an unprecedented crisis during the year 2020 caused by a pandemic that has already killed more than 550,000 Americans as of this writing (March 2021). All estimates indicate that many more thousands will die before this public health crisis can be brought under control in the United States.

During times of crisis, citizens are properly asked to perform public services that might be unimaginable in ordinary times, and it is also appropriate during crises to require our leaders to demonstrate real character. In trying to understand these tragic events, I will compare our early failures and more recent successes during the pandemic with earlier crises faced by the United States and France during the Korean War and the Second World War that involve my family’s own experiences and those of the late historian Professor Marc Bloch.

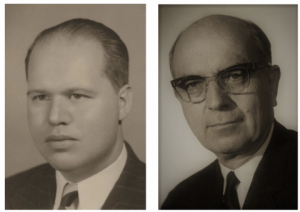

This country’s successful responses to earlier epidemics, including its creation of the Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) in 1951, are examples of how addressing crises competently can lead to positive outcomes for current and future generations. It is sad that my father did not live long enough to join with over 1,000 of his colleagues at the EIS who in May 2020 published an open letter stating that “The absence of national leadership on COVID-19 is unprecedented and dangerous.”2 It was heartening to see that three of the signatories to this letter were from my father’s class of 1951, the first class of the EIS, including his good friend Dr. Jeremiah Barondess. I am also sure that my father would have been encouraged by the recent positive steps taken in 2021 by senior political and public health leaders in our nation’s efforts to address the pandemic

My late father, Dr. Melvin Goodman, was attending the City College of New York (CCNY) when the Second World War began for the United States during December 1941. He was taking pre-medical courses and had completed his first two years of college when he enlisted as a soldier in the U.S. Army in October 1942. Following basic training, he was tested for and accepted into a program that existed only during the Second World War – the Army Specialized Training Program or ASTP. It was created to accelerate training for future doctors, engineers, and linguists that the Army anticipated might be needed in the event of a protracted war.

When my father entered the ASTP, he was sent back to CCNY by the Army to complete additional pre-medical course work. Once he finished these ASTP courses, he was assigned by the Army to attend Cornell Medical College (now known as the Weill Cornell Medical College) where the ASTP had reserved places for ASTP soldiers like my father. Since he had not completed his degree work at CCNY, he attended and graduated from medical school, and received his license as a medical doctor (M.D.), without having received an undergraduate diploma.3

After graduation, my father took his internship in New York City and was beginning to think about a residency program when the Korean War broke out in 1950. Because my father had attended medical school under the Army’s ASTP program through March 1946, and subsequently under the G.I. Bill, he was expecting to re-enter military service as a doctor. At this time, he was recruited by Dr. Alexander Langmuir to join a new organization, the EIS, at the Communicable Disease Center in Atlanta (now known as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or CDC). During January 1951, my father was appointed an Assistant Surgeon in the United States Public Health Service (of which the CDC and EIS are part), and he took immense pride in having served in the first class of the EIS (1951). EIS officers are commonly called our nation’s “disease detectives.”

As part of his service with the EIS, and following his training in Atlanta, he was first assigned to the NY State Department of Health in Albany, NY (July 1951 to July 1952) and subsequently to the NY State Mental Health Commission in Syracuse, NY. It was during this second EIS posting (July 1952 to July 1953) that my father began work on his best-known article4 dealing with mental health, and specifically the alarming and increasing incidence of what we now call developmental disabilities. His findings are still significant to the present day.5

After leaving the EIS in 1953, my father completed his prevalence study for the NY State Mental Health Commission during 1954, and then began a residency program in psychiatry at the Yale University School of Medicine and Grace-New Haven Hospital where he trained with Dr. Frederick Redlich.

The EIS was born during the Korean War conflict6 and was created in response to the fear of possible chemical and biological warfare that could have been directed against the United States by foreign foes. The urgency arising from its wartime genesis remained part of the special culture of the EIS for many decades. My father’s own sense of pride in the EIS was inculcated by the first leader of the EIS, the late Dr. Alexander Langmuir, the first Chief Epidemiologist of the CDC, and one of my father’s lifelong heroes.

As an example of the remarkable ability of talented individuals like my father and his colleagues in the EIS to perform outstanding service during a crisis when they are inspired by true leaders like Dr. Langmuir, and when they are given the opportunity to work without undue interference, at the end of this article I offer a partial summary of my father’s extraordinary efforts to battle various epidemics (including outbreaks of poliomyelitis) during a two year period in the early 1950s while he was still a young doctor in his late twenties (see below).

I note that my father’s efforts were not unique, but rather were typical of the EIS officers led and trained by Dr. Langmuir and his successors, and I hope my father’s example will inspire the talented young men and women working in public health today. The men and women who responded to our nation’s call in the 1950s to help found the EIS were engaged in acts of public beneficence (one of the four key principles of bioethics) towards our country. Dr. Langmuir instilled in all his EIS officers what Professor Bloch calls the spirit of adventure to pursue noble ends, and I can still remember my father’s professional and personal satisfaction in having undertaken this difficult work.

The founding of the EIS during a crisis, the Korean War, and the important work it has performed for the United States over many decades, is a good example of how our leaders and citizens should respond during crises. The following critique by Professor Bloch describes how we should not respond to a crisis, and in his case study he analyzed the initial unsuccessful French response to its invasion by Germany during the Second World War.

Written a few months after the military defeat of France by Germany in 1940, “Strange Defeat”7 by Professor Marc Bloch attempts to make sense of a crisis that seemed unlikely to many people in France just prior to the start of the Second World War. Professor Bloch was a soldier in the French army in both the First and Second World Wars, but he was also a great historian and a founder of the Annales School of history and sociology. After France’s defeat, he joined the French resistance and was ultimately captured, tortured, and executed by the Gestapo on June 16, 1944, ten days after the Free French forces had joined with twelve other Allied nations in the Normandy invasions on D-Day.

The Annales School encouraged use of social scientific methods by historians in addition to the traditional emphasis placed on political and diplomatic studies. Professor Bloch argued that all levels of society should be taken into consideration when looking at major historical events, and he emphasized the collective nature of what this school called “mentalities” (referring to the ways in which ordinary people think and interact with the world.) His work on the Second World War therefore looks at the roles of both great generals and regular soldiers in trying to understand the crisis caused by the German invasion of France.

Professor Bloch begins his case study with a harsh condemnation of France’s military leaders at the start of the Second World War: “Whatever the deep-seated causes of the disaster may have been, the immediate occasion . . . was the utter incompetence of the High Command.”8 It is hard not to echo similar sentiments when considering the early efforts during 2020 of our own country’s leaders in response to the COVID epidemic, which represented a failure of nonmaleficence.

As an example of this failure, he describes a decorated senior officer from the war of 1914 who went to pieces when faced with the new and unexpected requirements of 1940: “Weighed down, I do not doubt, by years spent in office work and conditioned by a purely academic training, this regular soldier lost every quality of leadership — and of the self-control and ruthlessness which the word implies.”9 The problem of allowing uninspired but agreeable and submissive individuals, who thrive in all large corporations and government organizations during ordinary times, to lead our nation during a period of crisis became evident almost immediately in the 2020 COVID crisis.

One of the reasons for the failure of leaders to act swiftly in a crisis is the lassitude that can arise during ordinary times. Professor Bloch writes that this was evident at the start of the invasion of France: “All through that long period of waiting which wrought such havoc in our armies, the peace-time habits of neatness and order, of which we were so proud, had the effect of slowing down the tempo of our lives.”10 A similar sense of complacency was evident at the start of the COVID crisis in 2020 when false hopes that the pandemic would go away were repeated openly and often by our senior leaders. And what a difference having realistic discussions about the pandemic have made to improving the public morale during the recent months of 2021. This is an example of the benefit of the principle of autonomy – truth is often a powerful remedy.

In contrast with these poor leaders, Professor Bloch notes that some true leaders naturally emerge during times of crisis: “It is one of the privileges of the true man of action that, when the critical moment comes, blemishes of character are effaced, while virtues, till then potential merely, are seen in an unexpectedly vivid light.”11 And there were indeed some individuals from our scientific and medical communities who, during the current crisis, and despite open hostility from our country’s leaders, exhibited those crucial civic virtues that distinguish true men and women of action — they include but are not limited to Dr. Anthony Fauci, Dr. Deborah Birx, Dr. Robert Wachter, Dr. Peter Hotez, and Dr. Scott Gottlieb.

In thinking about the characteristics required of leaders during a crisis, Professor Bloch describes an individual from his wartime experience who embodied many of these good qualities: “Always ready to instruct and direct, he was the type of leader who knows how to leave to his subordinates that freedom of action which is so necessary if they are to carry out his orders effectively, though he never attempted to shuffle out of his ultimate responsibility for them.”12 He also notes that these superior qualities cannot just be handed down over time. One of the primary jobs of true leaders during a crisis is to inculcate a special sense of purpose in all members of frontline organizations.

One of the interesting and pleasant surprises during the COVID pandemic was to see the personal bravery of many mild-mannered men and women from the health professions. It was neither the blowhards nor the bullies who displayed the finest sense of honor during 2020, but often it was soft-spoken professionals who would not back down in the face of demagoguery. Professor Bloch describes this same behavior in the French military:

“It is a popular fallacy among officers that the man of hot temper, the adventurer or the hooligan, makes the best soldier. That is far from being the truth. I have always noticed that the brutal temperament is apt to break under the strain of prolonged danger.”13

During our own crisis, a lack of solidarity was displayed daily among our citizens during 2020, and this was a principal cause for our failure to combat the COVID threat effectively. One of the obstacles that prevents citizens from coming together in fighting a common cause is the natural fear of the unknown, like the fear that is caused by epidemics. Professor Bloch argues that regular soldiers can more easily confront known dangers as opposed to unknown dangers:

“Men are made so that they will face expected dangers in expected places a great deal more easily than the sudden appearance of deadly peril from behind a turn in the road which they have been led to suppose is perfectly safe.”14

Unfortunately, our long-term experience with epidemics in the United States was that they usually occurred far away, and that when they reached our shores, they often turned out to be less deadly or less communicable than anticipated. Professor Bloch acknowledges that French soldiers were often surprised by the rapid and unexpected actions of the German army: “They relied on action and on improvisation. We, on the other hand, believed in doing nothing and behaving as we always had behaved.”15 In the same way, many American citizens insisted on going about their affairs as if nothing had changed by openly refusing to wear masks, failing to maintain social distance, and continuing to attend large indoor gatherings despite repeated warnings from public health professionals about these behaviors.

Professor Bloch points out that many soldiers were surprised that their choice of careers would ultimately put them into harm’s way: “For the man who chooses the career of arms, personal courage is by far the most necessary of all professional virtues.”16 Similarly, our public health professionals should have understood that by choosing a career in the public health service, they would ultimately have to stand up to the forces of darkness by insisting on protecting the public’s health over advancing their own careers or convenience. It is sad, but not surprising, that some health professionals failed to stand up for science and public health during the current crisis. Professor Bloch noted that many French soldiers were not really prepared to bear arms for their country:

“[T]he habit does not always make the monk . . . in all countries and at all times there are men so lacking in imagination that they will choose an occupation without realizing what it involves. They will, for instance, elect to become soldiers without considering that, sooner or later, they may have to change the peaceful life of the garrison town for war.”17

Professor Bloch notes that esprit de corps is important in all military organizations. It is equally important for public health groups like the CDC, the NIH, and the FDA, and especially so during times of crisis: “What is needed is something more than a tradition handed down by seniors to juniors, by leaders to subordinates; it is an esprit de corps. This is particularly true in the case of military organizations.”18 It is sad to consider what additional useful actions might have been undertaken at an earlier stage by our remarkable public health and scientific organizations on behalf of the American people during the current crisis if they had simply been left to do their jobs in a professional manner and without undue interference by politicians.

The willingness to accept a level of incompetence within bureaucracies during peacetime became a major problem when a real crisis erupted within France: “Those bred up in army ways had, in the course of years spent in the bureaucratic machine, grown used to a certain amount of incompetence which rarely, if ever, ended tragically.”19 Ultimately, it is character that we must require and demand of our leaders and our citizens. Due to this lack of character during 2020, we saw similar painful displays of incompetence in our government that in ordinary times might have yielded only delays. In the current crisis, however, this lack of character resulted in thousands of unnecessary deaths.

Professor Bloch asserts that disagreements within a free country are the best sign of a democracy’s health and not an indication of decay. For this reason, we should welcome the opportunity to air our political differences in open elections with vigorous debate:

“It is a good thing, and a sign of health, that those in a free country who represent contrasted social theories should freely air their differences. Society today being what it is, class interests are bound to be at odds. Antagonisms there must be, and it is well that they should be recognized. It is only when this state of social friction ceases to be regarded as normal and legitimate that the country as a whole begins to suffer.”20

Perhaps foreseeing his own likely end, and also giving a dramatic expression of the ethical principle of justice (which can only be achieved with sacrifice), Professor Bloch offered a brief prayer for France that all free men should embrace:

“For there can be no salvation where there is not some sacrifice, and no national liberty in the fullest sense unless we have ourselves worked to bring it about.”21

In his closing remarks, Professor Bloch reminds us that during a crisis we should encourage bold spirits pursuing noble ends:

“A free people in pursuit of noble ends runs a double risk. But are soldiers on the field of battle to be warned against the spirit of adventure?”22

The Histoplasmosis Epidemic in Plattsburgh, NY: “A retrospective investigation of a Histoplasmosis epidemic in 1951 which had occurred 10 or 11 years earlier in Plattsburgh, N.Y. I saw a community react with mass panic and fright when the newspaper sensationalized the so-called ‘Pidgeon Fever Epidemic’ and inadvertently misrepresented the current dangers to the population of that community. I was fascinated by the assignment which I shared with Dr. Donald Fredrickson as participating in ‘medical detective’ work.”23 (From a questionnaire that my father filled out for a researcher from the University of Iowa’s History Department in 1984.)

The Poliomyelitis Epidemic in Essex County, NY: “[I had] the opportunity to enter the community and observe the effects of epidemics on the interpersonal relations of families, organizations, institutions, and the intrapsychic lives of individuals in such epidemics as the Poliomyelitis epidemic in Essex County, NY, in 1951-52.” (From a questionnaire that my father filled out for a researcher from the University of Iowa’s History Department in 1984. Also documented in the article titled “Poliomyelitis and the School Medical Officer.’24)

The Leptospirosis Epidemic in Roanoke, VA: “[I also had the opportunity to investigate] the Leptospirosis Canicola epidemic among workers in an abattoir in Roanoke, Virginia which gave me insight into the genesis of anxiety, panic, depression and its contagious nature.” (From a questionnaire that my father filled out for a researcher from the University of Iowa’s History Department in 1984.)

The Gamma Globulin Project for German Measles at Colgate University in NY: “The discussions I had with students at Colgate University whom we were “bleeding” to form a Gamma Globulin which we hoped would be specific for passive immunization for German Measles (as there was no vaccine at the time) gave me a premonition of the next student generation’s social and economic values, and an insight into what would become the great social upheavals on the campuses in the 60’s.” (From a questionnaire that my father filled out for a researcher from the University of Iowa’s History Department in 1984.)

Morbidity and mortality weekly report, Vol. 1, no. 3, January 25, 1952: Gastro-enteritis in NY: “Dr. M. Goodman, New York State Department of Health, has reported an outbreak of gastro-enteritis that occurred in a small group of women who made up a bowling party. It followed a meal in which all were said to have eaten shrimp cocktail and ham. Dr. Goodman also reported that 1 of 3 newborn infants who were ill in an institution had a positive stool culture for an organism of the Salmonella group. All had onset of illness on the same day.”

Morbidity and mortality weekly report, Vol. 1, no. 10, March 14, 1952: Influenza in Millerton, NY: “Dr. Melvin B. Goodman, New York State Department of Health, reports an outbreak of influenza-like disease occurring in Millerton. The disease had its beginning around February 10 and reached Its peak in about 1 week. It was mild in nature and affected both adults and children. One hundred and thirty-eight out of the Millerton school population of 425 were absent on February 19, presumably from this disease. Dr. Goodman also reports that a house-to-house survey in Glens Falls showed that about 25 percent of the Glens Falls population have had an influenza-like disease since February 12. Throat washings and blood specimens were obtained from 2 patients. Laboratory results are not yet available.”

Morbidity and mortality weekly report, Vol. 1, no. 14, April 14, 1952: Shigellosis in NY: “Dr. M. Goodman, New York State Department of Health, has reported an outbreak of bacillary dysentery which occurred in an Institution. In a group of 250 children, 46 developed an illness characterized by acute onset with fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Stools contained mucous and blood. The initial case appeared on January 22 and in a 2-year-old child. Single cases developed thereafter at irregular intervals of 1 to 7 days. A total of 10 cases had occurred by February 8, and 25 cases were observed in the next 2 weeks. A tapering off then began, and 11 cases developed between February 21 and March 2. All parts of the institution were involved in the outbreak. Person-to-person contact is regarded as the mode of spread of infection. Shigella sonnei type of organisms were recovered from the stools of patients.”

A Study of Developmental Disabilities: Melvin Goodman et al., A Prevalence Study of Mental Retardation in a Metropolitan Area, 46 Am. J. Public Health 691, 702–07 (1956):

“The 1955 Onondaga County study in New York State [the original name for this study] remains as one of the mile-stones in the development of mental retardation prevalence methodologies. The study attempted to identify the retarded up to age 18 years using criteria applied by child-care and other agencies operating at the community level. This technique, in effect, implied the rejection of criteria which were independent of the then current practices in the community. It emphasized the level at which individuals function in their home environment. It was a broad and somewhat flexible approach to the identification of the mentally retarded. Agencies throughout the area were requested to designate persons who could either be definitely identified as mentally retarded or suspected of mental retardation. Identification was on the basis of developmental history, I.Q. score, or poor social adaptation in comparison to age peers. While the procedures of the Onondaga study tended to yield rates somewhat higher than previous studies, it did identify a population which was termed retarded by responsible practitioners and which they believed was in need of more adequate services. None of the identified persons were interviewed by the research team with the result that only minimal information was available in many instances. Psychometric and other data, when available, were often scores from differing tests and were not directly comparable.” C.W. Portal-Foster, Community Diagnosis: Mental Retardation and Social Science, 62 Canadian J. Public Health 1, 46–53 (1971).

Justice Gordon Goodman serves on the First Texas Court of Appeals. He is a member of the Texas State and Pennsylvania Bar associations, and he lives in Houston, TX.

HPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit HPHR’s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email communications@bcph.org for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of HPHR Journal.![]()